“Photographers are at work everywhere, looking at everything,” says Thomas Struth in a foreword to the newly released Civilization: The Way We Live Now, less a photobook than a big, beefy photo-tome. “Why not take a step back and try to take in the big picture?” The book, which accompanies a touring exhibition by the Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography—showing until next Saturday at Flowers Gallery in London—is an ambitious project, delving into the works of a wealth of photographers and analysing what they can tell us about human achievement in the twenty-first century. For the editors this also includes the 1990s when, they say, twenty-first century culture and civilization truly began—with the dawning of the Internet.

How we live; how we travel; where we live; how we interact. These are the subjects which interest the photographers represented here, who are from all over the world—or what Ewing refers to throughout the accompanying text as our “planetary civilization”. We have moved on from the days of Kenneth Clark’s art TV show and book Civilisation, which is highly dated while also remaining the basis for the way we look at much art via the mass media. Civilization: The Way We Live Now stands on the shoulders of that 1969 combo but also challenges its prescriptive mode.

What was once the traditional family unit has changed in many countries over the last few years. There are also literal changes in civilization anticipated as humans modify themselves with biohacking and alter their genes. In the digital age, everywhere is connected via fiber-optic cables, and photographers—once known for capturing the life of specific places and communities—are now are able “to travel widely, interested sometimes as much in an abstract concept of urbanism as in any one city’s particularities”.

“In what people call a “post-truth” world, is the documentation of reality affected? Does the old cliche still hold true—that the camera never lies?”

As such, the editors of the book and curators of the exhibition have found confluences between the work of photographers from wildly different environments. Ashley Gilbertson’s image of over 1000 US servicemen and women re-enlisting at a ceremony in Baghdad in 2008 is a stirring image of mass-humanity, cut through with a sense of foreboding. Noh Suntag’s Red House 1 #74 of 2005 achieves a similar, and similarly powerful, military tableaux for South Korea. Edward Burtynsky, in Manufacturing #17, captures workers at a chicken processing factory in China’s Dehui city who stand in rows. Their pink bodysuits and blue aprons, combined with the vastness of the operation, make them look like Rococo automatons, until you see one person occasionally looking to their neighbour, or occupied in thought, rather than engrossed in their work. A counterpoint might be Massimo Vitali’s CEAGESP São Paulo Analog Digital Diptych, 2012, which shows the freedom of a sprawling marketplace, and those who wander through it, choosing what to and what not to buy.

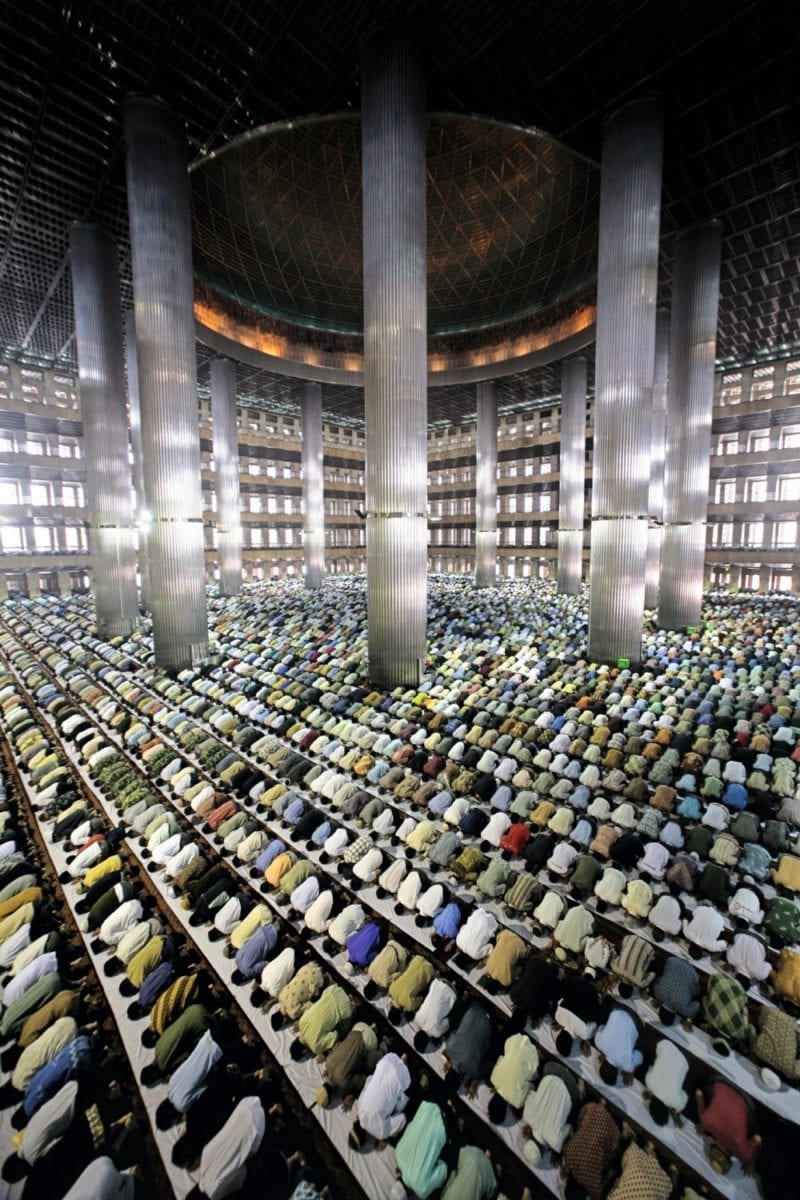

In photographs of cities in France, Korea and Iran, people stream like termite colonies over plazas and streets, either in profusion or sparely. Philippe Chancel’s aerial image of Dubai from his 2008 series Datazone looks like a fantasy world. But rather than the futuristic one you’d expect to be evoked by skyscrapers with desert sun bouncing off them, Chancel has somehow created a sort of elfin glade of fairytale pastness. Dubai’s modern towers become fragile cathedral spires. Irene Kung’s The Invisible City series does the same to Milan’s Torre Velasca and London’s Gherkin. Ahmad Zamroni makes the inside of a mosque in Jakarta, meanwhile, feel like a cavernous space ship. One of the most striking and sparse photographs in the book comes near the end: Simon Norfolk’s image of the Mare Nostrum supercomputer in Barcelona, which is built in a church. It evokes some sort of space-age museum, the ancient mixing with the modern.

The two most essential aspects of this project are declared precarious from the off: the art of photography using traditional film in the age of digital; and the subject it is capturing—people, who may destroy their own world just as they are moving towards finding ways to prolong their natural lives. Civilization might one day not even need humans, our cities governed by artificial intelligence. Also, in what people call a “post-truth” world, is the documentation of reality affected? Does the old cliche still hold true—that the camera never lies?

If the visuals are stunning, the text surrounding them—nonetheless thought-provoking—can seem too often a list of pronouncements about now, which offer very little in the way of meat or research, or speculations about the future. There is a hint of manifesto that exhausts. “We buy the latest must-have products—not to be left behind—only to find out the next day they’re outmoded; possession and embarrassment!”; “And yet, while it lasts, how heady it all is!” There are many exclamation marks and rhetorical flourishes. “What’s next? […] Driverless cars, trains, planes? Yawn. A robot mowing the lawn? We’ve already got one out there working now. Artificial intelligence? Already here.”

“There is no reason I can think of why some of the images in this book won’t be seen, one day, as having a similar resonance to Jeff Widener’s famous shot Unnamed Protester or Tank Man“

But the words aren’t the draw here, and were never supposed to be. Richard Wallbank’s photographs of butterflies he has genetically engineered himself are a brilliant curatorial touch. Raphaël Dallaporta’s 2004 Antipersonnel series makes war equipment like land mines into stark still lives in the style of Spanish painter Juan de Zurbarán. Big names have been brought into the project. Cindy Sherman’s 2008 series Society Portraits is great but possibly unnecessary here, where images from Amalia Ulman’s 2014 project Excellences & Perfections—in which the artist transformed herself into an Instagram star and garnered thousands of unironic followers—fits perfectly.

We could do with less images from others addressing the same theme of empty consumerism. There are only so many pictures of billboards you can look at, no matter how poignant and imposing, without colluding in the meretriciousness the project sets out merely to document.

- Left: Francesco Zizola, In the Same Boat, 2015. An overcrowded rubber dinghy sailed from the Libyan coast is approached by the MSF Bourbon Argos search and rescue ship. 26 August 2015 © Francesco Zizola / Noor Images; Right: Ahmad Zamroni, Muslims at Prayer, Jakarta, 2007 © Ahmad Zamroni

Civilization: The Way We Live Now is at its best when form meets function. A highlight is the photojournalism which itself is being squeezed by the death of newspapers and magazines. Francesco Zizola’s 2015 image of Libyan refugees, In the Same Boat, is powerful, as are Mauricio Lima’s images of fires burning in the Calais jungle in 2016, or Sergey Dolzhenko’s documentation of Ukrainian nationalist groups marching in 2017. Damon Winter supplies a brilliant shot of a US navy soldier having been injured by a landmine in Afghanistan in 2010. There is no reason I can think of why some of the images in this book won’t be seen, one day, as having a similar resonance to Jeff Widener’s famous shot Unnamed Protester or Tank Man, in which a Chinese civilian can be seen standing in front of a line of tanks following the crushing of the Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing, 1989.

But this won’t be the case for future images the more the medium is squeezed. In the same year as Damon Winter captured his image of a US soldier sustaining landmine wounds, Will Steacy took a photograph of complementary poignance: the offices of the Philadelphia Inquirer, which had come to occupy one floor when it used to overrun a whole building in the nineties. What will the next edition of such an undertaking look like, and who will be the journalists, artists and documentarians to fill it?

Civilization: The Way We Live Now, Edited by William A Ewing and Holly Roussell

Published by Thames & Hudson

Buy this book