Standing in a vast warehouse in an industrial park just outside Wakefield, in the north of England, designer Adam Wadey is flicking through video clips of Olympic gymnasts performing floor routines, their bodies twisting across the screen of a dusty MacBook Pro. Forklifts screech and drills whirr in the adjacent hangars, where a company constructs stage sets for bands such as Muse and The xx, as well as the London Design Biennale.

Wadey continues through the digital slides, presenting edited videos of sprinters, swimmers and pole vaulters, alongside infographics showing the distribution of Olympic medals by country for the 2016 games. He is the lead designer of The Constant Gardeners, a new art installation by Jason Bruges Studio for Tokyo Tokyo Festival Special 13, the cultural showcase running alongside the rescheduled Olympic and Paralympic games this summer.

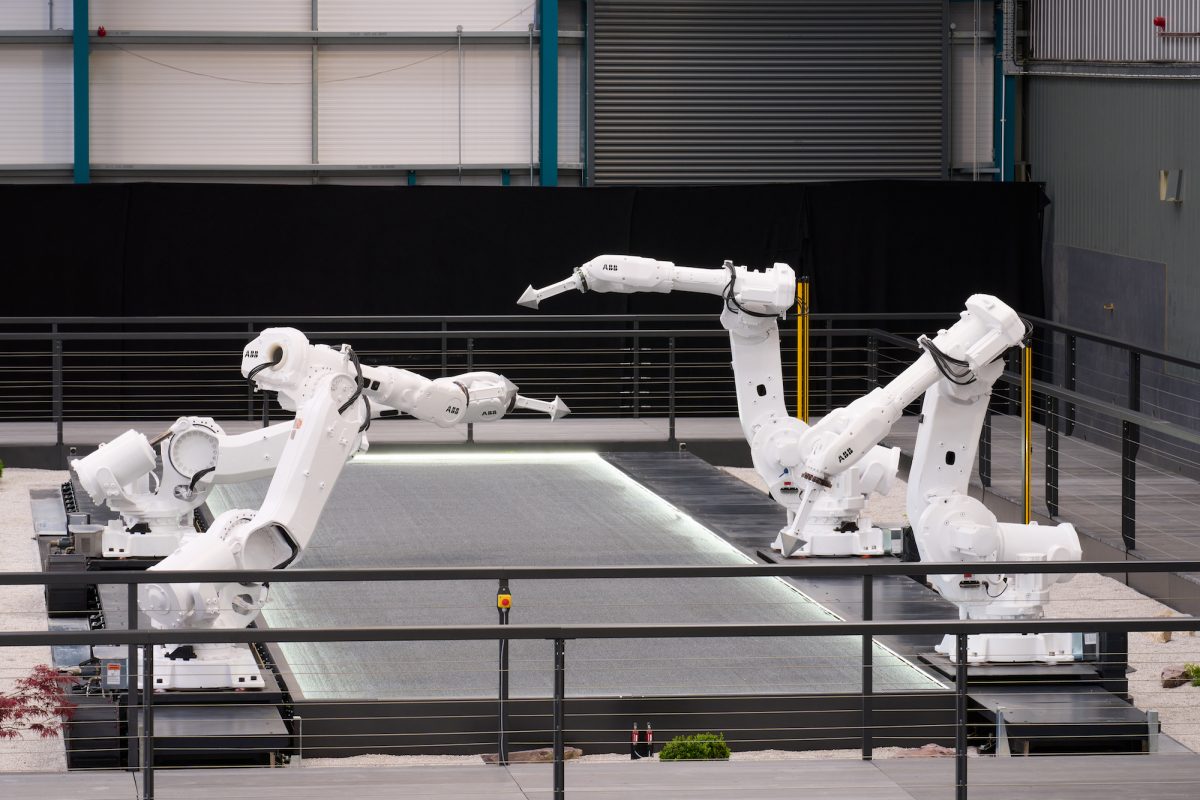

The Constant Gardeners combines specially designed operating systems, robotics and artistic automation. Video from Olympic and Paralympic games is analysed by the software, which removes background information before isolating the motion of the athletes’ bodies. The system then generates a unique, illustration-like design from these movements, which varies according to data type and what the technicians wish to highlight from each clip. Quantitative data (such as medal tables, the distance of a winning shot put, or one country’s involvement across different disciplines) is also converted into intricate patterns. Four robotic arms then inscribe the shapes into a bed of fine gravel, a sketchpad inspired by Japanese Zen gardens.

After pandemic restrictions ruled out plans to produce the work in Japan, a team from the East London studio have spent two and a half weeks at the Yorkshire plant troubleshooting the project. Once completed, the installation will be sent to Tokyo by boat and rebuilt in the central Ueno Park ahead of the games, which the International Olympic Committee insists will go ahead despite the state of emergency in the Japanese capital.

“Four robotic arms inscribe the shapes into a bed of fine gravel, a sketchpad inspired by Japanese Zen gardens”

“My interests and the studio’s research are a lot to do with movement; a lot to do with space syntax and how people occupy space,” Bruges explains as we stand on The Constant Gardeners’ viewing platform, a rectangular perimeter around the installation. A drone buzzes overhead, taking photos of the gravel. “It started with thinking about how people occupy buildings, and then that translated into sports and environmental systems.”

This project is a clear successor to Bruges’ work with both sports analytics and manufacturing robots: in 2011 the studio created Game Show, an interactive LCD artwork tracking the in-play movements on basketball courts at the University of Oregon, using an overhead camera and optical flow technology to create heat maps. In 2017 Bruges’ team re-engineered robots from a Land Rover production line in Where Do We Go From Here?, a kinetic artwork using light and sound direction to transform Hull’s architecture into an immersive cityscape.

The Constant Gardeners represents a fusion of the studio’s interests. It uses mapping and image capture to create a new visual language from traditional human movements, while also drawing attention to the precision, dexterity and artistic capabilities of advanced robotics. “It’s like choreographing a dancer,” Bruges says. “Some movements are quite volumetric, some are planometric, some are axonometric, some take slices through space.”

By demonstrating technology’s versatility and responsiveness, the studio challenges perceptions around artificial intelligence and the automation of characteristically human processes: in this case, the creation of art.

“The studio challenges perceptions around artificial intelligence and the automation of the creation of art”

The hangar’s yellow safety doors match the upright sensor posts surrounding the gravel rectangle, which act as a trip mechanism stopping the robots when technicians traverse the bed. Slanted blue beams and olive-grey walls warm the project’s cool, almost surgical aesthetic, while the design feels more uniform than a typical Zen Garden, crevices and meandering paths replaced by geometric order. The robots’ movements seem at once inquisitive and autonomous, but also rigidly controlled.

The four arms are attached to rails which run along the gravel bed’s long edges, one of seven individual axes of movement which allows them to cover the whole surface area. To orient themselves in space and avoid collisions, each arm must push a small silver lever located on the bed’s outer border before moving, after which it can draw to an accuracy of half a millimetre. The four aluminium teeth (modelled on the individual spikes of zen garden rakes) are designed to create a specific angle of repose as they cut through the gravel, stopping excess material piling up on the trough banks or sliding into the cavity.

The team tested hundreds of different types of gravel before settling on a final material, and used 18 tonnes in total. The gravel presented its own set of aesthetic considerations, which included managing colouration when the stones are moved or wet. The studio is also currently running tests so that the arms can wipe clean their creations upon completion. “The whole idea is that the artwork creates its own artwork: it’s a self-contained process,” Wadey says. “It generates the illustrations, it wipes them out, it goes again, which gives an ephemerality to each. You’ll only ever see it once and then it will be gone.”

Bruges returns to the idea of a palimpsest, where an initial inscription is overwritten with the original still visible, an act of accumulation and constant revision. The team uses the term ‘illustration’ somewhat reluctantly, as it fails to capture what Bruges calls the “more performative and durational” aspects of the process. “We’re thinking about them as keyframes in an animation,” he says. “So there are moments in time where you’ll see a freeze frame of something in the gravel. You’ll be able to see little nuances or moments from that activity or discipline, but what we’re ending up with is a product of all those things layered”.

Jason Bruges

“The artwork creates its own artwork: it’s a self-contained process. It generates the illustrations, it wipes them out, it goes again…”

One of the most difficult aspects of the project, Wadey says, has been “finding a way to harness this industrial technology so that we can work creatively,” or “hacking” the robots. The studio’s 27 full-time staff boast expertise across the art-technology spectrum, with designers from 3-D, product, industrial, interaction, computational and graphics backgrounds sitting alongside artists, architects, logistics and marketing staff, video analysts and installation technicians. “It’s almost like an orchestra, or creating a film,” Bruges says. “Everyone’s got a role, and some have leading roles. I’m sort of a conductor in this artistic process.”

But whereas orchestras coordinate to bring to life classical symphonies or age-old compositions, Bruges’ studio welcomes the subversion, and perhaps even the mixed reception, associated with repurposed robotics. The team is accustomed to viewers expressing discomfort or fear around their creations, fuelled by ascendant concerns around the perils of automation and artificial intelligence.

“We’re trying to create a different energy around them,” Bruges says in response. “It does feel meditative and it is quite mesmerising: it’s a whole new narrative around this type of technology.” He notes the anthropomorphised language used to describe the robots: arms, teeth, joints, shoulders, which retains a welcome link with the human and, crucially, elite sport. “We’re creating this synergy between the idea of the athletes honing their skills and the way the monks would’ve created waves and straight lines and zigzags in their meditations,” Bruges explains. “It’s the pursuit of perfection and this infinite cycle.”

All photographs by Emile Holba for Elephant