It is often surprising meeting people you are familiar with through images, both still and moving, as they never look quite as you imagine. When meeting someone as shape-shifting as Gillian Wearing, the possibility of their image aligning with the mental one you have of them is rare. When I met Wearing at the Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK) in Copenhagen, where she is currently showing Family Stories, I was curious to see how the “real” artist looked.

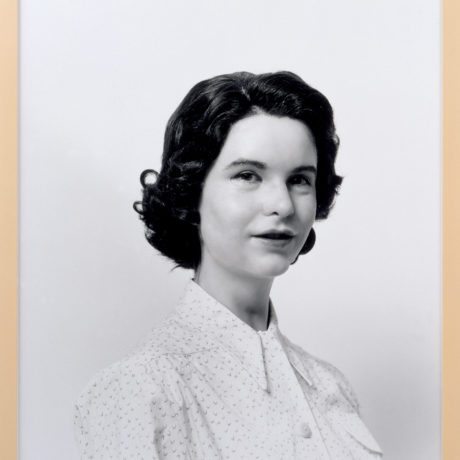

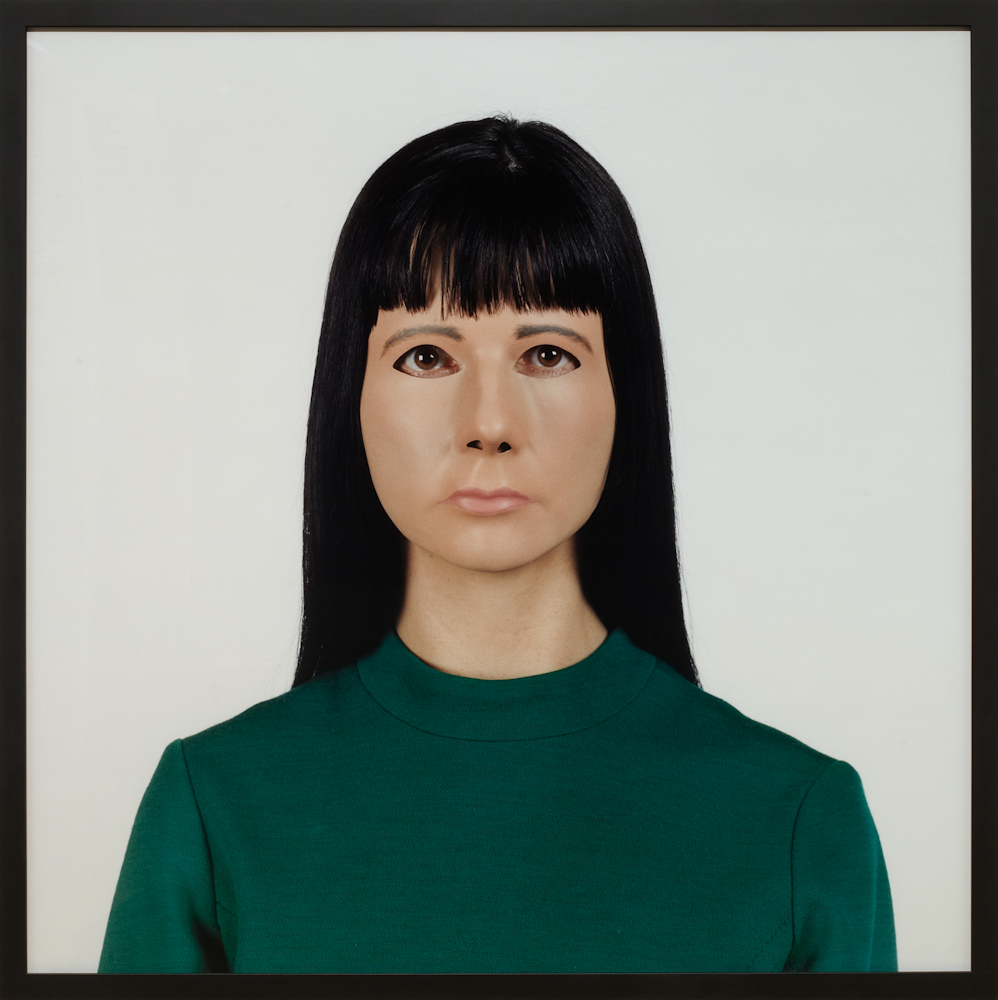

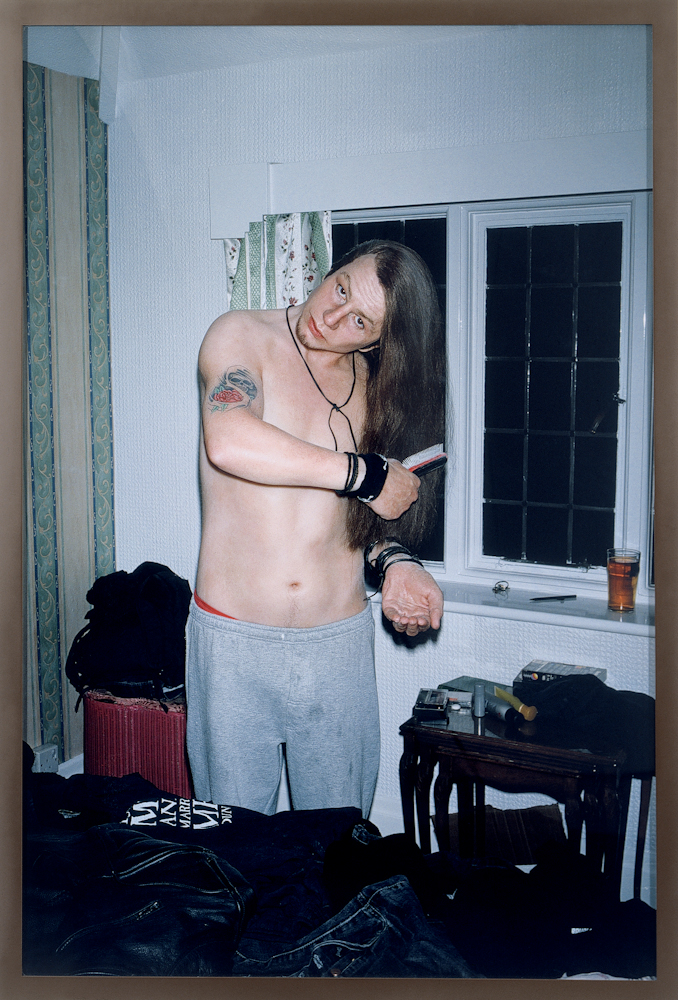

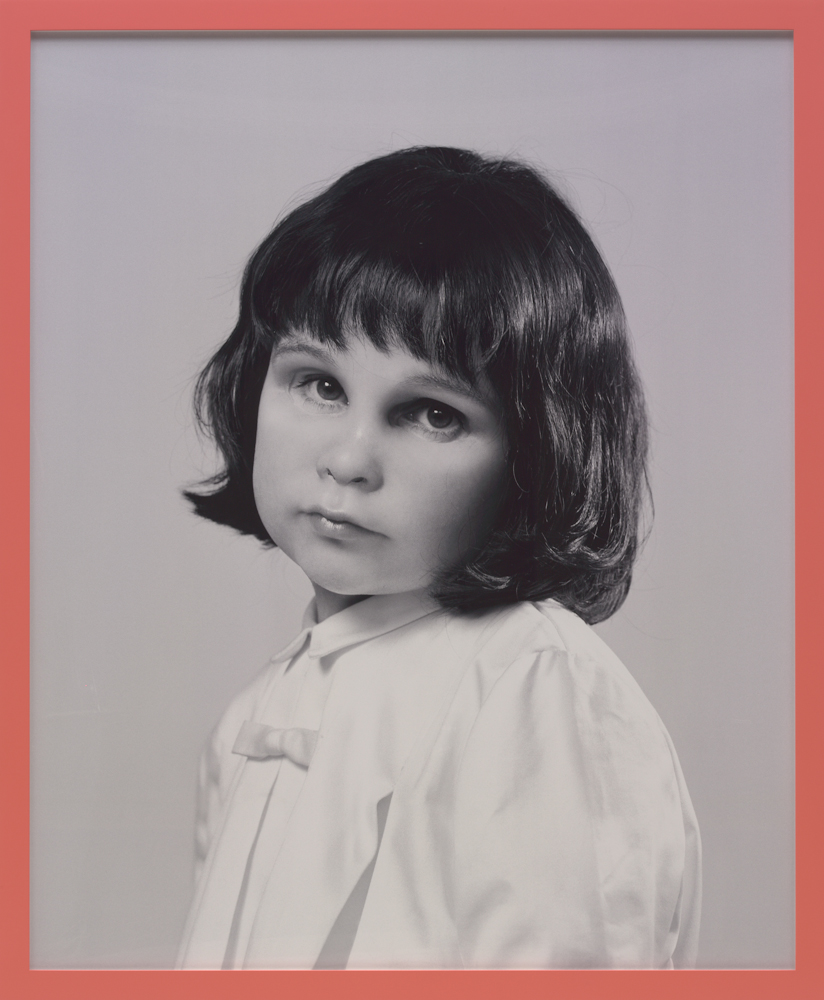

Over the years I have encountered many of her self-portraits—especially the ones from the series Album (2003), where she wears astonishingly true-to-life masks of her family members or herself at a younger age—and scanned every single detail in search for a glimpse of the reality behind the accurate fiction, the present moment behind the reconstructed past. Wearing’s work, in general, is something one doesn’t simply view, but rather examine: just as the subjects of her video pieces don’t merely talk, but carve themselves open, and we as the audience don’t simply listen to what they have to say, but hang on every single word.

The exhibition Family Stories at SMK is an exhaustive retrospective which gathers a wide range of works from the artist’s production, from the famous Signs That Say What You Want Them to Say and Not Signs That Say What Someone Else Wants You to Say (1992-93), where she stopped passers-by in a busy area of South London and asked them to write down what was on their mind, to the most recent project, a series of human-sized sculptures of family units where she investigates the notion of family as a setting for personal identity and for society. A Real Danish Family, the third and most recent sculpture of the series, was installed in the open space in front of SMK during the show’s vernissage. It was made in collaboration with the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DR), the City of Copenhagen, Kunsthal Aarhus and SMK, and saw the launch of a nationwide campaign and a TV programme to choose one family to be cast in bronze among a selection of 500.

It’s a real pleasure to meet you in person. During your career you’ve gone from a more direct approach and a bald use of media, such as street photography, to bronze sculpture and elaborated object-making. If this is a specific direction you’re taking, it seems quite natural to juxtapose it with the growing immateriality of our age. To me, it seems like you try to create something that is permanent, while all the rest is less and less stable. What are your thoughts on that?

I see this kind of evolution in my work, but I haven’t really thought about it in terms of materiality or immateriality. When I was at university, I made works in all different media as I knew I wanted to be flexible. I’ve always been curious about how I can mutate something sculptural into photography, and vice-versa. With the signs series from the nineties, you could see the physicality of the people but also their thoughts; then I moved into confession videos, where you hear people’s inner thoughts while they wear a mask, and this led to me having myself photographed, masked as members of my family. At that point I saw it as a two-dimensional sculpture. And after that I started creating three-dimensional pieces. While I’m working, I’m not consciously deciding that I need to move into a specific area. It’s what I’m doing that informs the next choice, in some way.

It sounds like a path where one step naturally follows another. The outputs might differ, but the inner drive seems to be the same: you represent people while giving the audience an extra layer of information about them.

Yes. When I start a new project I don’t pursue what makes more sense, I’m rather drawn into my own experience of my previous work. It’s a sort of instinct that feels right for me while I’m doing it. The family sculptures are a suitable example of what you say about the presence of a constant need in my practice: they comprise a documentary element in the same way my photographs do. I actually see them as documents in themselves, but they contain more than meets the eye.

Photo by Heine Pedersen

The family is currently undergoing an important reinterpretation, I’m fascinated by the act of casting families in bronze. Also, choosing one type of family instead of another has some implications, when it comes to creating a long-lasting object charged with symbolic meaning such as a statue. I am curious to know a bit more about the process behind it. Who selects the family to be cast? And how?

The project was started in 2007 in the city of Trento, Italy, on the occasion of an exhibition I had at Galleria Civica di Arte Contemporanea. My intention was to present a new body of work together with previous ones, so I asked Fabio Cavallucci e Cristina Natalicchio, the curators of the show, how the climate was in Italy at that time. They told me there was a lot of discussion about the very low birth rate, I think in those days it was the lowest in Europe. The nuclear family, the one with two parents and two children, was about to disappear, so my idea was to look for a typical nuclear Trentino family and make it eternal. Families came forward through newspaper adverts, but it wasn’t me deciding which family to pick: we created a panel comprising a priest, a sociologist, some educators and the curators. I don’t speak Italian and for me it was very important that the choice was taken by people local to the area.

The second family statue was made in Birmingham, England, where I was born. Working with statisticians, I discovered that one single person can officially constitute a family, and this includes widowed, divorced, single for choice, students and so on. So on that occasion I wanted to open up the parameters, the way a statistician would do: absolutely anyone could apply, any family model, a group of friends as well. This, of course, led to a very different result. I am glad of the project’s openness, because it makes it unique every time, and strongly related to the place where it happens. In this sense, an important part of the project is that it’s constantly subjected to a spectrum of nuances that are given by the context.

You’ve recently worked on the third family statue in Denmark, in collaboration with a number of important public institutions. The influence of the context that you mention is very evident: from my understanding, the process was about finding a common “Danishness” in a wide range of family constellations. In my opinion, the project ran on a double line: one was to question the notion of family, the other was to reinforce a certain sense of national belonging.

Your feedback is interesting to hear because it opens up the way of looking at the project for further dialogues. I suppose what differs here from the other two episodes is the scale: the first two were located in a city, while this one is representing a whole country. It was not my idea to operate on the national territory and to make a TV programme out of it, but I embraced it and it worked well. What’s interesting for me in this project is actually what people can discuss from it. It has a strong sense of community because it brings a lot of people together. It’s actually the most collaborative work I’ve done so far.

Your art has been called confessional, as it touches on people’s deeper secrets and troubles. In your work Trauma (2000), for example, you asked people to describe intensely personal childhood experiences while wearing a mask. Today social media has greatly influenced the meaning of privacy and how we manage what we have to tell: especially teenagers. Has this change affected your art, and if yes, how?

I’m very aware that people are now able to communicate through their own medium. What I found fascinating about working with confessions and inner thoughts, and the reason why I operated in that area for so long, was that back then people really needed to express themselves, but there weren’t many formats where they could do that. I particularly realized that the opportunity of being able to tell something important for them while remaining anonymous was kind of special for the people involved. Of course, the new scenario introduced by social media has made me think that I have to take my work in a new direction, where I can still operate the role I had then, but on different premises. There’s still so much to do and to say about people! As a staple, there is the idea of not adopting fixed parameters for looking for a particular subject.

Social media can undoubtedly be seen as a freeing and empowering tool, but it can also be highly critical and negative. Do you see this contrast as an interesting space to explore through art?

Any new medium has its pluses and minuses. What is more important today is to help people navigate themselves. I guess we should start educating children about it in school because it’s probably something that is best to learn when young. At the same time, technology is evolving at such a rate. Snapchat was born in a way that most messages sent over it are automatically deleted once they’ve been viewed or have expired, but then, of course, people found out some trick to record and share them. I’m so fascinated by our relationship with new technologies: how we adapt them to our need, and how they change us as human beings. Whatever you are engaged with, even if it is simply watching TV, it changes who you are and your perception of the world, so suddenly it becomes something very real and present. Some effects of this process are going to be good and some of them, we don’t totally know, I suppose. And when we get to understand it, something else will come along.

One last question: have you ever felt constrained by certain labels or definitions given to your work, or to you as an artist? I’m thinking in particular to the “female artist”: my impression is that people expect from a female artist that she deals with certain topics in a certain way, accordingly to her gender.

I don’t feel there is any one label that has been totally addressed to me. About being called a “female artist”, on one level it’s maybe an attempt to redress the balance after decades of women not having the access to art in terms of numbers in solo shows and all this, so there are good things about it. On the other hand, you certainly don’t want to fall into being labelled. Personally, I have never felt constrained or limited by a particular definition. When I made my first works, people often didn’t know who was behind them or what my gender was, maybe because of my name. Even if Gillian is quite a common name in some countries, in the past I have been written about as it being a man!

Images: © Gillian Wearing. Courtesy: Maureen Paley, London; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York