An artist recently told me to be happy and curious about things I do not understand. It could be an opening to a new territory in the arts. This advice took me on the train to Hamburg, to see a show by Oslo-based artist Ida Ekblad.

I had seen some of Ekblad’s paintings some years ago in Berlin and it seemed to come from a source that I did not understand. There was a kind of casualness, sometimes even sloppiness, to her paintings, as if the artist did not want to lose too much time making them. Should I take them as serious paintings? The formats were huge, which did not make it look accidental. It clearly wanted to be art.

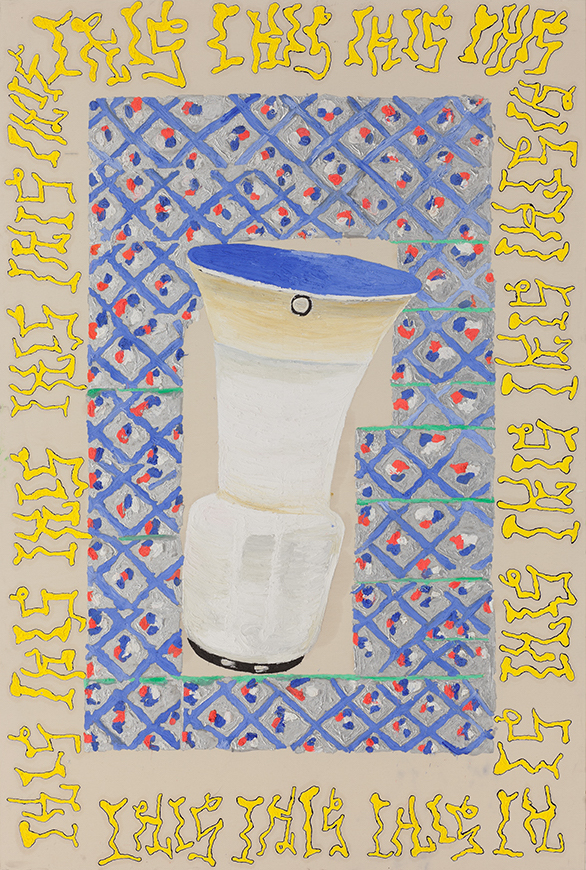

As I saw there was an institutional solo show in the Kunsthaus Hamburg of Ekblad’s work, I took the train. It would certainly offer an opportunity to get a better look at the work, and the intentions of the artist. The Kunsthaus had reserved the whole spacious white hall for Diary of a Madam, as the show was called. I found one of the casual kinds of painting I had seen in Berlin, which repeated a tag-like signature in different sizes over the canvas. Interestingly enough this painting was the exception in a row of seven paintings that were presented like a frieze, without any space between the individual paintings. While the middle painting had no clear figurative motif, just the tags, the other six had: in each of them a vase was depicted, as a centre of attention. An extravagant vase, a floating vase, a vase against a background of colour patches, a vase looking like an organism and so on.

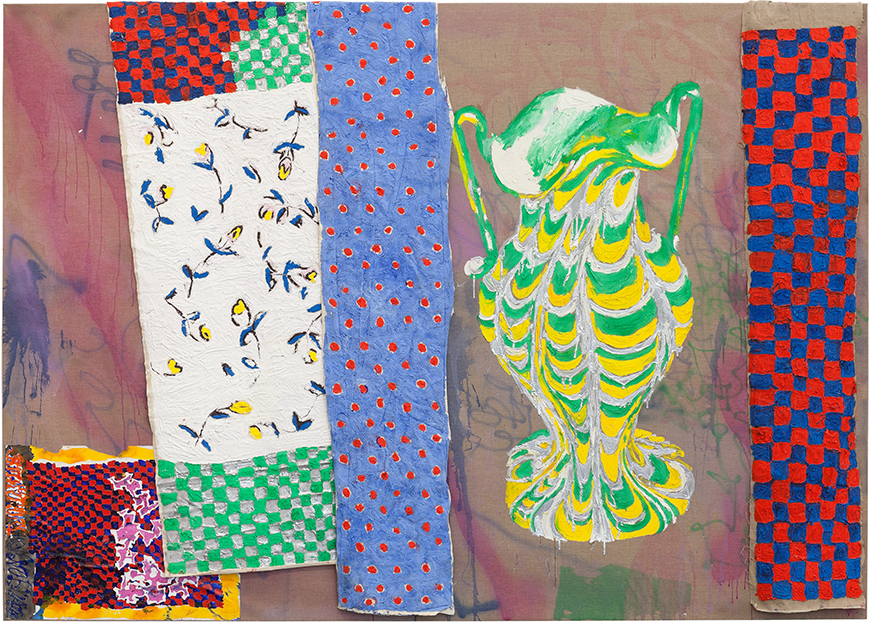

The director of the Kunsthaus had joined me to look at the paintings. They were inspired by a trip Ekblad made to Venice at an early age, she told me, and a remembered first encounter with Murano glass. This explained some of the colourful display and voluptuous forms. Vases, the director reflected, can be seen as symbolizing fertility and life, but they can also be associated with death, as they can contain the ashes of a deceased one. This she considered to be two sides of Ekblad’s attitude. Not only the cheerful but also a darker, Nordic mood was involved here. I looked closer at the way Ekblad was depicting her vases. To me they did not look like death, rather like celebrations of life, colourful, vibrant, maybe with some melancholy in their isolated appearance. The way they were painted, with thick “puff” paint, made a contrast with more flat backgrounds, sprayed with an airbrush. The paintings seemed to have one leg in art history, in a serious classic way of painting, and another leg in a more sloppy, street kind of painting.

On the opposite side of the exhibition hall, there were more paintings with vases; some of them had pieces of painted fabric added on. They were interrupted by copies of a single poster, showing the photographic portrait of a child, her mouth open, showing teeth she was still missing at her age. Under the image, was the artist’s name, designed as if it was an ad: EKBLAD. So this was the artist as a child, looking at us? No, the director said. Ekblad was apparently suggesting things, to confuse the viewer about the identity of the maker. Just as the title, Diary of a Madam, did not have a clear anchor point in the show.

Once, on a trip to Oslo, I actually met with Ida Ekblad. As she had to leave for the airport, while I was just arriving in town, we agreed to meet in a cafe in the centre. There was no time to see her studio and look at her works. What I remember is that she came with a suitcase, a small woman with a big suitcase on wheels. In Hamburg, I found a similar suitcase in the exhibition, this time without the presence of the artist. It was opened and there were some sculpted figures inside, and around it on the floor. It looked like it had been opened violently; some splatters of colours were on the ground. The director told me they were the remnants of a performance that had taken place. A singer had used Ekblad’s suitcase, and the artist had decided to leave the traces, as another ingredient of the exhibition.

This renewed encounter with Ekblad’s work left some new gaps in terms of understanding. But in this case, the question marks were counterbalanced by a clear motif, the vase. Especially the way the artist got physical, through the thick application of paint, and through including extra pieces of fabric, made me want to engage with the work. The traces of the performance on the floor, two additional metal sculptures, and the repeated poster of ‘not Ida’, all this together created a framework to look in a different way at her paintings. The casualness, as I saw it now, just like the identity ‘ads’ and tags, created the noise and confusion which was needed to put the vases into clear focus.

‘Ida Ekblad: Diary of a Madam’ is showing at Kunsthaus Hamburg until 23 March. kunsthaushamburg.de

Detail of: Ida Ekblad, Let me not forget to record, do not to disturb if death should happen in the night. Not to let me know it until I arise at my usual time, 2017, c-print on paper, airbrush and 3d puff paint on linen, ca. 2 x 18 m, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris, photo: Hayo Heye, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Ida Ekblad, installation view, Diary of a Madam, Kunsthaus Hamburg 2017, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris, photo: Hayo Heye, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017