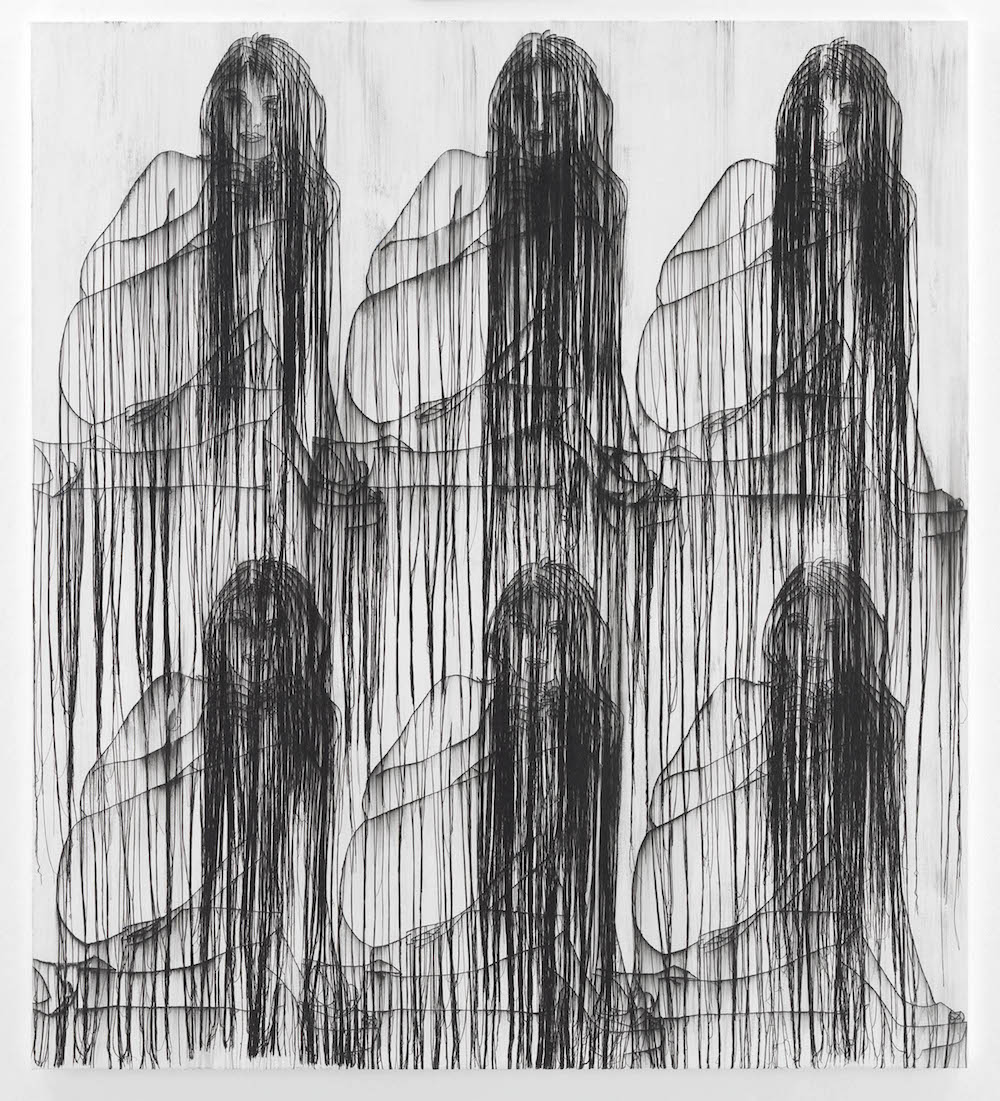

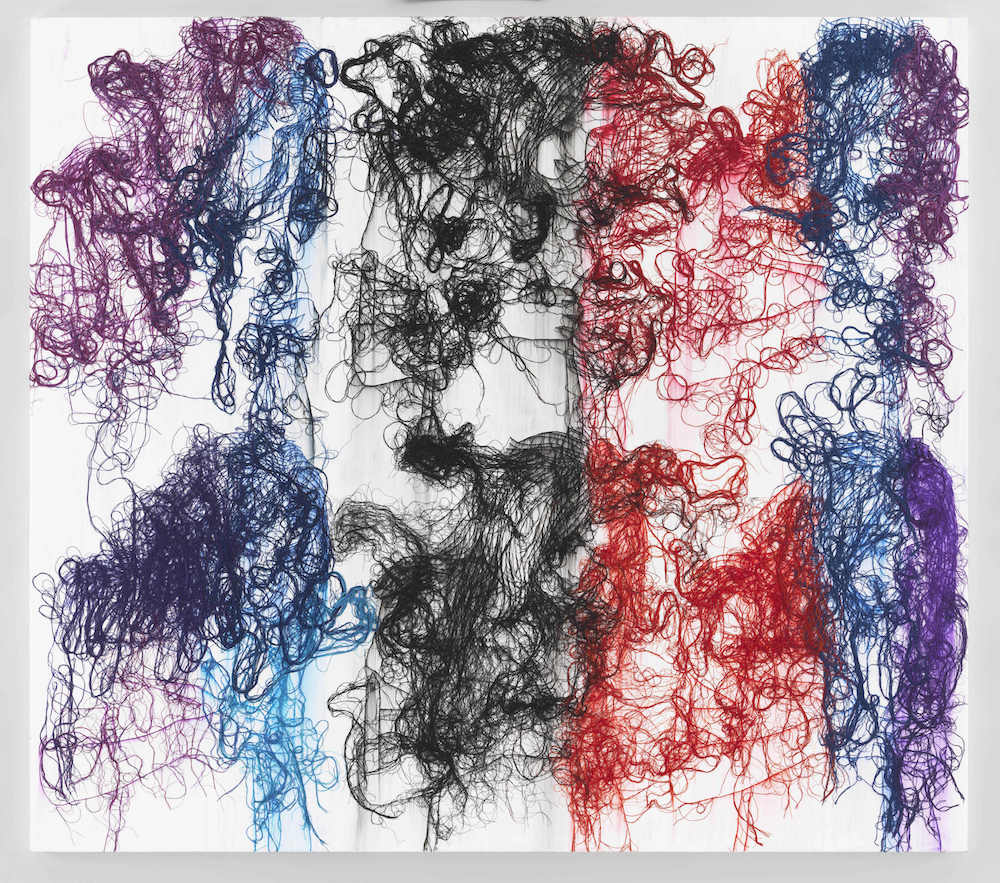

Images of suggestively-posed white women looted from men’s porn magazines are the starting point for Ghada Amer’s embroidery paintings on canvas. Needle and thread, traditionally considered women’s craft, reclaims the two-dimensional from the male-dominated history of painting.

Amer and I first spoke in a Dubai hotel lobby two years ago, just before her show Earth. Love. Fire. opened at Leila Heller’s 15,000 square foot Alserkal Avenue showplace, marking a return to the Arab world after more than two decades. Our voices were drowned out by drab brown birds gossiping in the pink bougainvillea beyond our table. Although the Heller exhibition did hint at Amer’s erotic figures (and marked the first viewing of a new medium for the artist’s ceramics, which were the product of a residency at New York’s Greenwich House Pottery) there was a degree of self-censorship at play. There were topics demanding discussion that would not be printed by any regional publication. We agreed to meet again.

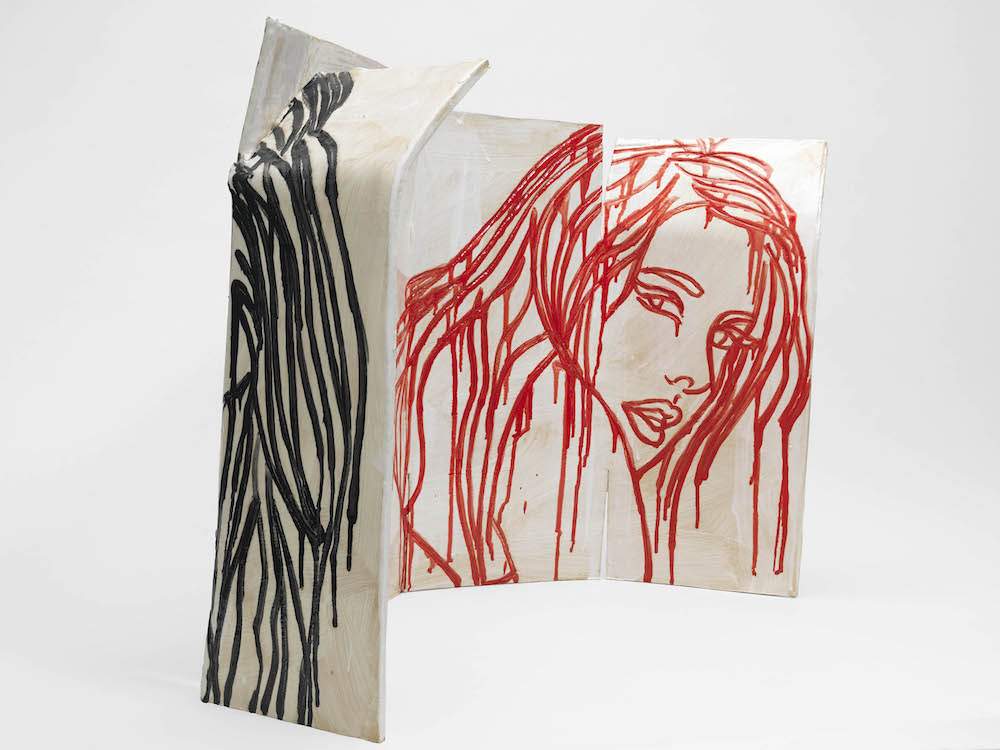

Amer and I reconnected in the US as she prepared for an untitled solo show at Cheim & Read in New York, set to open 5 April, presenting a new body of paintings and ceramic sculptures that feel like a shrewdly-honed continuation. Amer shares a cluttered studio with Reza Farkhondeh, who she met while still a student at the Villa Arson in Nice, France and with whom she often collaborates. They are in the midst of renovating a new space in Harlem. Our conversation begins where we left off, dissecting the unexpected sense of freedom Amer experiences whenever she experiments with ceramics.

You are right-handed and yet often force yourself to sculpt with your left. Why?

I began the left-handed sculptures when I started making ceramics in 2014. I was almost like a young child, suddenly realizing I have a left hand. I was noticing what the left hand could form. It was like surrealism, to see what it made on its own.

The thing that interests me here is your indifference to the threat of failure. You are unafraid to start at the beginning, experiment and even fall flat on your face in the studio.

I have always loved children’s drawings. I relate to children’s fearlessness. They don’t care what people are thinking because they are creating and at the same time discovering. This is how I feel in the ceramics studio. My ceramics are like my paintings, but without the thread. Except with the paintings, I always think about the father figure and the male, and all the paintings previously done by men.

When you paint you have the whole weight of the history of painting on your shoulders, but with ceramics do you feel there is not such legacy of male dominance?

It’s freer for me. I sew on the paintings but I don’t like to sew. I want to show that women have been suppressed. Sewing helps me to articulate this problem.

The erotic figures have been in your practice from the beginning. How did they first come to you and why have you continued with them for so long?

I’ve always loved to draw nudes, particularly of the female body. Probably because of my education and all the frustrations of growing up in France and being from a Middle Eastern family, there were a lot of problems and questions about sexuality and the body that I had when I began. These are almost all self-portraits. They are all the same female body. My body. Your body. It doesn’t matter. Drawing the body began as representation but has become more of a repeating motif for me, so to speak.

Hair is an ongoing theme, especially in Glimpse into a New Painting. To me it looks like pubic hair which is meant to protect the body against invasion from intruders, either of the human or disease variety.

I posted this piece on Instagram and someone commented to say it was very hairy. I replied no, it’s very painterly. I don’t see the hair.

You’ve done two recent paintings that seem to call out the default mode for beauty, White Girls, and one you’ve titled White-RFGA, as it’s a collaboration with Reza. It’s usually impossible to deduce the skin colour of the figures you embroider. Why have you decided to label them so clearly here?

My girls are always white and blonde.

All of them?

Maybe not all of them are blonde, but certainly all of them are white. The cliché of beauty in society is the white woman. It’s not the black woman, the Middle Eastern woman, or the Asian woman. There is porn featuring older women, but it’s not the mainstream. You can’t have a fantasy for all women. Either you like black women, fat women, women with big boobs or something else. It’s all fantasy—desire without emotion—and the mainstream is white.

You’ve wished aloud before to live life as a white male British artist. If you had the same body of work, how do you suppose it would be received differently with that identity?

I may be from the Middle East, but I’m actually from nowhere. I grew up in France and I live in the US now. Everyone wants to push you aside to make you the other. They don’t want to include you in the history of art.

Courtesy of the artist and Cheim & Read, New York