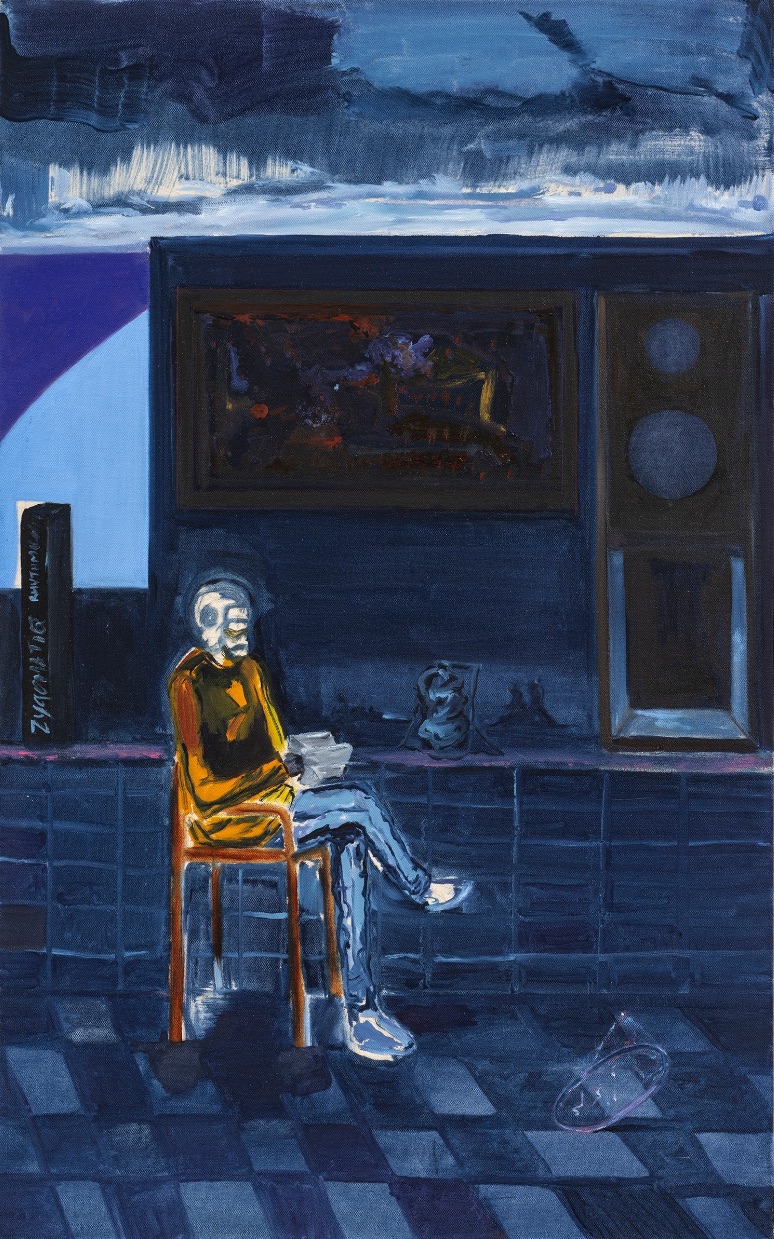

Andrew Pierre Hart Brings the Sights and Sounds of the Neighborhood for New Commissions with Whitechapel Gallery

In the middle of our conversation, Andrew Pierre Hart shared with me that he had previously worked with a bassoonist who had synesthesia (the ability to see specific colours when you hear sounds.) During their collaborations, she said that his voice emitted the colours blue and purple without ever having seen his paintings that are made of those exact same colours. Seeing colour in sound is an interesting phenomenon, and it cuts directly to the bone, especially for an artist like Hart, whose musical background as both a DJ and producer is highly influential within his art practice. Hart is known for employing techniques such as improvisation, spontaneity and ‘deep listening’ to create his works, and it feels that when you spend time in Hart’s artistry, you can see that rhythm flows right out of the confines of his canvas.

“I was born in London. And growing up–North, East, South, West… It was just London. I’m not into the regional thing. Because it separates us.”

Just this weekend, Hart opened an exhibition at London’s Whitechapel gallery entitled “Bio-Data Flows and Other Rhythms – A Local Story”, in which he utilizes these techniques to explore the history and people who make up the neighbourhood of Whitechapel. On view are all new works commissioned specifically for the gallery, featuring a site-specific mural, six new oil paintings, a bamboo sculpture, a new sound composition and a film shot in the streets around the neighborhood. It’s hard to pin down the exact references for these works because the inspirations are as diverse as Whitechapel itself, from the Gurunsi people in Nigeria, who influence the geometric shapes in the mural, to the flags of the various immigrants who have made new lives in Whitechapel to the famous Bangladeshi workers that are the heart of Brick Lane. Hart has taken in all cultures, and the result is a beautiful tribute to the special people who make up this special neighbourhood of London.

Shaquille Heath: Congratulations on your opening! How do you feel now that people can see it?

Andrew Pierre Hart: Yes, feeling good. Lots of people, families, some kids were just in the galleries sketching the mural that I had made. We’re doing a performance tomorrow, so there’s no resting. I can’t fully reflect just yet; maybe after the weekend. But yeah, I think the atmosphere within the show is good, and viewers have been enjoying it. I think they feel relaxed enough to be able to come in and sit down and draw. Yeah, a family came in to explore art with their kids. They sat as a group, maybe four kids and two mothers, and were sketching and drawing from the mural. It was perfect! The other thing was it was locals from the area, which is even more important.

SH: I’m sure that was really amazing to see. So these works are all new pieces commissioned specifically for Whitechapel, correct? What was the conversation that y’all were having prior to their creation?

APH: Yes! So the Director Gilane Tawadros was very much like, do whatever you want to do. I said, “Are there any guidelines you want me to lean into?” And she was like, do whatever you want. But I think she also knew that I was going to be responding locally and responding to what’s been happening in Whitechapel. And I think that’s kind of the ethos of the gallery. It was carte blanche, and that’s what they’ve allowed me to do. Very free. Very open.

SH: Yeah, focusing on Whitechapel is very in ethos. Are you from the area? Or have you spent a lot of time there?

APH: I’m not from the area. But I was born in London. And growing up–North, East, South, West… It was just London. I’m not into the regional thing. There’s always been north, south, and east, but I don’t buy into it. Because it separates us, it’s the same; no matter if you’re from a certain demographic or background, things are the same. They say this thing, “I’m good in any hood”– It’s kind of that. So I’m trying to disrupt some of that, “Oh, he’s not from the area. But actually, he really researched and connected things from the area together.” Yeah, I don’t like this regional separation. I also understand the local artists and have worked with people locally. Spoke with people locally. Mural painters, people who study in the area. Obviously, that is a consideration.

“That’s why it’s called “bio-data” rather than statistics. Information that’s natural. Through looking, through engaging, through walking.”

SH: Tell me about some of the research you’ve done on the area and how it inspired the artworks that people can see on view now.

APH: One of them was actually walking around and just looking. So Brick Lane (a street in the area) is very famous for Bangladeshi and Indian restaurants. I just got talking to one of the guys because he was wearing all these Dolce & Gabbana labels, and we got to talking about the fabrics being pressed in India and the fact that he considers it cheap material because they just get them out of the back of the warehouses. Also, there are ongoing histories around race and the Bangladeshi community moving to different areas. There was a Bangladeshi boy who was attacked and, stabbed and died in 1978, and then there was a riot after that.

So I’m just talking about some of the quite poignant and prominent histories of Whitechapel. And then, how does it become information? That’s why it’s called “bio-data” rather than statistics. Information that’s natural. Through looking, through engaging, through walking. And how can we visualize such information? I started to design this idea of using a motif that I’ve done before, partaking in flags of all the people who come through Whitechapel. It’s Russian Jews, Polish Jews, Irish, Scottish, Dutch, Caribbean. Somalians are the newest demographic here. But all of the colours relating to the flags are in the work and then kind of built around that story of migration. Whitechapel was one of the first places that immigrants came to. They came to Whitechapel because of the water, the location, the accessibility to accommodation, and to work.

So then, how does that look? I don’t want it just to be information written down and very didactic. I want it to have the kind of aesthetic that you can look at, and it just looks interesting as a visual kind of response. And then add the layers. For example, it’s also used as a teaching tool to school children because it points out all the flags and also tells them the story and the shape of the map of the area. The kind of aerial view of Whitechapel.

SH: You have a background in music as a DJ and a producer. This is probably maybe like a chicken and egg kind of a question… but do you remember what came to fruition first? Was it your music or your artwork?

APH: I’d say…music…I don’t know! Because I went to do my A levels, but the environment and what we were actually doing in terms of art– drawing, freeline left hand… I just found it really boring. So I kind of checked out and went to party. And that’s what I actually did.

But by doing that, I always had art in mind. So when I was going through it, I was always looking at lights and at people. The colours and how it all played, because it was just like this big spectacle. We were kind of always listening to hip hop, rear, groove. But then there was this alternative thing, which was rave music. And yeah, so I went into that. And that’s what influenced me into getting into music.

But I always had my love for art. So, no matter what I do, I draw. Biomaterials. Make some stuff. Then, I developed this idea to produce music. I started a record label. The label is called Deepart. And it’s all one word; it’s not “deep art.” It’s just one word. It really was a weird way of thinking because although it was this music, there was a story. There’s a story about empowerment. So there was always a sense of that.

“It really was a weird way of thinking, because although it was this music, there was a story. There’s a story about empowerment. So there was always a sense of that.”

SH: Speaking of music and sound, when you look at your paintings, can you hear them? Does this correlate with the soundscapes that accompany your exhibitions?

APH: I can’t hear them. But what happens with sound is it either likes or it doesn’t, basically. There’s stuff that sits with my paintings, and I know that they work together. And there’s other music that… they just can’t work together. I’m always making paintings with a particular kind of sound. Soulful sound. Because it contains so many different types of music, it has to have a kind of soul. Has to have a round bass in there. Some funk in there. Yeah, I think that’s what shapes it. It’s always trying to communicate something.

I think a synesthetic person might be able to hear them, depending on what their cross-modalities are. It also might be this kind of subconscious sound or noise. I don’t know. If we can listen to music and see colour, why can’t it be the other way around, as you just proposed? Why can’t we look at the colour and hear the sound? So maybe we don’t hear it as a tone. Or we might hear it in some sort of a feeling. Maybe the feeling is the hearing. When you feel something, maybe that’s the hearing. Something to explore… I work with a synesthetic bassoonist. Maybe some people can hear it because she says my voice is the same colour as my paintings. She’d never seen my paintings and said that my voice is blue and purple.

SH: Oh my god! That’s so interesting!

APH: Yeah, it kind of freaked me out.

Written by Shaquille Heath

Andrew Pierre Hart: Bio-Data Flows and Other Rhythms – A Local Story on view at Whitechapel Gallery through 7 July 2024

FIND OUT MORE