There is a gay bar in my hometown of Weymouth, on England’s southern coast, called The Closet. It opened after I had left to study in London where I was, in fact, spending time in proper gay bars—The Joiners, The Vauxhall Tavern, G-A-Y, Heaven, Dalston Superstore—many of which are explored in Jeremy Atherton Lin’s Gay Bar: Why We Went Out. The Closet, despite its ironic namesake and the proud totemic rainbows draped everywhere, was, according to my gay friend, the straightest club she had ever been to. We joked that people didn’t seem to be aware of the fact that The Rumshack, Weymouth’s gayest, queerest, club, was located just around the corner and had been in existence years before the Closet opened, welcoming its regular cast of gender-bending clientele, white male metalheads with dreads and weekend crooners looking for karaoke spots to sing Sinatra.

The Rumshack is not a gay bar, but it certainly housed my small town’s misfits and exuded an aggressively exuberant, undecipherably queer atmosphere. Before I left Weymouth, I spent most weekend evenings there from the age of around 16. Saturdays became routine: willing the hours away in my shoe shop job where I stood hour upon hour like a statue; and then stealing away over lunch to buy patent platformed heels from New Look and cheap white wine so we could drink as we applied thick black eyeliner as the night started. The Rumshack was a strange sanctuary, a liminal place where we drank vodka and cranberry juice, where the DJ played anthemic 70s disco until five in the morning: a place where the world softened.

“Atherton Lin practices the historiography of gay bars, assembling a taxonomy of these spaces”

The bar area was a bejewelled grotto with pink plastic flamingos hung from the walls, sombreros adorning the ceiling, and stock pictures of 50s rockabillies. It was exaggerated, theatrical, sexy, grimy and sweaty. We didn’t know it at the time, but The Rumshack was pure camp: a melting pot of, in the words of Susan Sontag, the “exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naïve.” The Rumshack allowed us to attempt the extraordinary and the silly. It offered us pretend, transformational glamour, where we could escape the mundanity of school, days jobs, and the town that felt like it was too small to contain us. It also had its own indexical landscape: glittering British flags in black lame frames, tiki torches, pamphlets about local sexual health services, tampon machines scrawled with graffiti. It was a place where we were learning to cruise, to desire and to dance.

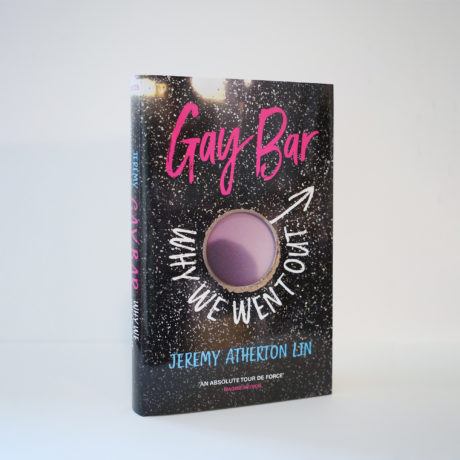

In Atherton Lin’s cultural history Gay Bar, he creates a palimpsest of queer ephemera and artefacts across gay bars in London, Los Angeles and San Francisco, describing how “a gay bar can be a repository for all the extra that doesn’t fit into other spaces.” As I read Gay Bar, I could feel the sticky, saccharine mixtures of cheap £1 drinks underfoot, and the wodges of wet paper made from old tourist maps or STI leaflets dropped to the floor as everyone around dances to Go West. As Atherton Lin begins his foray into LA clubs like Probe and Studio One, and club nights like Popstarz in London, he begins to trace an intricate topography: an index of gay bars and their mirrors, bathrooms, décor, DJs and regular patrons. Atherton Lin practices the historiography of gay bars, assembling a taxonomy of these spaces. Even the music seems to echo across these different spaces: Mary J Blige’s Family Affair radiates from a jukebox in a bar called the Phone Booth in San Francisco and then many years later, we hear the same song in the Royal Vauxhall Tavern in London.

Gay Bar is as much a love story across continents as it is a work of cultural historicism. After tracking his time from Los Angeles to a long stint in San Francisco, Atherton Lin and his partner—who adopts the moniker Famous Blue Raincoat—settle down in London. Their neighbours, Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings, are the artists responsible for creating the UK Gay Bar Directory (2020). They visited and filmed over a hundred (empty) venues as a way to explore how identity is “not just inscribed on our bodies but articulated in the places we inhabit.” Hastings and Quinlan’s film is a different type of archive to the one that Atherton Lin sketches in Gay Bar, but both luxuriate in the auratic fantasy that gay bars offer in the construction of our identities.

“Atherton Lin is aware of the intensive, deeply personal labour behind the fashioning and production of gayness”

UK Gay Bar Directory is prophetic, and the bars and clubs it documents, as Atherton Lin suggests, seem “at once spectral and pathetic”. Gay Bar Directory pans across deserted bars and pubs, responding to the overwhelming decline in gay and queer social spaces as they are eaten up by austerity, real estate development and gentrification. Relics abound: faded, sun-bleached rainbow flags; disco balls; strings of fairy lights suspended over DJ booths like chicken wire, both inviting and prohibitive. Such objects, in their desolate, unpopulated environments, are left open-ended: music plays, lights still pulse, but the rooms are abandoned and any human presence is eradicated. Can these places continue to signify as gay without those that occupy them?

Through the accumulation of these spaces on screen, each bar, with its velvet and satin cushions or jukebox, offers a different persona. Like UK Gay Bar Directory, Gay Bar too seems to suggest that gay pubs or queer nights often belie a unified gay identity that easily maps onto one’s own. This is perhaps the catch-22 of the gay bar: as Atherton Lin articulates, we go there to feel part of something—to feel gay. However, in doing so, he also reminds us of the aspirational and inherently othering work of gay identity: that in its freedom, the capacious possibilities of such self-fashioning also present their own limitations. Like the dance floor of The Joiners—where someone might hastily slam their shoe on your toe, or where you might run your hand up the sweat of someone’s back—the animating force behind Gay Bar is Atherton Lin’s canny ability to detail how identity is shaped by those spaces and people you might bump up against, happily or not.

“Strings of fairy lights hang suspended over DJ booths like chicken wire, both inviting and prohibitive”

As we move from one bar to another, Atherton Lin is aware of the intensive, deeply personal labour behind the fashioning and production of gayness.

When he first moves to LA, he is “unsure about what kind of gay” he wants to be, especially in 1992 when, he says only half-jokingly, he was “against gay visibility”: “The visible gays did not make life any easier for me.” He carefully formulates how gay bars can foster segregation or exclusion along gendered, racial and class lines, as well as how spaces of self-definition are often unwittingly metered by the perceptions of others. During his time in LA, Atherton Lin visits Gold Coast Bar in West Hollywood, a place that has sparked his interest. Inside, he meets another man, who pats his thigh paternally and “told me I was too good for the place.” “I couldn’t see how that was possible,” he recounts, “I’d made the choice to go in.”

Such a moment encapsulates what is so refreshing about Atherton Lin’s intervention in Gay Bar. He not only paints the jouissance of the gay bar, but asserts that our forays into them are always a process of appellation and individuation, that so often self-understanding is defined by our complex entanglements with others. The surprise that this avuncular figure might somehow perceive something intangible beyond Atherton Lin’s own preference for how to spend his evening—or what he might be looking for in terms of fun or pleasure—is what can be surprising, confusing, frustrating and alienating in the game of identity.

This isn’t necessarily to the gay bar’s detriment, but Atherton Lin is all too aware of how policing the door is part of the gay bar’s conditions of possibility. As liberatory as gay bars can be, he tacitly locates how queerness often tails back on itself, ouroboros, becoming as regulatory as it is freeing. “It was becoming apparent that being homo did not amount to being the same,” he writes. At one point, Atherton Lin’s sister comes to visit him and Famous Blue Raincoat in San Francisco, and she comments on the trios of men passing them by on the streets of the Castro. Atherton Lin reflects that “some of us were allergic to ourselves—or had an intolerance to the construction of gay, to its trappings”. In moments like these, Gay Bar finesses the memoir genre, exposing the tectonic texture of carefully, painstakingly defining the self.

“In its freedom, the capacious possibilities of self-fashioning also present their own limitations”

In San Francisco, Atherton Lin articulates his affection for the term fag. “Fag was a firecracker, not a disorder; neither was it cringeworthy or falsely optimistic…In other words: not gay.” Fag is something explosive and authentic whereas words like ‘queer’ for Atherton Lin are too academic, too “sexless”. Instead, he wants to use words that were “about libido, leaked precum, were a bit handsy. Queer was about slipping through categories, whereas I preferred words to firm categories up—otter, pig, cub, kitchen, top, bossy bottom, slut—denoting the types I wanted to fuck, then write about later using the slang.” Both Famous Blue Raincoat and Atherton Lin want to be better students of gay history. Being gay isn’t only a lifestyle, but Gay Bar tacitly suggests that can also be a part of it. As Atherton Lin himself says, “I didn’t know how else to learn history but to try it on.”

Gay Bar tracks how queer communities come out with gay bars. As much as we make them—with our dancing, cruising, furtive glances, our sweat—these bars, in turn, make us. In Gay Bar, sexual identity is an ever-evolving threshold, its boundaries and limits constantly shifting, where queer identity might circle the dance floor, unsure or unabashed, turned on, or alert.

I’ve not read a book like Gay Bar before, and haven’t put it back on my bookshelf yet. Perhaps because I have been thinking a lot recently about what sort of gay I am, about how freeing it can be to luxuriate in the difficult self-fashioning territory of queerness—in the culture, the music, the books. Perhaps because it reminded me that as much as, for me, going out is about dancing or cruising or community, it is also a complex project in the desire of the self, about who we are and who we want to be. Perhaps because Atherton Lin offers an unprecedently honest and authentic portrayal of how uneven, aspirational, messy and sexy being gay—let’s also say becoming gay—actually is. Through the space of the gay bar, Atherton Lin reminds us that fashioning our identities can be painful, erotic and sexy.

Come As Softly is a book column by Bryony White on intimacy, desire and sex.