“The State Academy of Plastic Arts in Amsterdam, where young persons with wagging beards or horse-tail hair styles painfully try to have their impetuous artistry channeled into a bed of technical possibilities in the field of the Fine Arts.”

These words, in the April 1958 edition of electronics company Philips’ in-house magazine Announcer, introduced a report on Portrait of Present-Day Man, a performance involving a trio of experimental poets, electronic music and a robot named CYSP 1.

The language may be painfully dated, but the concept of a space where young experimental artists (complete with elaborate facial hair and ponytails) can explore the creative potential of new technologies would be just as familiar in present-day Berlin, Boston or Beijing.

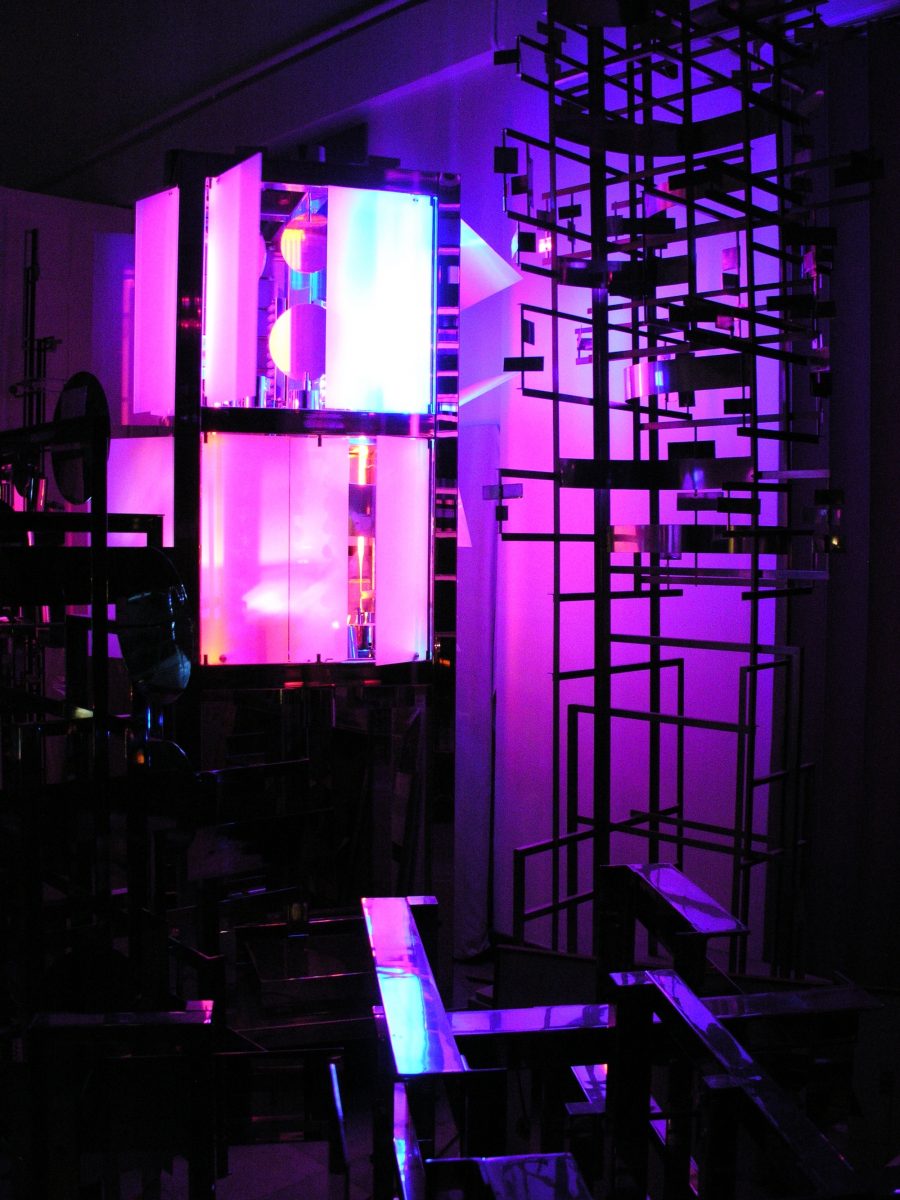

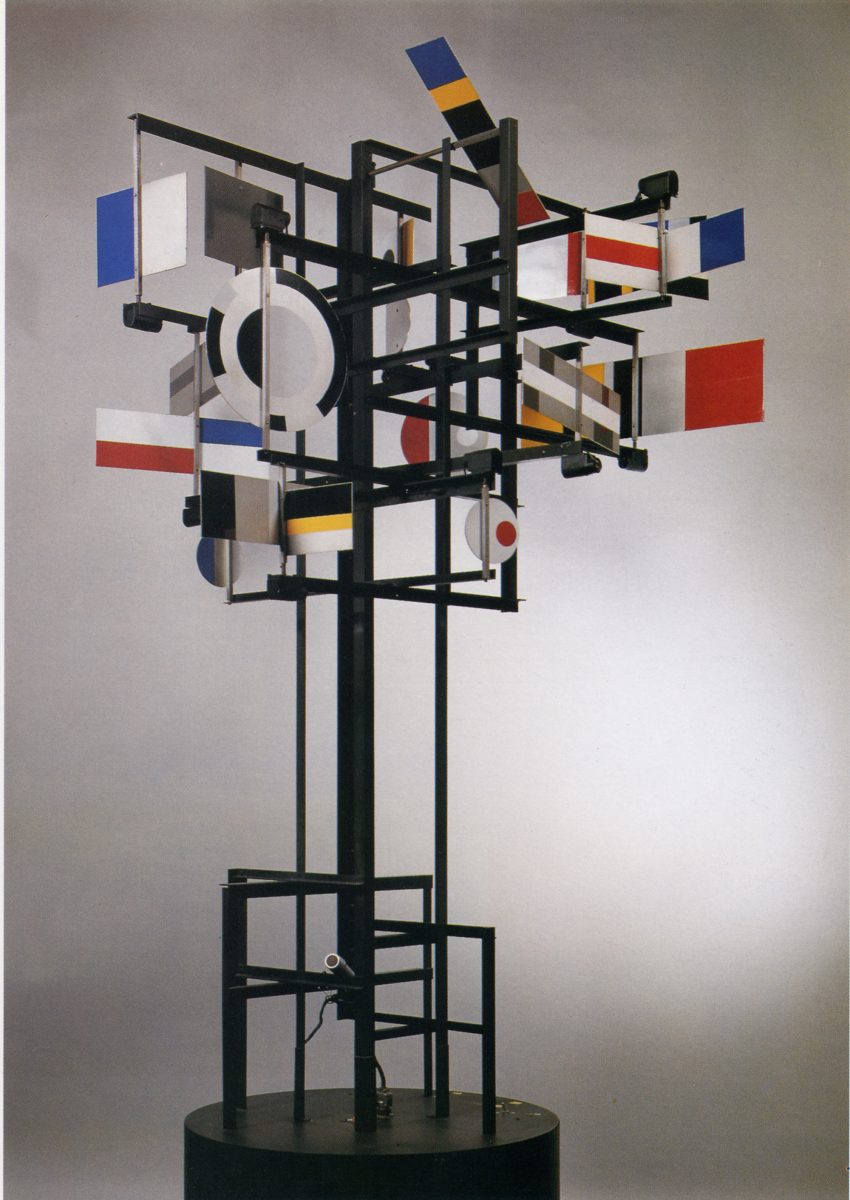

Portrait of Present-Day Man featured an assemblage of 16 multicoloured moveable duralumin plates on a motorised base with concealed wheels. It used a microphone and photoelectric cells to detect variations in its immediate surroundings, to which it responded autonomously thanks to an ‘electronic brain’ built by Philips’ engineers.

One of several collaborations between Philips and experimental artists during the 1950s and 1960s, CYSP 1 was the joint creation of the company’s French laboratories and self-proclaimed ‘futuristic sculptor’ Nicolas Schöffer.

Its name was a contraction of two terms; cybernetic and spatiodynamic. The latter term was Schöffer’s invention; the former had been popularised by American mathematician, philosopher and engineer Norbert Wiener in his 1948 book Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. Derived from the Greek word for steering, cybernetics revolved around the principle of feedback, where external inputs or stimuli are processed automatically to alter the way something, or someone, acts.

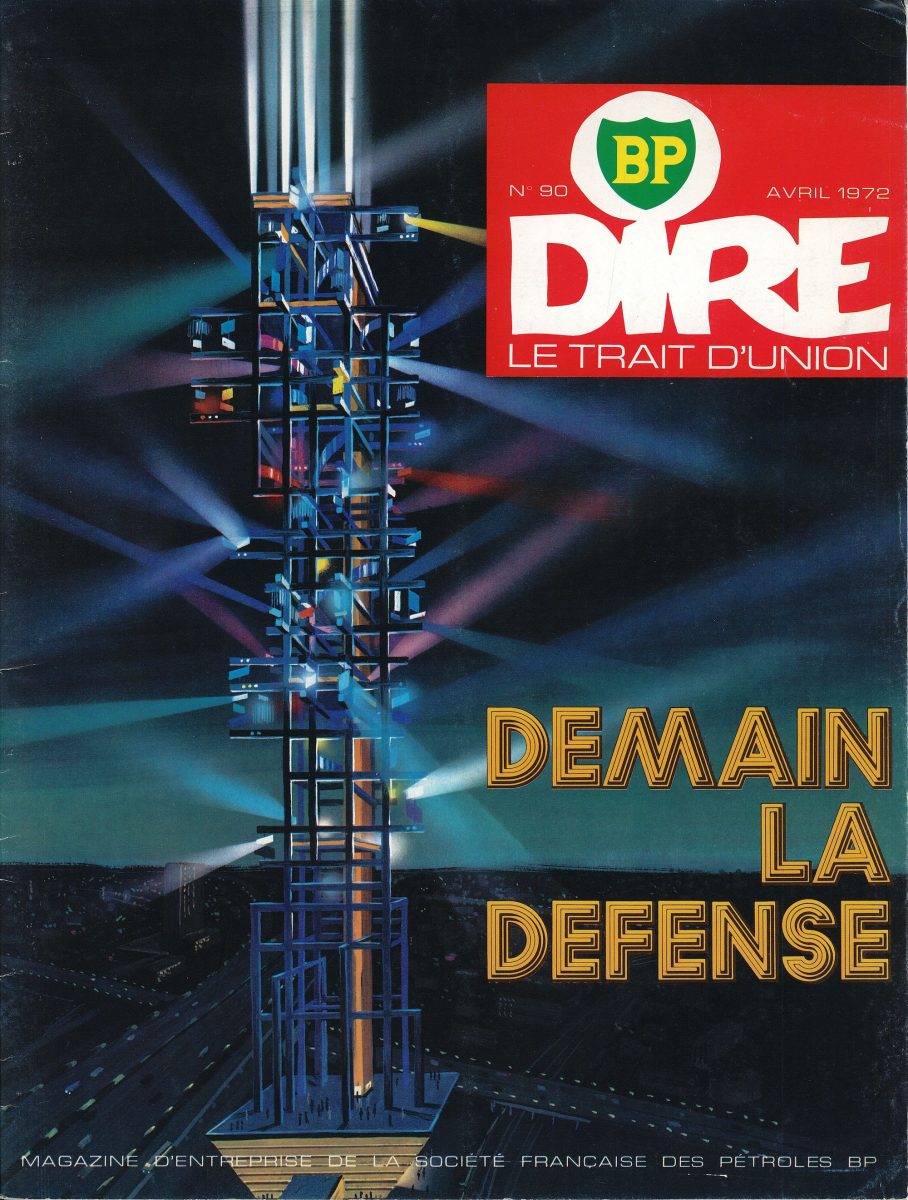

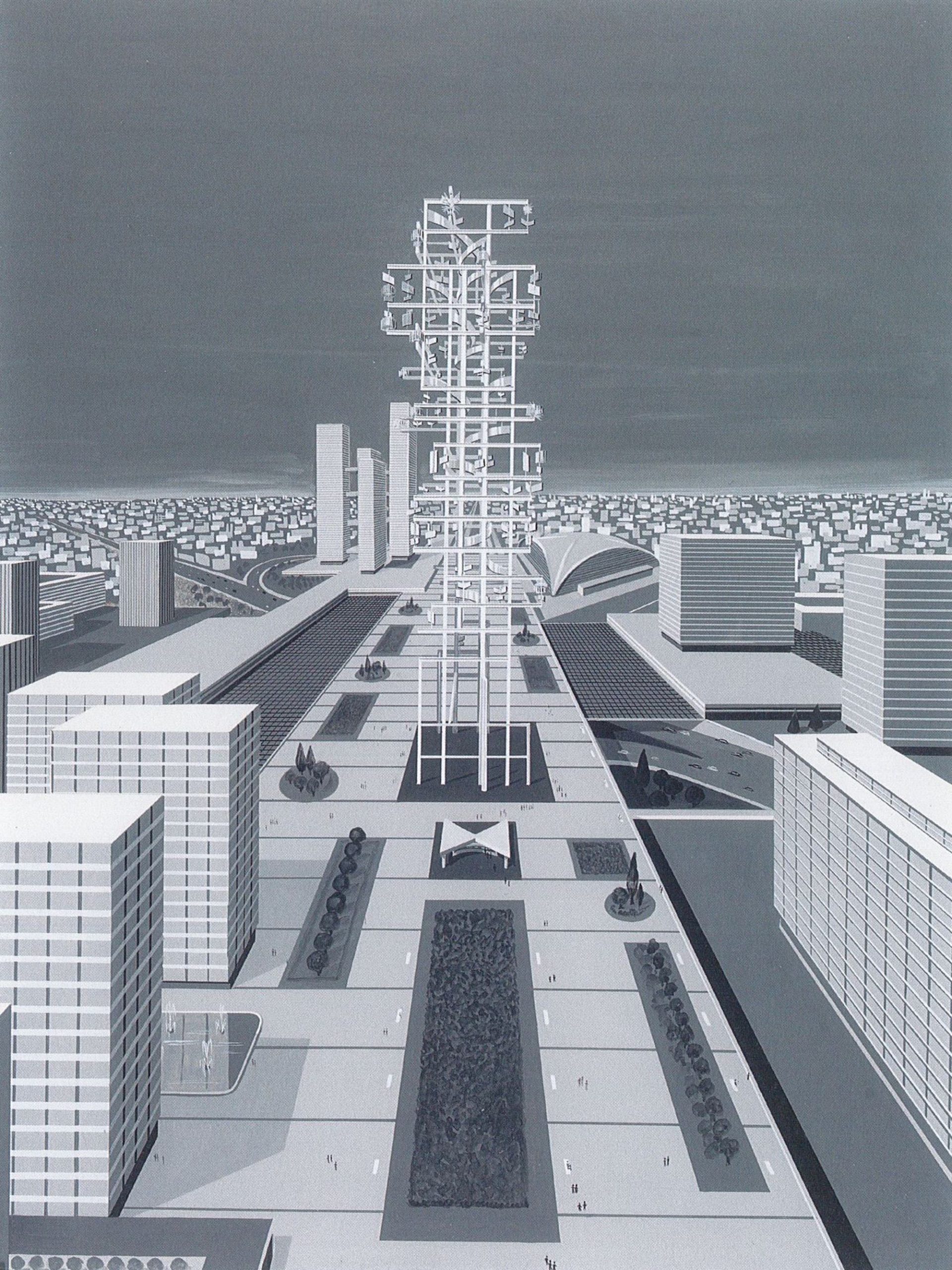

“His most ambitious scheme was for a 1,000-ft cybernetic tower at Paris-La Défense, a ‘massive computer/data-processing machine’”

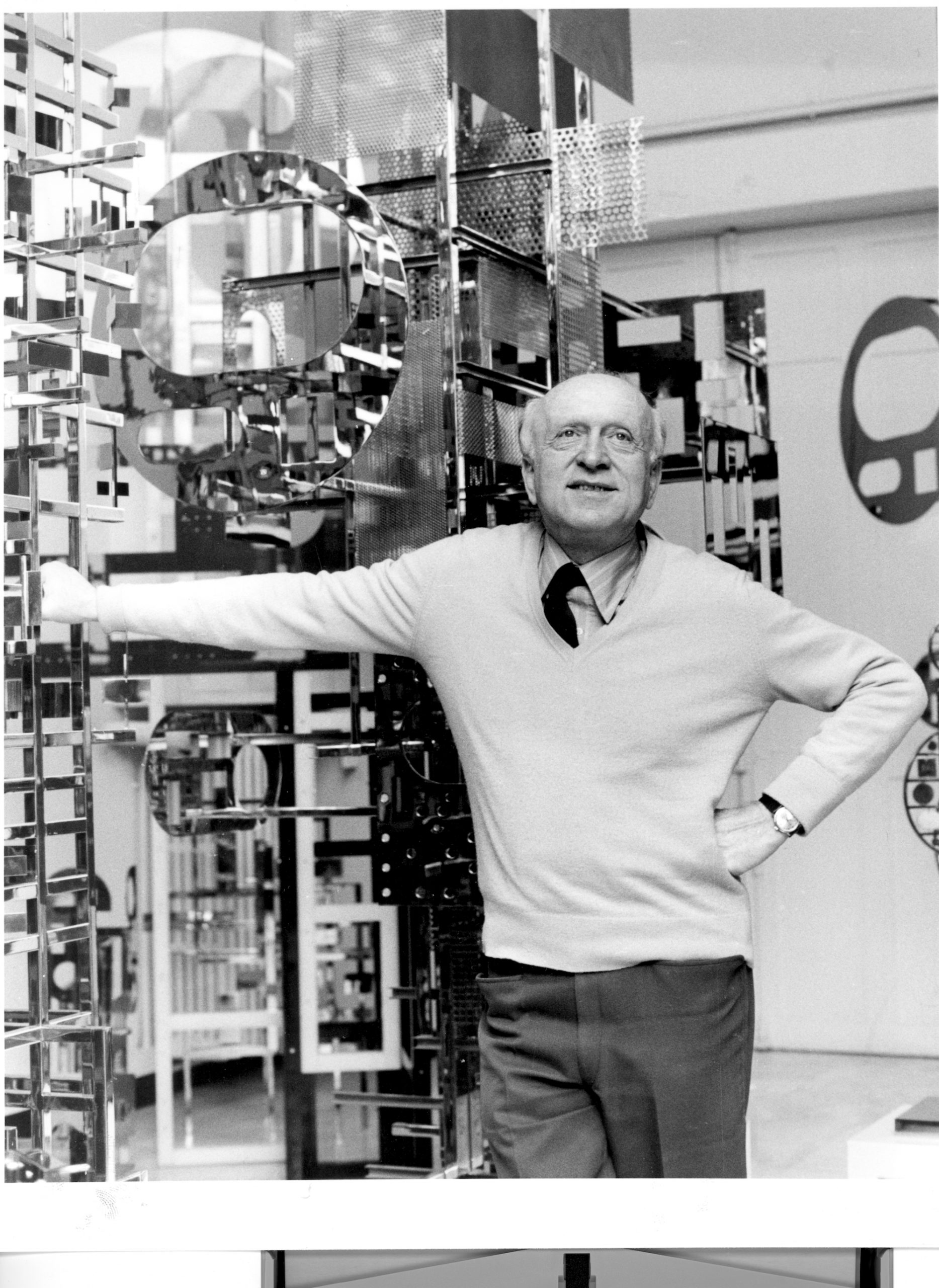

Schöffer was born in Hungary in 1912 and studied law and art in Budapest before moving to Paris in 1936 to study at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. He painted, exhibited and networked the Parisian art scene (one collector gave him a box of Cézanne’s crayons) until the German occupation of 1940 when he left for the Auvergne, where he fought for the Maquis resistance fighters.

He told Time magazine in 1955 that “under the shock of war I evolved into a different person. I began meeting intellectuals, I began sculpting new ideas”. Returning to Paris after the war, he experienced a rush of creative and intellectual energy, his fascination with Wiener’s Cybernetics coinciding with a shift from painting to sculpture.

CYSP 1 was not the first kinetic sculpture of the modern era, nor even the first to be moved by external forces (Alexander Calder had been making pieces moved by the wind since the early 1930s), but it is is considered to be the first cybernetic sculpture in art history. Schöffer’s innovation was to tap into the emergence of what we would now call artificial intelligence.

At the same time as he was integrating cybernetic principles into his art, they were also being adopted by disciplines that included economics, anthropology, computing, and organisation. Perhaps appropriately, recent renewed interest in Schöffer’s work has coincided with a cybernetics revival. One year after 2018’s Schöffer retrospective at the Lille Métropole musée d’art moderne (LAM) (the first since 1974) came the publication of Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski’s The People’s Republic of Walmart, a key text in the reappraisal of cybernetics as an economic and political toolkit.

Schöffer’s subsequent post-war career as an artist was all about “sculpting new ideas”, as he told Time magazine. He rode the surge in postwar innovation, assimilating new developments in science, technology and electronics, adding terms such as ‘chronodynamism’ and ‘luminodynamism’ to his self-generated theoretical taxonomy.

His output straddled sculpture, urban planning, architecture, consumer products, mood-enhancing machines, and even entertainment venues. It’s a model for the artist’s role in late capitalism that is commonplace today, but was only just emerging at the time.

Schöffer claimed adherence to artistic purity but was happy to design products for Philips and Clairol, contribute to several film productions at Cinecittà studios, collaborate on the interior of an iconic jet-set nightclub in St Tropez named the Voom Voom, and even provide the kinetic sculptural backdrop for a film of Brigitte Bardot performing Serge Gainsbourg’s erotic sci-fi song Contact!

- Both: © Paris, Archives Nicolas Schöffer. Courtesy Fonds de dotation Nicolas Schöffer, © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

“CYSP 1 was not the first kinetic sculpture of the modern era, but it is is considered to be the first cybernetic sculpture in art history”

Nevertheless, his avant-garde credentials remain intact. Over the course of four decades, he worked with experimental composers such as Pierre Henry and Iannis Xenakis before producing his own electronic compositions. He presented a prototype experimental house in Paris, co-founded the future-focussed Group International d’Architecture Prospective (GIAP), published La ville cybernétique (The Cybernetic City) and submitted, unsuccessfully, designs for the reconstruction of Les Halles in Paris.

Schöffer created performances, ballets, recordings, lightshows, theatrical pieces and a succession of his own films and specials on French TV. Numerous solo and group exhibitions of his sculptures were staged all over the globe. He was showered with prestigious awards.

In the later decades of his career, Schöffer concentrated his cybernetic efforts on a series of public sculptures and towers. These were erected far-flung spots around the world, including Saint-Cloud park in Paris, as well as Liège, Washington, Lyon, San Francisco, Bonn, Munich, New Orleans and his Hungarian birthplace, Kalocsa.

“Schöffer’s art itself was also uncannily prescient of our own computationally-controlled society”

His most ambitious scheme, for a 1,000 foot cybernetic light tower at Paris-La Défense, a “massive computer/data-processing and distributing machine”, started promisingly in the early 1960s with backing from the Minister of Culture. However, the project dragged on until 1978, when the French government decided that its ‘elitist informatics’ were no longer du jour. It was never built. The tower in Liège fared better, and was restored in 2015/16 with its electronics updated to include an integrated Twitter account.

Cybernetics went on to exert a significant influence on British art. Artists, critics and educators inspired by Wiener’s writings include Richard Hamilton, Reyner Banham, Eduardo Paolozzi and crucially Roy Ascott. The latter implemented his startlingly radical vision of art education in Ealing and Ipswich (where he taught musician Brian Eno) and pioneered the use of computers in art schools.

“Under the shock of war I evolved into a different person. I began meeting intellectuals, I began sculpting new ideas”

Cybernetic art may have peaked with the ICA’s 1968 Cybernetic Serendipity show, which featured Schöffer’s CYSP 1. But, according to art and computing historian Catherine Mason, “the historical relevance of this ground-breaking show continues… in almost everything we visually (and even aurally) consume.”

Something similar could be said of Schöffer’s art itself which, while rooted in the aesthetics, social preoccupations and technological optimism of its time, was also uncannily prescient of our own computationally-controlled ‘society of the spectacle’ (as philosopher Guy Debord described it in 1967).

Today millions of us voluntarily mediate our lives via social media, and feel lost in the city without the aid of a digital map to guide us. As omnipresent algorithms shape our online and offline experiences, it’s hardly surprising that Schöffer’s original belief in the programming of external technological forces continue to resonate.

Steve Taylor writes about cities, music and urban culture. He recently started a PhD on underground music scenes and the future city