“This is a man’s world,” James Brown once sang, “But it wouldn’t be nothing without a woman or a girl.” It’s a song that splits opinion. Is it a charismatically performed display of chauvinism: one long list of man’s achievements, with women as compensation for all their hard work? Or an attempt to puncture the fragile male ego: a reminder that no matter how shiny the car or big the cheque, nothing matters without love? It certainly outlines a millennia-old gender imbalance where men make the world, and women live in it.

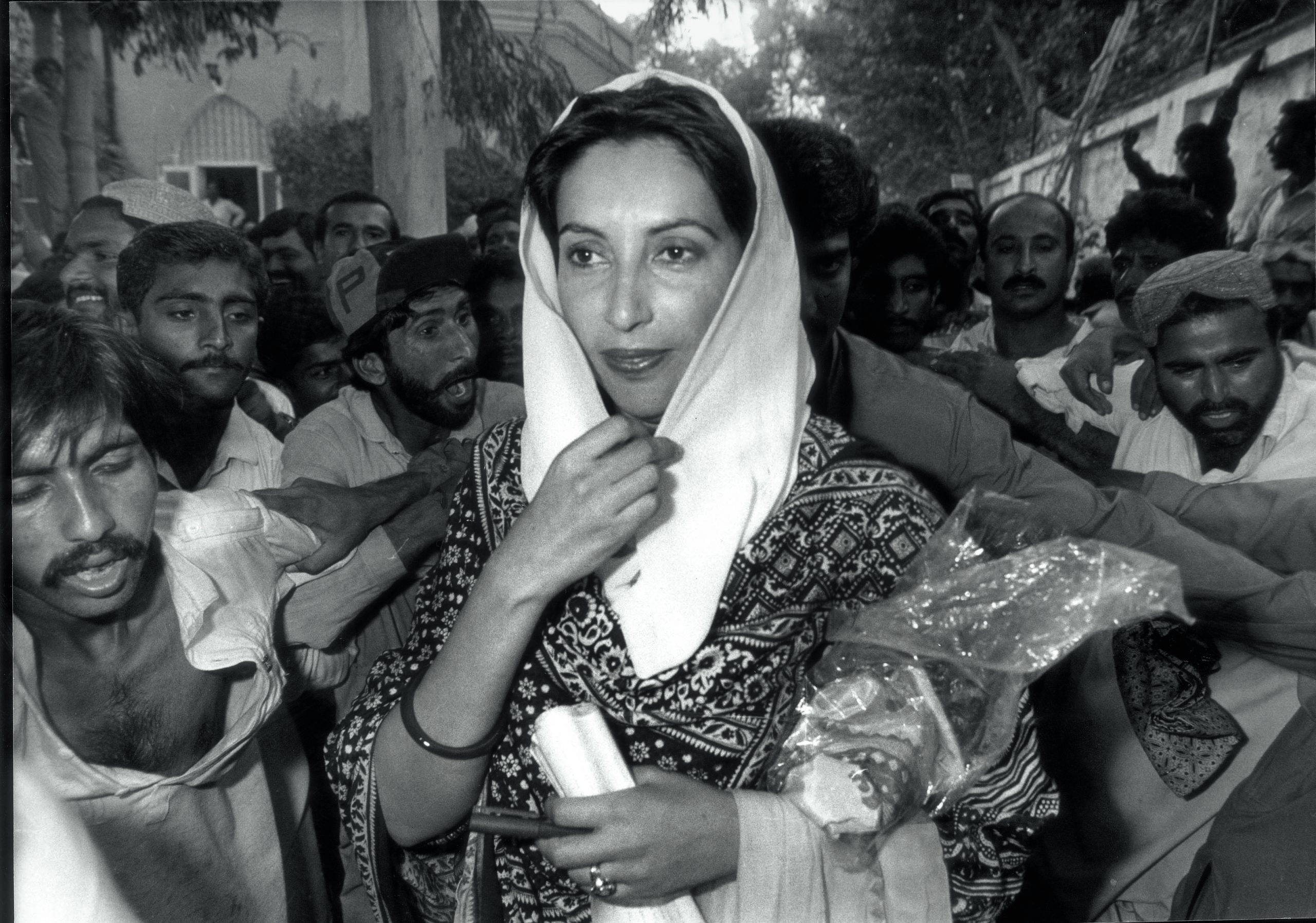

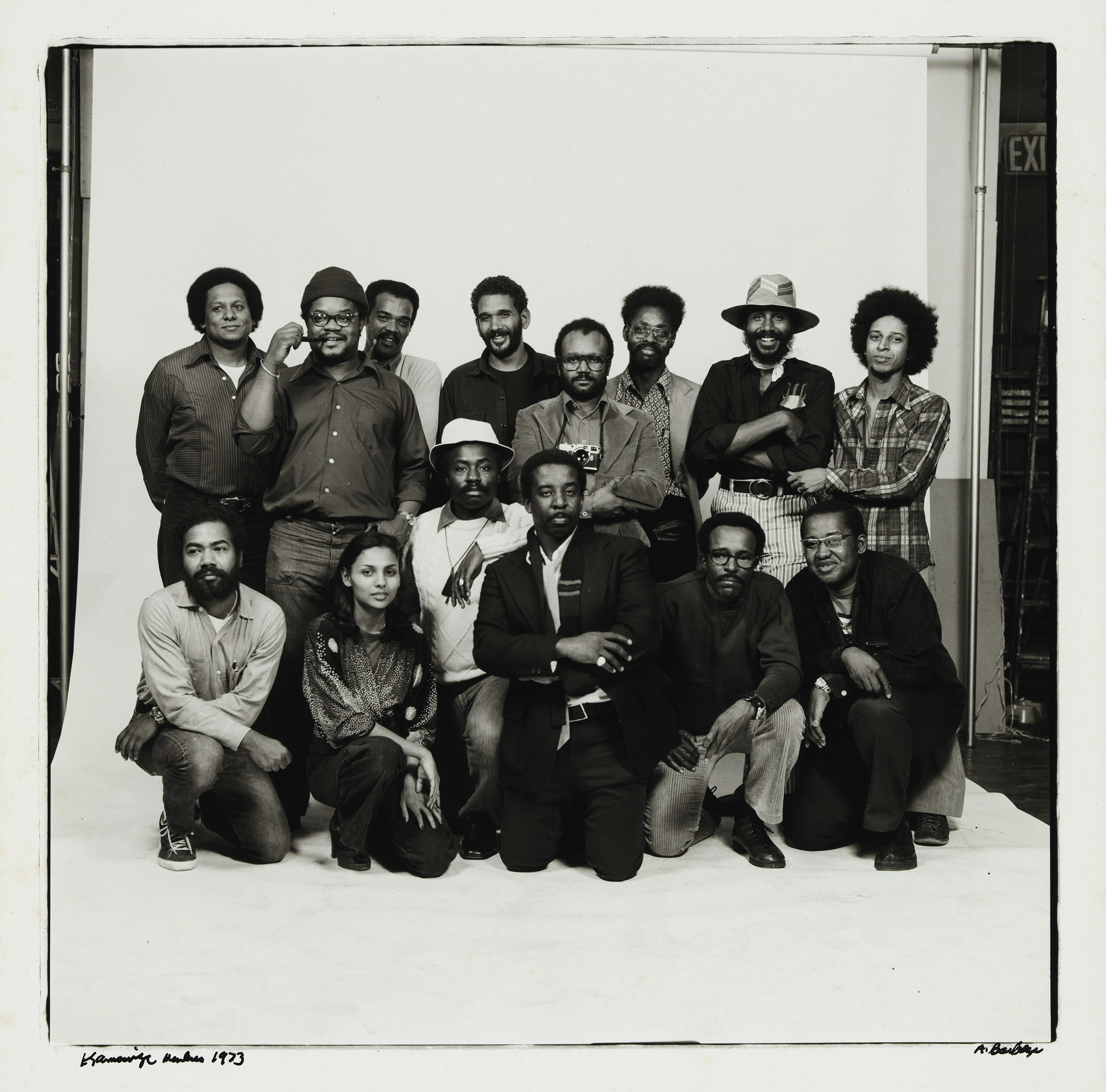

Author Immy Humes likens the process of browsing the photos in her new book The Only Woman to a game of “Where’s Waldo?” (or Wally, as the figure in the red-striped jumper is known in the UK). It’s a good comparison. In each image of people from a range of professions and backgrounds from 1860 to the present day, we are invited to locate the solitary woman among the men. Reading the book is to engage in the busy work of seeking.

Humes’ book is concerned with the women throughout history who have crossed the threshold into professional or social worlds in which they are overwhelmingly underrepresented. This is “a study of power as seen in one hundred photographs of groups of grown men… with only one single woman,” she writes. “Each photo offers forensic evidence of patriarchy on parade, along with all the other forces of domination.”

The project began from a place of idle curiosity. Humes, who is also a documentary maker and television producer, found herself fascinated by group portraits of artists: male, serious, largely dressed alike. The lone woman was often a remarkable presence: an exceptional (or merely honorary) attendee of the boys’ club.

Soon Humes widened her search. Every industry and sphere yielded something similar. Medicine, music, sports, politics, academia, journalism, engineering. From deep sea divers to sugar beet technologists, somewhere there was probably a photo featuring one figure set apart from her peers.

“From deep sea divers to sugar beet technologists, somewhere there was probably a photo featuring one figure set apart from her peers”

Humes is not painting a uniform portrait of femininity, or indeed, sexism. At a glance we might take these photos as one big paper of evidence on women’s historic exclusion from work and public life, but Humes remains attuned to the other questions these photos raise about varying balances of power. A fashion designer surrounded by naked male models occupies a different position to a secretary in a boardroom meeting or the sole female appointee to the American presidential cabinet. Hierarchies of race, class, and seniority play an equally present role too.

Humes attempts to create a loose taxonomy of these disparate figures. All are Only Women. Some are present because they are working in highly gendered careers (nurse, assistant, model). Others are there by dint of family or marriage (especially royalty). Several are affixed with special labels: First, Mascot, or Token. The Firsts are self-explanatory. They are pioneers in their field, from physicist and chemist Marie Curie to US politician Shirley Chisholm (who ran for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination in 1972), though when it comes to the latter Humes quotes documentary maker Shola Lynch on the dangers of “relegating Chisholm to a ‘first’” and turning her into an immortal icon, “thereby erasing the effort and guts it took to act out on her principles.”

“Humes’ book is concerned with the women who have crossed the threshold into worlds in which they are overwhelmingly underrepresented”

The Mascots

are there not for their own achievements but to cheer on the boys, a silent totem of femininity like the figurehead on a ship, bestowing good fortune with her incongruous presence. The Tokens are the visible nod towards inclusion that hides a vast apparatus of exclusion beneath.

Humes is a thoughtful writer. The accompanying texts do not feel like the rushed mini biographies that sometimes leave projects like these drifting around on the surface of feminist history, discarding the jetsam of nuance and complexity in favour of banal statements about progress. Not all of these women are savoury characters, or agitators for social equality. Plenty were happy with their outlying status, not only pulling up the drawbridge behind them but draining the moat too. Margaret Thatcher appears with the careful caveat that during her tenure “she only appointed one woman to her cabinet, never promoted any Tory women members of Parliament, and never championed so-called women’s issues”.

“The texts do not feel like the rushed mini biographies that sometimes leave projects like these drifting on the surface of feminist history”

To extend that question raised by Shola Lynch, what is there to be gained by affixing labels to these women, both known and unknown? And what is potentially lost? More broadly, what do we learn from a project like this?

Although this is a photography book, the images (a few notable exceptions aside) serve more as evidence of a principle than interesting individual works. It does feel somewhat scattered too. One can’t draw a line from Princess Di surrounded by paparazzi to Black Lives Matter protester Ieshia Evans standing calmly before two heavily armed, white police officers without erasing the vastly different circumstances surrounding them.

Perhaps this isn’t an exercise in line-drawing, but a collage composed of very disparate women. Hopefully it will introduce readers to some lesser-known figures too, such as chess champion Vera Menchik, educator and social worker Thyra J Edwards, Peruvian journalist Ángela Ramos, photographer Ming Smith, and Channel swimmer Ethel ‘Sunny’ Lowry.

The strength of this book really relies on their individual stories, as well as the wider visual narrative of women straying into the territory of men.

Rosalind Jana writes on fashion, art, culture, and travel. She has a column on photography and style for Magnum Photos

The Only Woman by Immy Humes is out on 3 August (Phaidon)