The anything-can-be-called-art-these-days outlook is the cardinal cliche of philistinism. Yet it is also undeniably something which everyone, especially those whose job it is to engage with contemporary art, will have thought about something they have seen. The twentieth century saw an arms race of radicalism in art that, with the turn of the modern to contemporary eras, isn’t showing any signs of dying down, and it can sometimes be hard to keep up with the thought behind new movements. Simon Morley formulated his ideas about approaching challenging art “over a period of about fifteen years [in which he] talked about art, old and new, to almost anyone who wanted to listen”, as a lecturer, visual artist and museum guide.

The result is his book Seven Keys to Modern Art, which, “rather than proceeding on the basis of the familiar art movements or ‘-isms’”, approaches twenty famous works made between the turn of the twentieth century and the present day by looking at different “keys” to understanding them. They include the “historical”, “biographical”, “aethstetic”, “experiential”, “theoretical”, “market” and “sceptical”.

“The twentieth century saw an arms race of radicalism in art that, with the turn of the modern to contemporary eras, isn’t showing any signs of dying down”

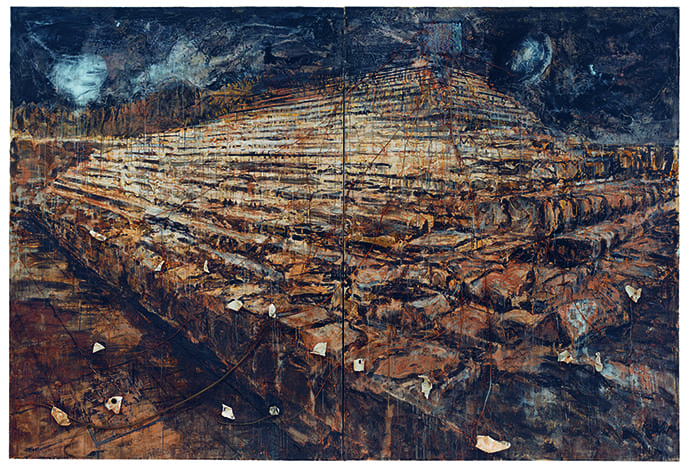

The biographical key, for instance, approaches works by Andy Warhol, Louise Bourgeois and Anselm Kiefer in terms of how they relate to their author’s life; the historical key defines works in the context of their day, age and place; the theoretical, in terms of the movements or “-isms” behind it. The market key outlines the work’s history of purchase and the prices that similar works by its artist usually command, as well as how its value affects the viewing experience or speaks for its quality, etc.

Anselm Kiefer, Osiris und Isis (Osiris and Isis), 1985-1987

For the most part this is a fresh, systematic way of dealing with important art, ostensibly for people who might find it difficult in the first place to isolate the factors that make potentially impenetrable works important to the people who venerate them. It is useful to have all of these things in the same place for specific works. Morley offers crash courses in important landmarks and figures. Malevich’s Black Square, Rothko’s Abstract Expressionism, Land Art and Pop Art have their essential tenets laid out. “Cubist works [like Picasso’s Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper (1913)],” for instance, “launch an assault not only on the integrity of the image itself, but also on conventional notions of the artist’s skill”.

“Its register risks alienating the ‘lay’ reader, if there is such a thing”

Saying that, its register risks alienating the “lay” reader, if there is such a thing. Morley often writes like this, even before he’s actually brought in any concrete examples: “Preference is given to the equivalent or complementary relation as opposed to the binary, contrary or oppositional”; “The keys are part of a web of processes in which opposites penetrate, are relational, and in a state of dynamic becoming.” This is not just the language of academia, but of blurbs and labels on museum walls that Morley himself admits can mystify contemporary art instead of glorify it. If I was new to the game, this might be exactly the sort of thing I’d be hoping to escape, or at least have minimized for me. And for those who don’t need overviews of Cubism or Duchamp or Surrealism, the book is quite rudimentary in its content. Because of this, it’s quite difficult to picture who the book’s ideal reader is supposed to be.

When the keys are applied, there are recurring problems. The “experiential key”—which roughly describes what a work feels like to be in the presence of—is very similar to, or sometimes the mere extension of, the “aesthetic key”—which roughly describes how the work appears to the eye. In a chapter about Francis Bacon’s first Screaming Pope, one key (aesthetic) is devoted to talking about the picture plane, and the other (experiential) about the brush strokes. In the Frida Kahlo chapter, one (experiential) discusses how she depicts herself and paints song lyrics onto the work, the other (aesthetic) how the discussed painting has the “aura” of a religious icon. The two keys are not only used interchangeably, but sometimes swap round. (You’d imagine, for instance, that the “aura” produced by a painting is on the experiential side of Morley’s own terms.)

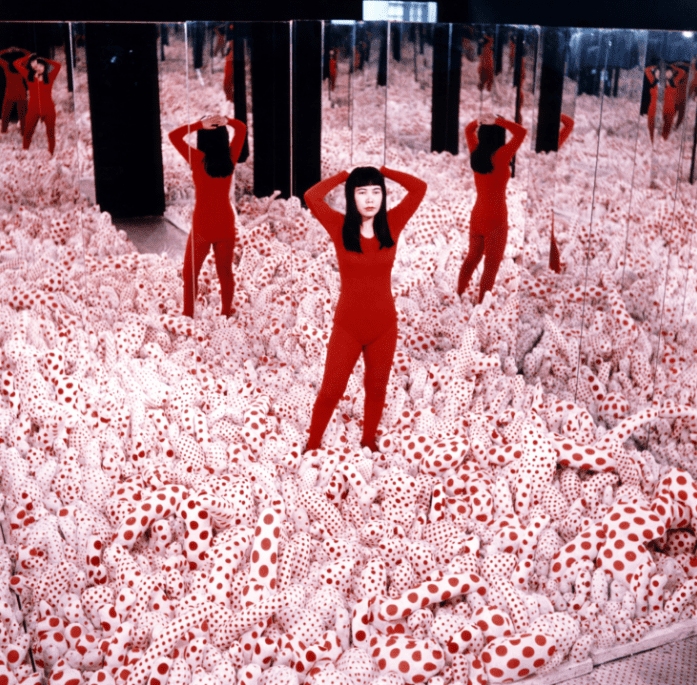

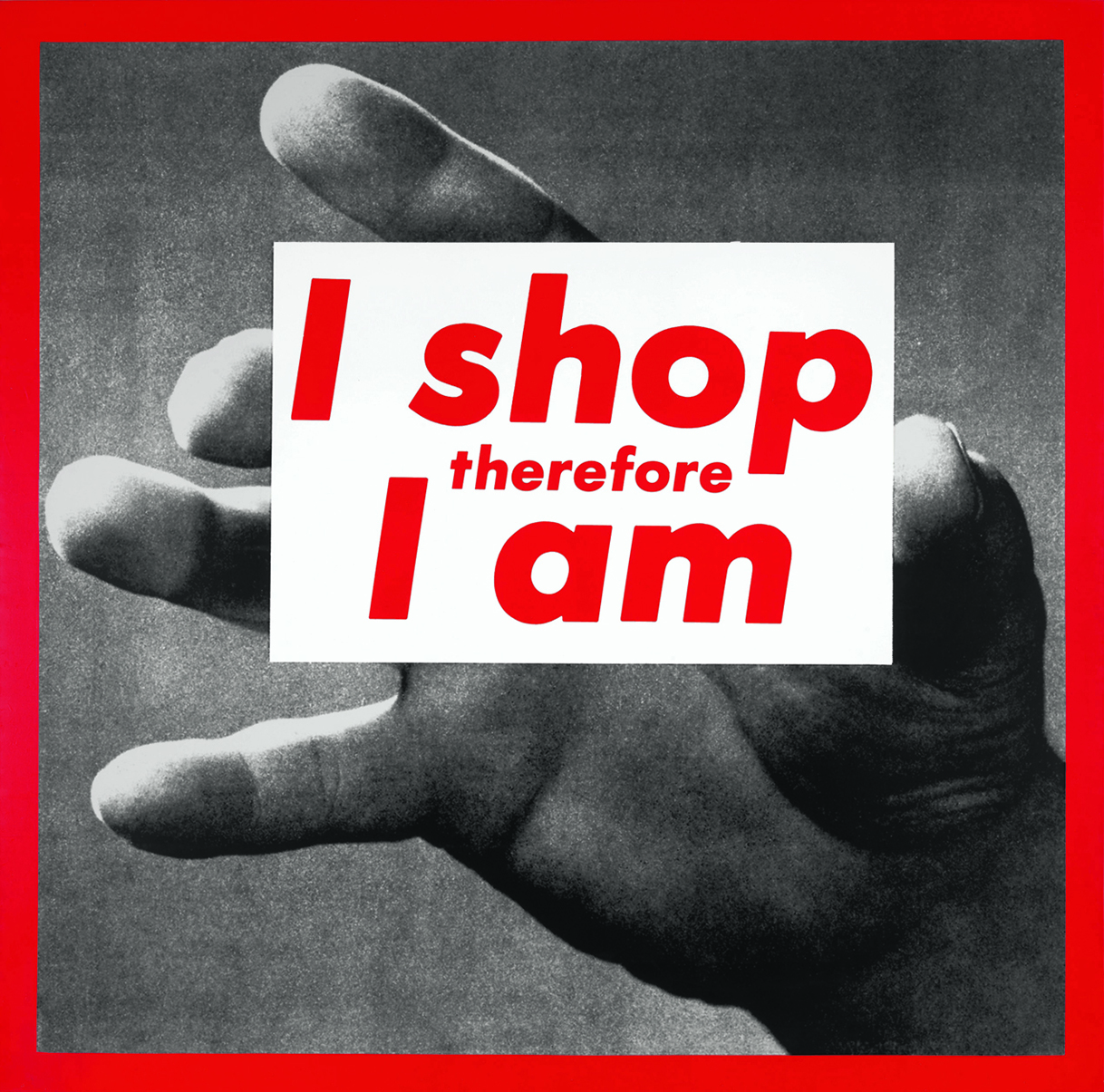

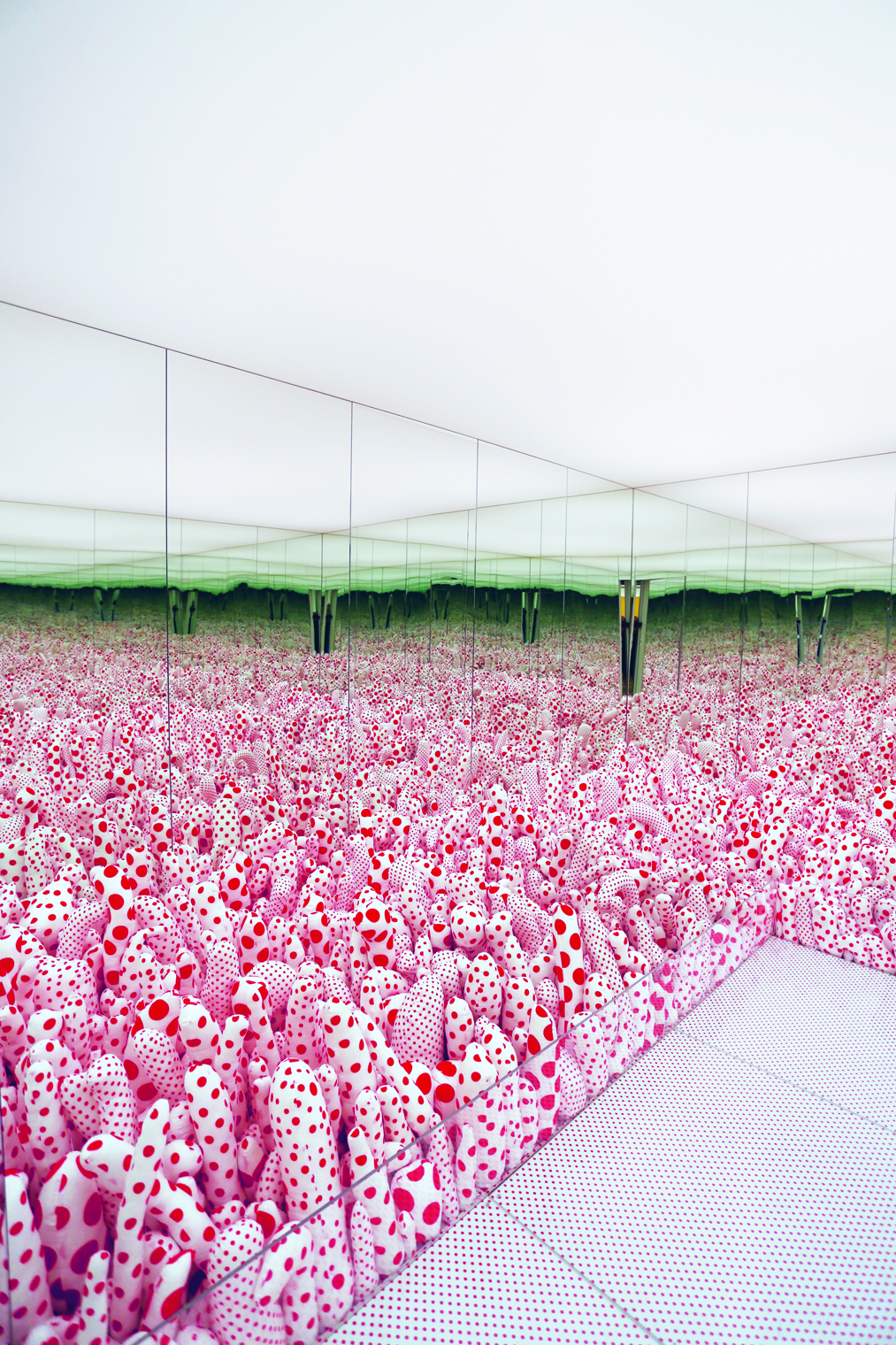

It is also dismaying that in every chapter about female artists (Kahlo, Louise Bourgeois, Barbara Kruger and Doris Salcedo) except one (Yayoi Kusama), Morley begins with the biographical key, therefore affording this approach the most weight of his seven. Sometimes this is absolutely necessary (Bourgeois, Kahlo at a push); sometimes it seems tone deaf to the artist’s concerns. Especially in the case of Kruger’s work, which is political and feminist but, Morley argues, impersonal. Or that of Salcedo, who Morley discusses in his opening biographical paragraph: “Salcedo isn’t interested in recounting the history of Colombian or any other specific case of violence, nor in narrating a single story—least of all her own.[…] Her interest lies in the universal face of violence.”

Neither the chapter on Joseph Beuys—which is about a work made of felt and fat which is directly influenced by the artist’s personal experience of those substances—nor the chapter on a work by Bill Viola—depicting a man submerged in water, which responds to a childhood experience of being submerged in water—begin with the biographical key. Only four of the fifteen works by men here are introduced via the biographical key, while four of the five by female artists are.

The most valuable of Morley’s keys turns out to be the “sceptical key”, which challenges the received “consensus” and “cultural credentials” of each of the twenty works set out by the six previous keys. Here he is on the Picasso: “He used the materials that surrounded him, and this can suggest that, at least in principle, anybody could have made the collage, so it challenges the idea that a work of art should show evidence of training and technical skill.” (The rub here, of course, being that it took training and skill to conterpose the textures of the work, and deep knowledge of art to consider setting it up against previously created art.)

He questions whether Barbara Kruger’s use of advertising imagery gives “advertisers additional leverage through which the viewer/consumer can be more successfully lured […] symbolic gestures that are soon reabsorbed into the system they are intended to oppose.” He questions the “very lack of usefulness” of Matisse’s Red Studio, and whether the artist should have strived to mean more with his art. Whether he wasn’t aiming high enough. On Lee Ufan and, by extension, the perceived simplicity of South Korean Dansaekhwa painting, he says: “Lee considers it necessary to write about his practice in order to give it meaning. […] while his work trades on the look of spontaneity, it is actually highly premeditated and conceptual.”

Seven Keys to Modern Art is at its most useful when it argues with itself, and becomes a collection of contrapuntal, polyphonic responses to specific canonical works of art. Doing this—questioning what is worthy of being called art, through an ever-growing and inclusive list of criteria—is the only way of establishing the beauty or power of difficult works, and showing their brilliance to those who those who haven’t seen.