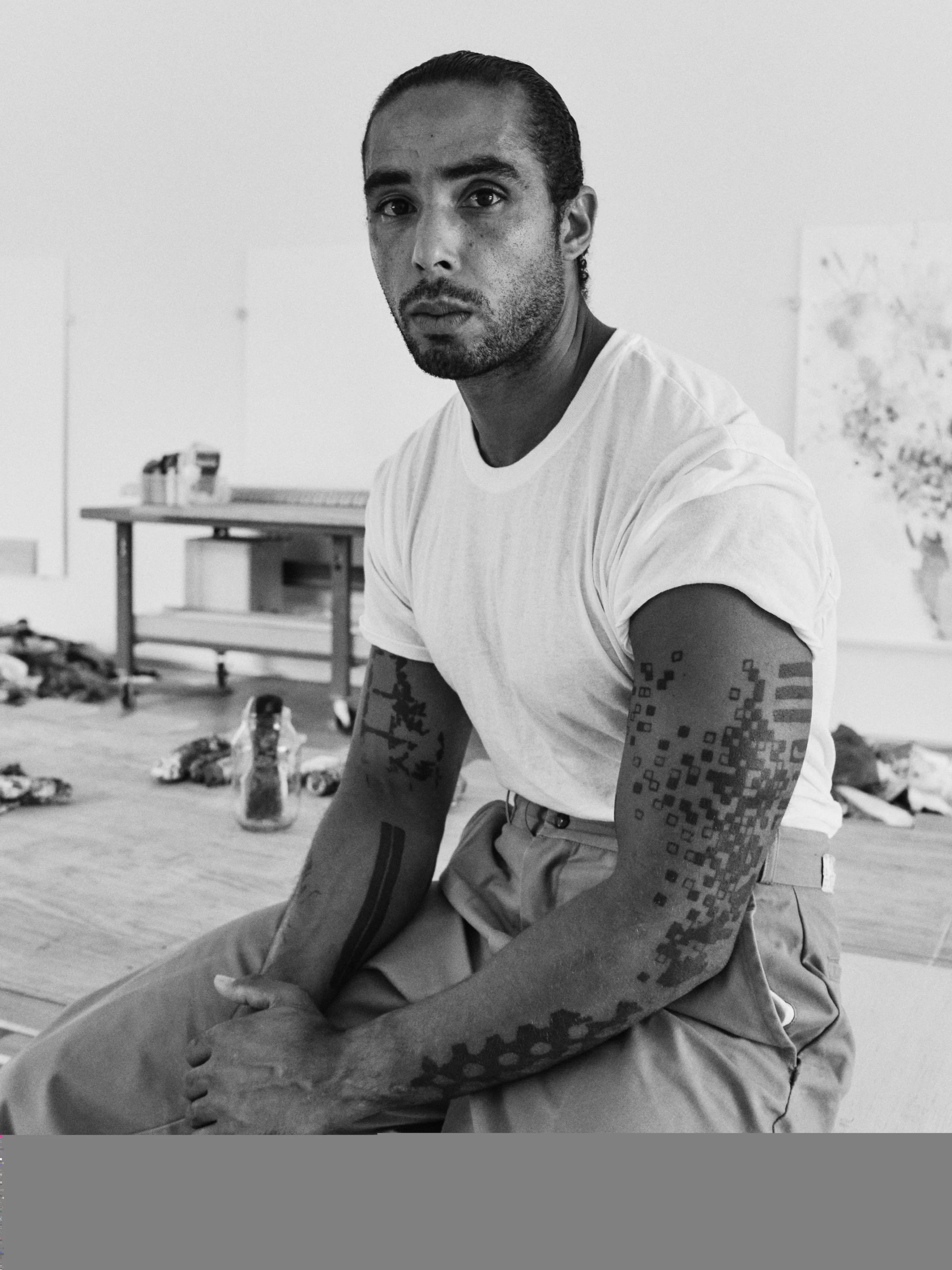

Writer Folasade Ologundudu speaks to artist Hugo McCloud about vulnerability, loss, and identity, specifically highlighting the ways in which these things have influenced his art.

FO: The vulnerability in your work is pronounced in your use of material, subject matter, and your openness to share your lived experiences. Talk to me about the vulnerability in your work and how, in your opinion, does this make you a better artist?

HM: In some ways I’ve always been vulnerable. What’s different now is I’m learning to embrace the vulnerability and use it as power instead of a weakness. I feel there’s more power in being open and honest about that than defending it. My work is about a continual investigation. I’m continually putting myself in a spaces of newness because I feel comfortable in that vulnerability.

FO: You’ve been frank about the recent personal loss you’ve experienced in your life due to the passing of your close friend Netic to an armed robbery in Mexico. How has this loss impacted your work, your consciousness, and your pursuit of creativity?

HM: For the first time in my life, I walk around with a bit more fear and uncomfortability in certain situations. We’re exposed to so many atrocities through TV and our phones, but when you see it face to face, it’s completely different. My first response after everything settled was to jump immediately back into work. I unconsciously knew that my work was a place I could put feelings I didn’t fully understand. I needed to find beauty within my own struggle. Through therapy, I realized I was drawn to certain individuals because of the way that I looked at myself. I’ve dealt with the trauma of my experiences of Mexico and losing my friend in an interesting way, doing what I felt I needed to do. I’m also very much currently dealing with the reality of the loss—not just the loss of my friend, but the loss of my actual home, where I saw myself living. I’m definitely not in the space I envisioned. For lack of better words, I am displaced from the place I called home, from what I invested in, and where my belongings are. I’m very much still dealing with those pressures and anxieties and I’m trying to avoid masking it so I can figure out what the next moves are.

FO: One of the things that’s glaringly obvious is the fact that you’re rarely described as a Black artist but you’ve described yourself that way. You’ve mentioned being inspired by Mark Bradford, and, in thinking about you and your work, I’ve been thinking about Jack Whitten and the way he pushed boundaries with materials and tools, as well as Jackson Pollock, and the ways in which artists of different backgrounds contended with the movement and the societal constraints and/or freedoms they felt that abstraction offered them. Can you speak about the freedom that abstraction has offered you, if any?

HM: I’ve made a choice not to engage in personally defining myself as a Black artist or an abstract or figurative or whatever you want to call artist. I feel that personally defining any of those things puts me in a category of needing to have a reason to do what I’m doing. My question is, why do Black artists always have to be defined?

When I think about the time before American slavery and the richness of Africa, if you thought about a craftsman or artist, was what they made tied to race or were they able to just be free in their creation? I like to engage in my work from that space. If I’m painting flowers, I’m still painting flowers as a Black man. I’m still getting my hair braided by the Senegalese. I’m still eating barbecue chicken. I’m still listening to the Drake Kendrick battle.

In the sense of abstraction being freeing, I remember doing a talk with Jack Whitten, and him saying, “I made these things because it was what I liked, it had nothing to do with the narrative,” and I think that’s important for Black people and people of color to hear it’s okay to do that.

FO: Tell me about some of the places that you’ve traveled to, the moments that have stayed with you. You can recall specific moments or describe general feelings.

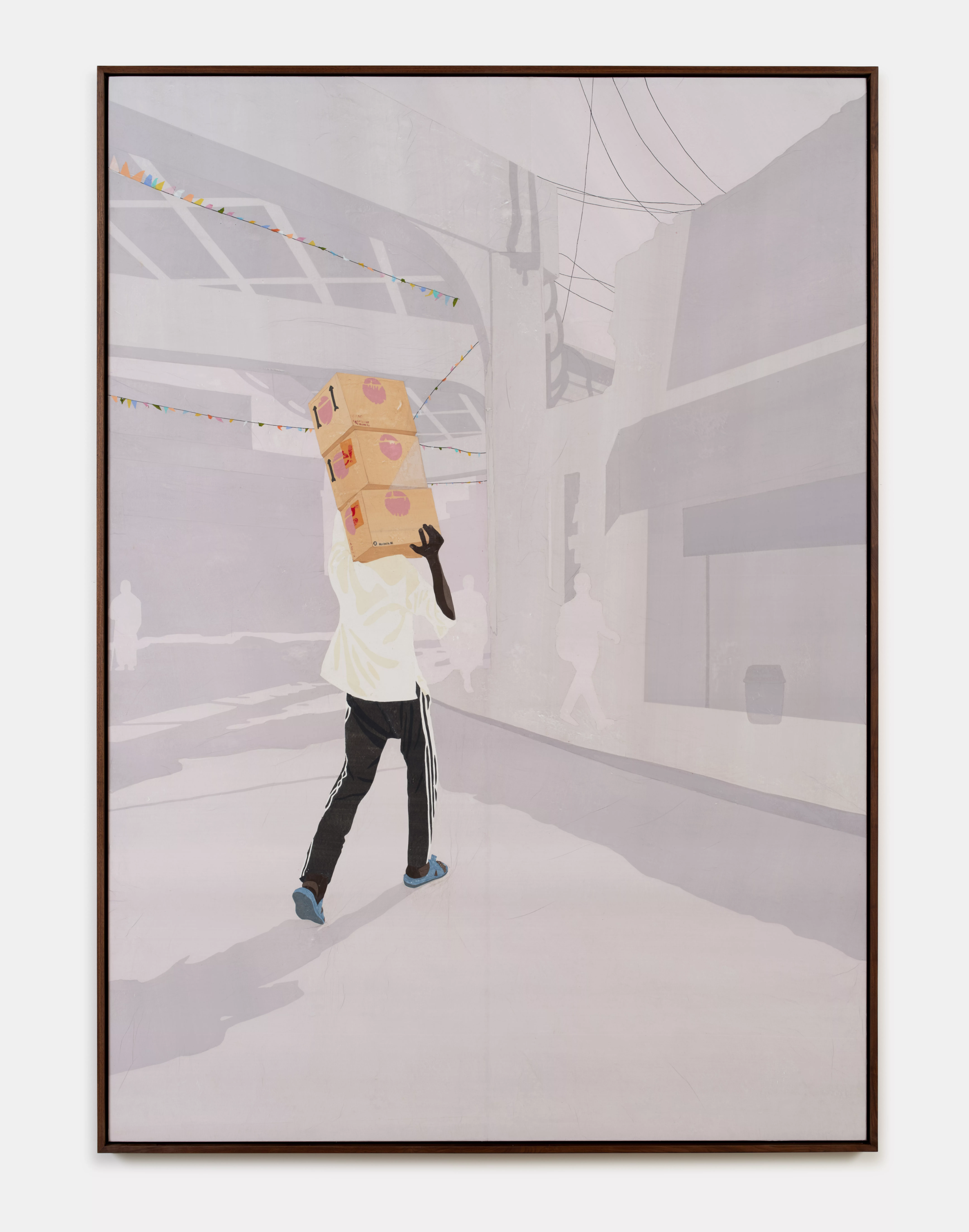

HM: There was a huge block of time that I wanted to travel to environments that were somewhat ‘sketchy.’ I felt those areas were where you’d see the real richness of a culture and the richness of textures and materials. When I traveled to places like India, Africa, Latin America, and certain islands, when you go to these environments, you see the connection that the ghettos in India are very similar to ghettos in Africa or Asia. I also find it relatable because I was struggling in those times. It was familiar. When you’re an up and coming artist in West Oakland and dealing with literally being robbed by crackheads and having to chase them down the street for your tools and then being in Bushwick in 2009, these are not the most enjoyable environments to visually take in.

It was also really interesting for me as an artist because when I first went to Soweto and Johannesburg, the people I went to there with were my good friends, they were graduates from Cornell and one of their classmates was the granddaughter of the Mandela’s. So those are the people that took us around but there was also this very opposite side of the world, where we’re in Soweto one day and then we’re literally at a barbecue with Winnie Mandela in a regular house the next day. It’s the same thing when I’m in the Philippines. The people hosting me are very affluent and want nothing to do with the ghettos. At the same time, my research and my studies are in those ghettos.

FO: You’ve included flowers in As for Now. I want to talk about the juxtaposition between the beauty of impermanence and the idea of something that will last forever. Can you speak about the juxtaposition of depicting something incredibly impermanent, such as flowers, but made with plastic, a substance that never biodegrades, and bears a sense of permanence? How do you consider these opposites?

HM: I don’t approach the flowers from that place. I approach the flowers from a space of creating something I saw as a youth growing up in my family’s house and finding my own value in it. My uncle-in-law was a famous painter in Europe, who did a lot of still life paintings. Growing up there was always this underlying sense that the work my father and Black side of my family did was not real art because they weren’t famous and their work wasn’t valued in the same way. There was this judgment of my father and his siblings that downplayed them like they were no good. So I think reapproaching that idea comes from one, my appreciation of what I saw from my mother being a florist and having a design studio and being around that my whole life. Then there was also indirectly having this conversation with my family saying, we make valuable art too. I am half European and I’m half Black—I paint flowers too and they’re valuable and they’re worth something. It’s my way of creating the same things they were creating and things that are valued in museums. All of my work is some form of constructing. I don’t want to just paint a flower. With the materials, the flowers with plastic, it’s like building. Then I’m painting and that becomes the delicate part, but the rest of it is building, it’s constructing, which ties into who I am as a creator.

FO: What is on your playlist right now? What music are you listening to and what is inspiring you in this moment of your life?

HM: For the last year I’ve listened to very little music. I’ve been listening to more podcasts, news, and history. When I’m in a studio, the music I listen to is usually some type of electronic music, without words. The reason why is because I grew up in jazz. My mother and father had a jazz club and it used to be my main music. I don’t listen to jazz that much at all lately. But music changes your mood, right? There’s something about electronic music that is repetitive, somewhat similar to the stamp paintings or to the process of the plastic work. It’s continual, one thing, one train of thought, one feeling.

I think the reality is, although I’m grateful and I feel like I’m showing my gratitude by committing to the work, to be honest, I do feel away from home, away from the environment that I created for myself that I called home. It’s a really interesting feeling to feel that, but not be struggling.

FO: Because you associate that with struggling?

HM: No, because when you’re struggling in a type of way, you’re not fully focused on your emotions. You’re focused on taking care of business and being able to survive. That’s the difference, and I’ve been there for years. I was there for 10 years trying to make it in the art world, trying to figure out how to pay rent for three months. So when you’re not in that position, but you’re dealing with certain mental aspects of it, it’s an interesting dialogue.

On the one hand, you’re fortunate and you’re grateful and that’s why you’re pushing forward. On the other hand, you’re in this space where you feel—I don’t know—I just feel unsettled. As I’m doing therapy, I’m seeing the relationships with myself and even communicating that to you is me learning to be a hundred percent truthful with myself and I feel as an artist as well, it’s important that we communicate these things openly because I feel like it’s a lot of things and feelings that a lot of people are dealing with and I think that when you try to act like you’re not dealing with that…I’m not with that.

Words by Folasade Ologundudu