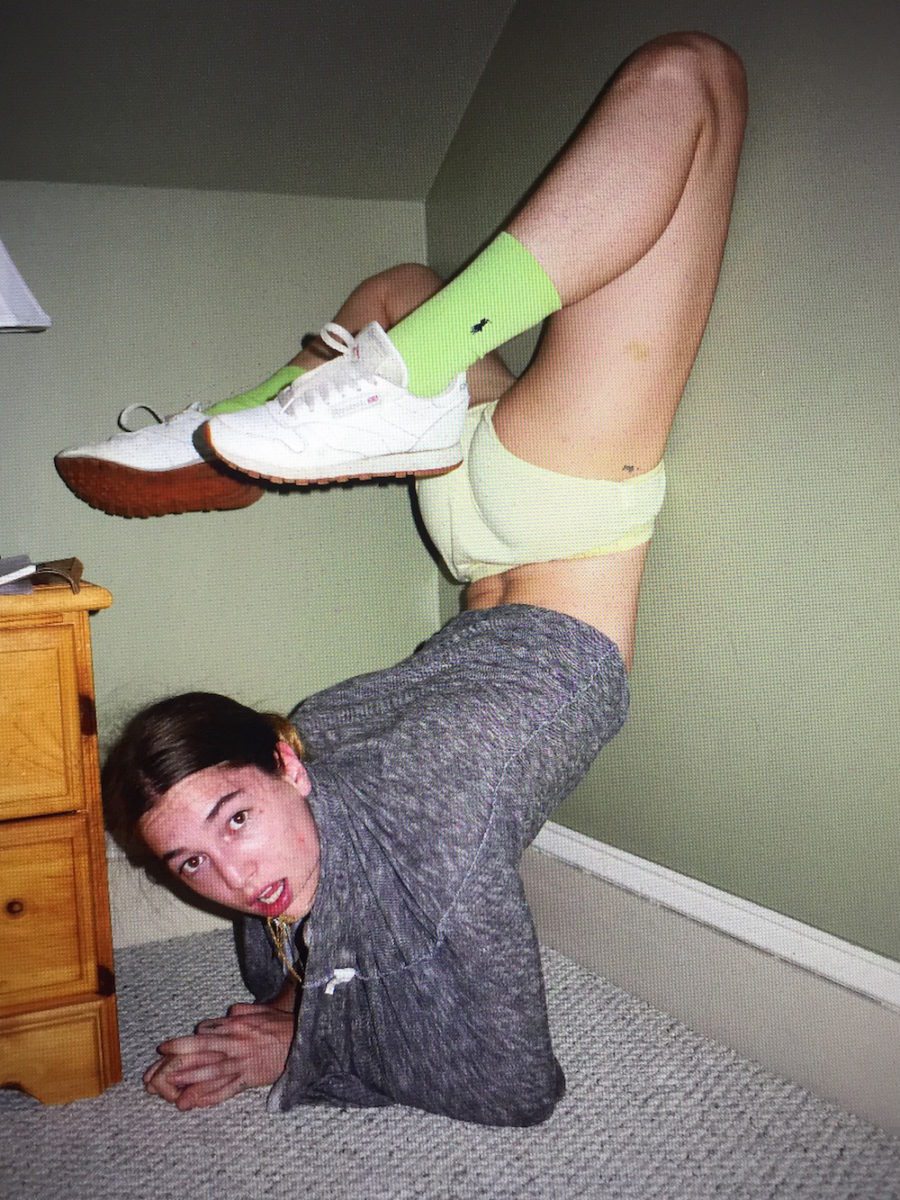

In the course of doing my research for Girl on Girl, Alexandra Marzella’s was among the work I came across that most confused and irritated me. Perhaps it was the fact I couldn’t relate to the many titillating stories about her personal life—a sugar daddy, model looks, spliffs, a fancy New York apartment, erotic dancing, posing for Richard Prince—that overwhelmed any reflection on her art. Then there’s the fact that her art in itself is so hard to pin down.

But the more I looked at her work—IRL and URL performances, self-critical and self-confident spotlights on personal and universal behaviour—the more I realized that work like this should be included in a deeper critical conversation. With her analysis of the misadventures and malfunctions of the self, and the unsettling sensation of seeing the self looking at the self, Marzella is one of the disembodied voices representing her generation’s experiences.

How do you articulate your relationship to sex in your work?

I’m not into compartmentalizing my life. Sex has been a part of my world since I can remember—I never understood why I should be ashamed of my innate tendency to explore my sexuality until my mom sat me down around age five and told me touching myself was like having sex with myself and I was to do it in private behind closed doors only. That was pretty heartbreaking for me at the time. I’ve masturbated since infancy. So I guess I’ve always been sexually liberated. I was taking nudes and sending them to boys I liked at age 12. My Barbies and sims were fucking on the regular. So it’s always informed and been an integral part of my artistic practice. It’s an integral part of all existence.

For the people who are lucky enough to be able to have sex…

There’s endless ways to have sex. Sometimes all you need is a thought.

In her scum Manifesto Valerie Solanas wrote: ‘man can not progress but merely swings back and forth from isolation to gang-banging.’ Why can’t we get beyond discussing sex (to get to ‘antisex’ as she calls it)?

Firstly this quote is referencing males, not all people. Why would anyone want to stop discussing sex? It’s the most natural thing in the world. If anything the 1900s did just that, criminalized everything that didn’t fit into a very specific, religious mould. What we need to stop doing is labelling and categorizing gender, race, age, sexual orientation and beliefs. Sex is something that is congruous amongst all beings. I don’t care if you shun anything sexual from your life completely, it’s still a part of our world no matter what.

What’s the problem with privacy?

Sex is a large umbrella, maybe more of a giant circus tent. Nudity is sex, or has been condemned to be. I’m all about alone time, one on one, small gatherings, etc. But privacy feels invasive and un-intimate to me at this point. I’m not referring to having sex behind closed doors, I’m talking about how communication, honesty and confrontation have proved to be, for me and many others, healthy ways of experiencing and navigating through life. Truth prevails. Privacy is the opposite of openness…which umbrellas these concepts. Shame is something I associate with being private. There are no thoughts, feelings, habits that are not shared between individuals. There is nothing to be ashamed of. Everything is relatable. The implementation of privacy on such a grand scale tends to make this a moot point.

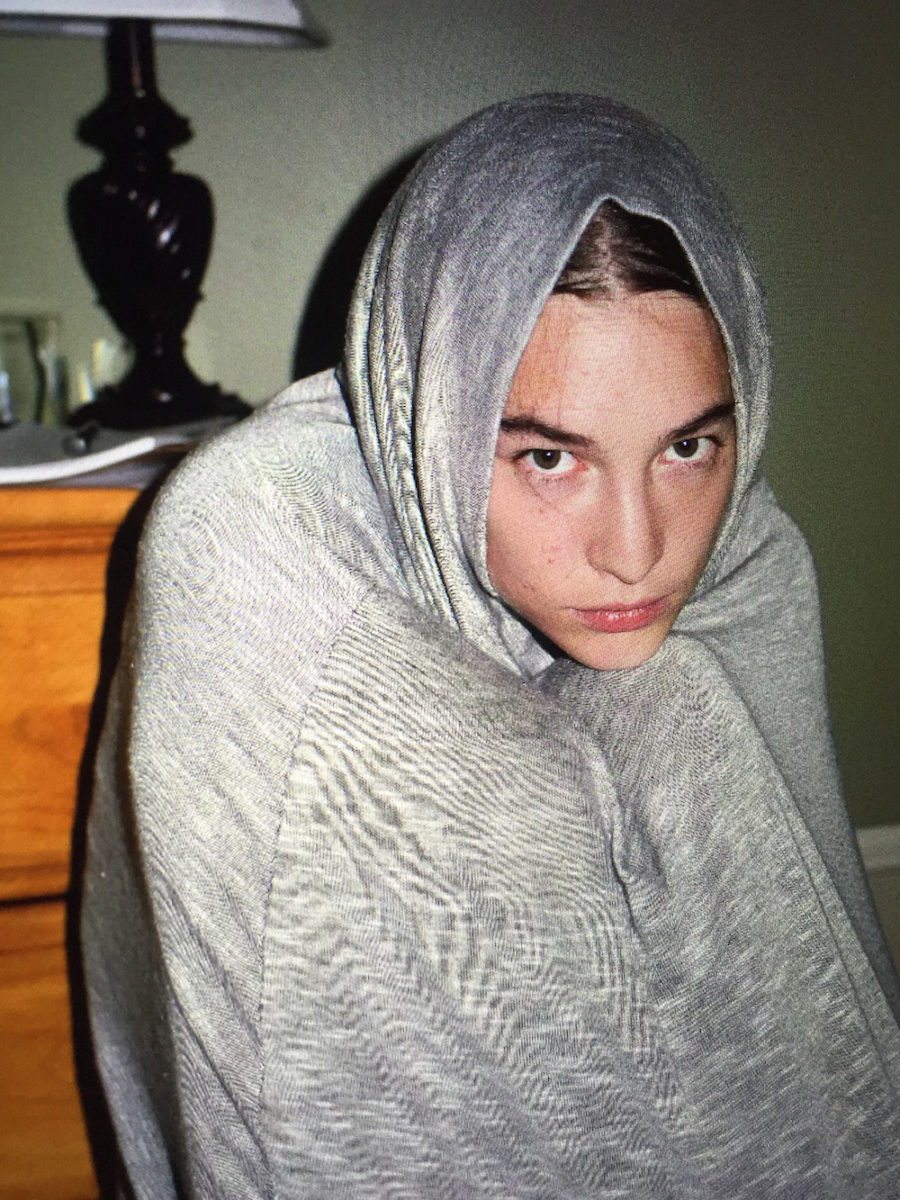

Which brings us nicely to your role as an artist. Instagram could be viewed as part of your practice. How much time do you spend on it?

Enough. There’s an app that I could download to figure it out but I’d rather not. Sometimes I’m on it all day. Other days I don’t look at it at all.

How do you view your Instagram?

Some people seem to think my Instagram is my entire art practice in itself. But I just think of it as a stream of consciousness in images. A diary of sorts. Something I can look back at some day and have myself a little chuckle over. At this point I can’t deny that it’s definitely a part of my practice. It informs career moves here and there. It links to all my other accounts and therefore lives beyond the app.

What do you yourself consider to be your art, then?

Everything is Art. I’m a multidisciplinary artist. I’m an actor, dancer, performance and fine artist, and I model. I want to do everything. Curate, make music and more.

The comments some of your works elicit are revealing: ‘Are you a stripper, and why does your panties look like diapers? Also this isn’t art, but totally fappable. Post some tits’ [on your YouTube video Ally x Anna x Artwerk6666]. How, as a feminist, do you deal with such misogynistic responses? How much of your audience do you think is following you because of your image?

It’s not so much about dealing with sexism and misogyny for me. But I’m a feminist, of course. I think it goes a lot deeper than men against women or unequal rights between sexes. Humans are obsessed with being evolved. I believe in both reality and fantasy. I believe we’re all perfect and always have been/will be. Sometimes I think about how a lot of my followers are probably men who think I’m attractive. It’s too bad but not surprising. It’s obvious that selfies can be a positive thing for the person who takes them, but it’s not a given that they have a positive effect on others.

- Alexandra Marzella

When I look at some of your work, I feel slightly depressed about my own appearance. It’s also, for me, depressing in a way to see the feedback that images get—more positive attention than other kinds of achievement. It’s a system that bothers me because it naturally leaves many people behind.

This is all true, yes. I’m sorry I make you feel that way. That depresses me too. I feel the same way a lot of times as well. But it’s a trap. We have been conditioned to feel bad about ourselves often. It’s hard but possible to reprogramme.

This feature was originally published in Issue 25