It is a truth universally acknowledged that a girl having too much of a good time must be punished. While male hedonism is traditionally lauded as evidence of virility, daring, and free-spirited adventurism, or accepted as an essential element of an ‘artistic temperament’ (hello Hunter S Thompson, Keith Richards, Jackson Pollock et al), in women it is more likely seen as a sign of trauma and impending tragedy.

In Western patriarchal culture, female pleasure has historically been regarded as threatening, and so, any woman who recklessly pursues it must also be a threat, something to be tamed, controlled and neutralised. Nice guys might finish last, but fun girls get finished off. From Eve in the Garden of Eden to Lindsay Lohan going out on the town, a girl doing as she pleases typically portends a fall from grace.

I have always found this cultural trope to be unbearably unfair. Why should men have all the fun, while girls are warned to watch their language, their behaviour, their drinks? In my postlapsarian state, trying to have as much fun as possible seems to be one of the only good uses of my time. To put it simply, life is short and parties are great.

Yet in a world that regularly chastises women for being ‘too much’ and for taking ‘excessive’ enjoyment in ‘frivolous’ things, insisting on the value of pleasure and parties is nothing short of subversive. This is why the Party Girl has long interested me.

Marlowe Granados’ recent book Happy Hour refuses to separate the frivolous and the adventurous. Following the escapades of bright young things Isa Epley and Gala Novak as they grift their way through a New York summer, Happy Hour revels in “nylons and lipstick and invitations”, revealing how they too can transport girls to fantastic worlds.

Whip-smart and full of charm, the girls take whatever work comes their way (provided it pays cash), surviving on cheap “hot dogs, pizza, deli sandwiches, and tacos” by day, and oysters and salmon blinis necked at art world parties by night. The novel has been aptly described as both “a picaresque for the glamorous and broke”, and a “bildungsroman for the party girl”.

“Why should men have all the fun, while girls are warned to watch their language, their behaviour, their drinks?”

Happy Hour

is distinctive for portraying young women letting loose without the looming threat of moral or mortal punishment. The book opens with these thrillingly compulsive lines: “My mother always told me that to be a girl one must be especially clever. Before landing at JFK, I had three Bloody Marys and an extra piece of cake that fell apart in my mouth. A person should never take on a city with an empty stomach, and I am always hungry.”

This echoes Eileen Myles’ poem Peanut Butter, which opens: “I am always hungry / & wanting to have / sex. This is a fact”. Also voiced by a bold-spirited, voracious speaker, Myles’ poem is a high-velocity paean to appetite and pleasure: “Pleasure / as a means, / and then a / means again / with no ends / in sight. I am / absolutely in opposition / to all kinds of / goals. I have / no desire to know / where this, anything / is getting me.” This would not be out of place in Isa Epley’s diary: this is the Party Girl philosophy.

Granados’ book is as refreshing as the first sip of a martini on a searing summer’s night. Particularly so because it lands in a cultural moment dominated by a taste for disaffection and detachment. A number of novels published since 2015 (including Alexandra Kleeman’s You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine, Ling Ma’s Severance, Halle Butler’s The New Me

, and Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation) possess a kind of anhedonic quality: remote, benumbed and desensitised.

It’s not just books. In the contemporary moment, authors and artists are also revered for their detachment and asceticism. Publicity for Adrian Piper’s 2018 MoMA retrospective frequently mentioned that, by 1985, she abstained from alcohol, meat and sex. Marina Abramovic supposedly only ate vegetables while performing The Artist Is Present. Ottessa Moshfegh is said to have risen at five in the morning, had a banana and a cup of coffee and gone to the boxing gym for three hours before setting down to write her first novel. “She had become this kind of weapon,” Moshfegh’s agent said. “She seemed not to need anyone or anything.’

“Trying to have as much fun as possible seems to be one of the only good uses of my time. Life is short and parties are great”

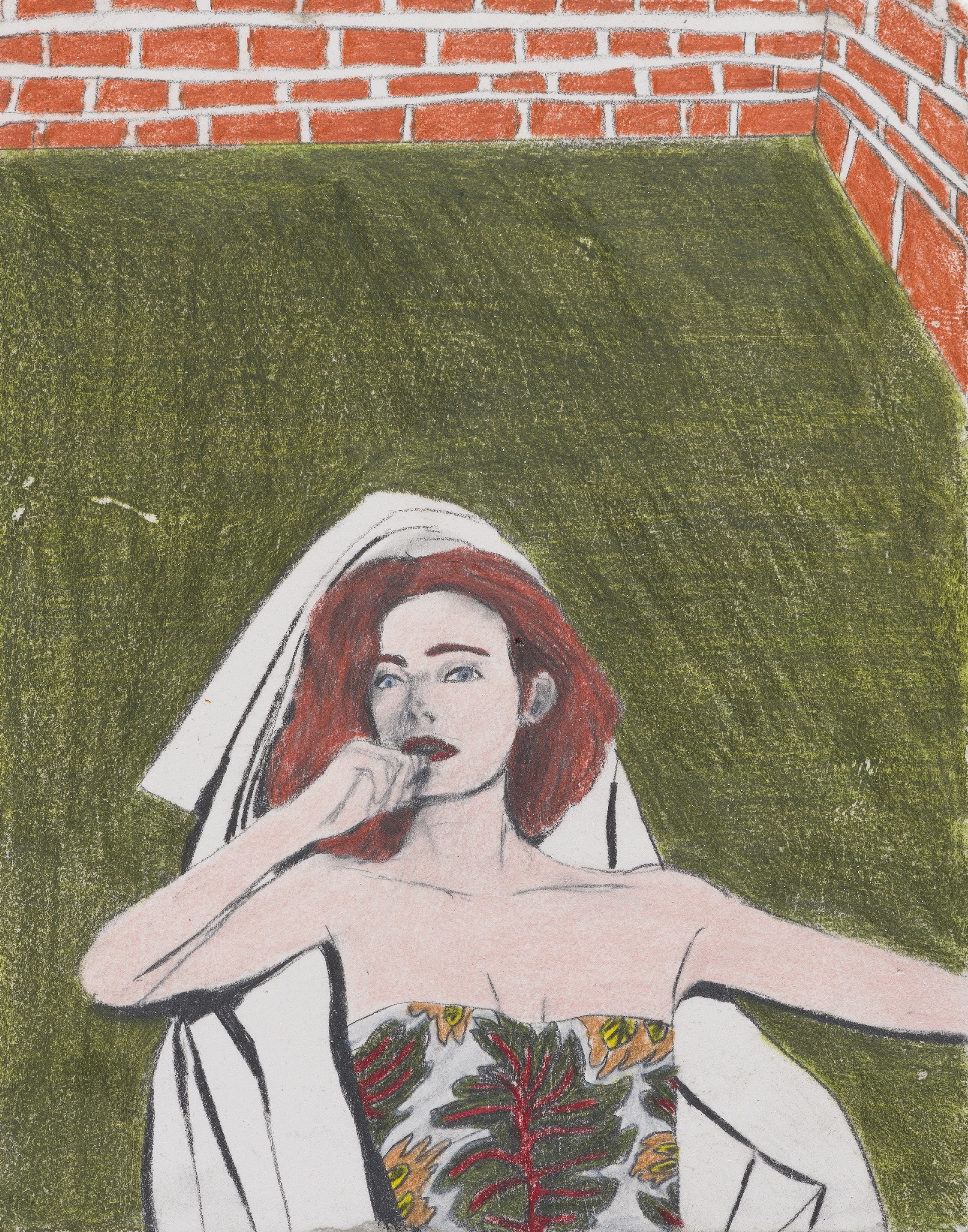

Last year, I realised I had been subconsciously gathering a moodboard of ‘serious women’, dispassionate women, and women in various states of collapse. Matisse’s women in rumpled silks; Pierre Boncompain’s women sprawled across mattresses; Marie Jacotey’s Lying on a Sunday, never getting up. I kept returning to a still from Chantal Akerman’s Les Rendez-vous d’Anna (1978) where Anna’s head is tilted so sharply on her pillow her neck appears broken, her food tray sloping into bed covers, untouched and reminiscent of prolonged hospital stays.

There was Susan Sontag smoking and looking disdainful. Dorothy Parker. Hannah Arendt smoking and looking disdainful. Deborah Nelson’s Tough Enough (2017), a book on ‘unsentimental women’ whose cast consists of Sontag, Arendt, Simone Weil, Mary McCarthy, Joan Didion, and Diane Arbus. Michelle Dean’s book Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion (2018), which recounts anecdotes from the same set, plus a handful of other ‘sharp’, ‘tough’, uncompromising women.

I now understand that in seeking out weapon-like women, I was trying to grasp a certain style of female intellectual, and of female creativity that is, paradoxically, both accepted, and read as rebellious precisely in relation to its rejection of stereotypically ‘feminine’ traits. What I wanted was to be taken seriously, and, consequently, I was drawn to women who refused to play nice, to smile or to put on a front.

“Granados’ book is as refreshing as the first sip of a martini on a searing summer’s night”

Yet what seemed to be required was a rejection of joy, and a repression of desire. What if I didn’t want to become a weapon? What if I don’t need anyone and anything, but simply want them? Truthfully, I can’t bear to leave my breakfast tray untouched, I want to devour every crumb. I am also always hungry. I want to have my cake and eat it, and have an extra piece too.

Granados stresses that “having fun and taking these things that tend to be cast aside as nothing serious is so important”. Suggesting that “people often don’t understand how important lightness is”, she argues that “the ability to fight for lightness is so much about how you enjoy life”. In a pandemic, of course, the importance of lightness, spontaneity and excitement is thrown into sharp relief. So surely now more than ever the light, free-spirited nature of the Party Girl is something to be celebrated?

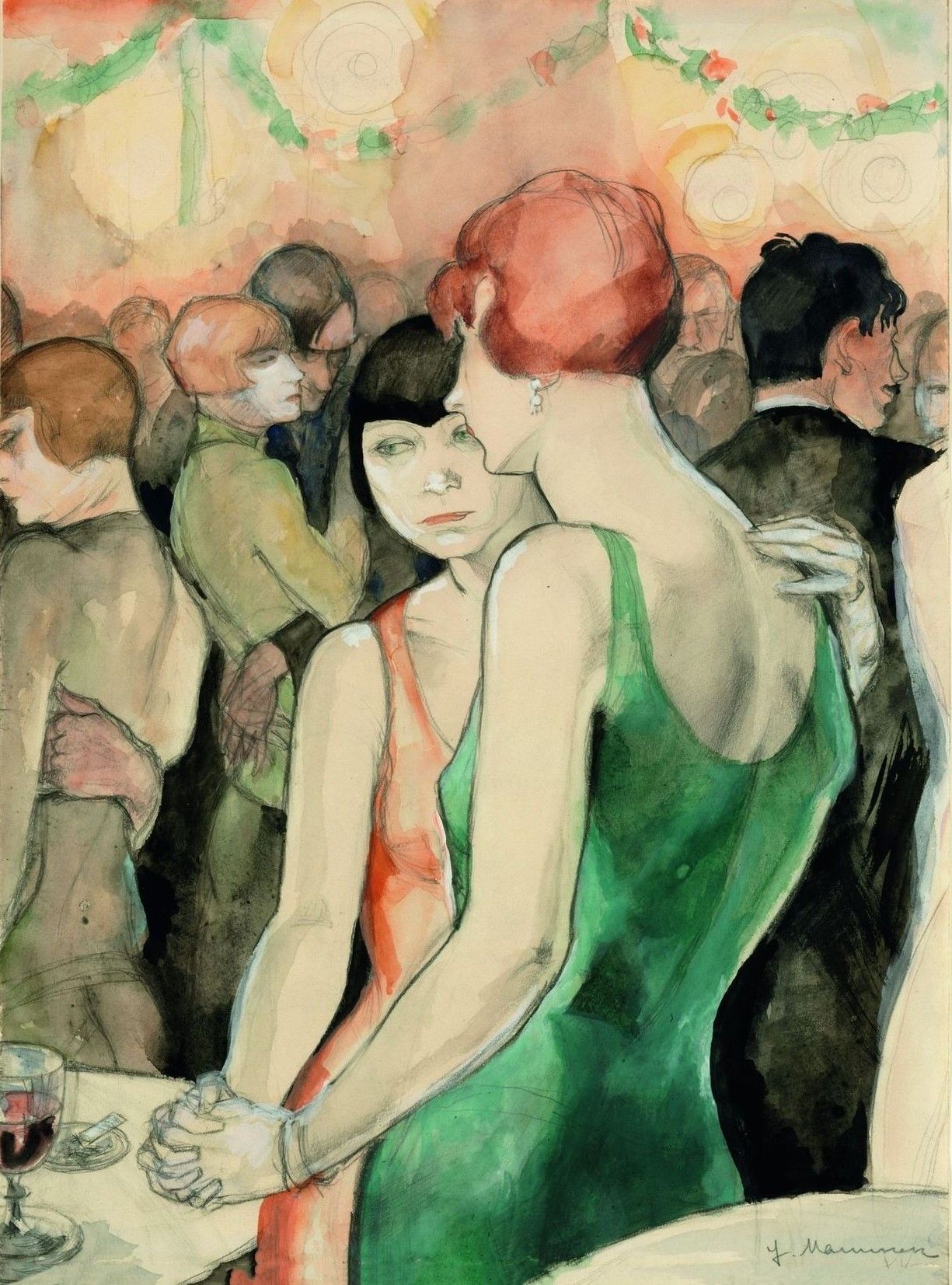

In this tentatively post-Covid world, enough with detachment and asceticism. I want less punishment and more parties. I want to collect different talismans. The women throwing their mouths and arms open in the centre of Faith Ringgold’s Jazz Stories. Jeanne Mamman’s Weimar women dancing. Anita Loos’ charming flappers in her book Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Zelda Sayre, before becoming the infamous Zelda Fitzgerald, writing in her high-school diary, “I ride boys’ motorcycles, chew gum, smoke in public, dance cheek to cheek, drink corn liquor and gin”.

“Now more than ever the light, free-spirited nature of the Party Girl is something to be celebrated?”

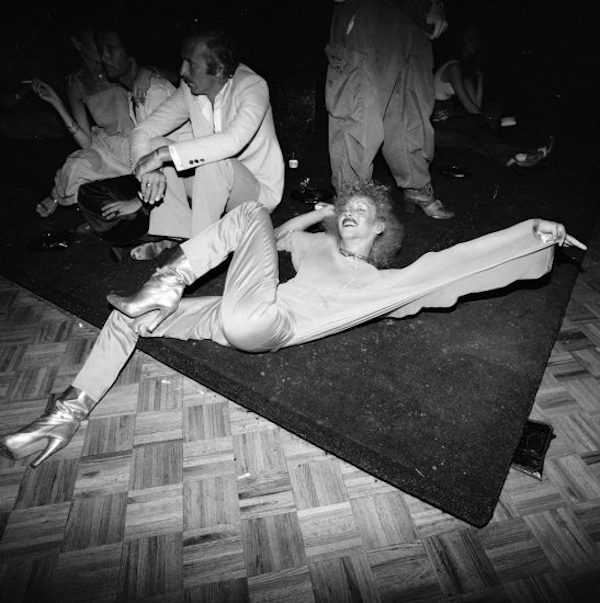

Bianca Jagger riding around Studio 54 on a white horse led by a naked man covered in gold glitter. Meryl Meisler photographing Studio 54’s hedonism, her partner in crime, Judi Jupiter, in tow. The electrifying fizz of Eve Babitz’ prose, and the thrill of her posing nude with Duchamp to get back at her married boyfriend, the curator of a Duchamp retrospective, who refused to invite Babitz to the opening party.

Like the speaker in Phoebe Stuckes’ poem Paris, “I want to be stinking drunk / in a restaurant eating bread from a basket, thinking of vintage Prada / and snow”. Pleasure as a means, and then a means again with no ends in sight.

Eloise Hendy is a writer and poet living in London