Pushing through the boundaries of the traditional idea of the artist, Goshka Macuga’s practice also involves her taking on the roles of archivist, critic, philosopher, historian and curator. For her latest project in Milan, she went under the skin of the Fondazione Prada. ‘I quite like the idea of being a detective,’ she tells Muriel Zagha.

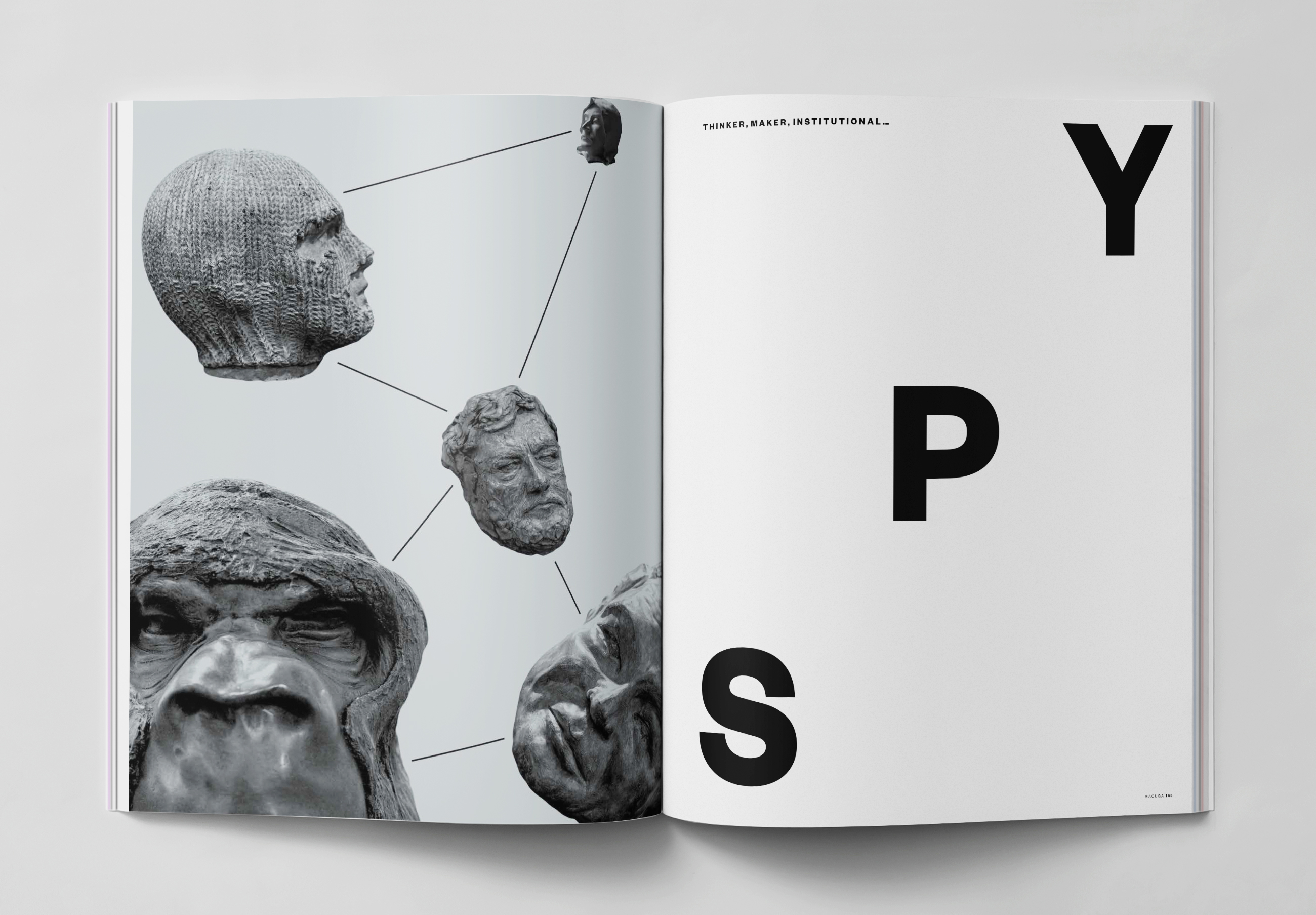

Goshka Macuga’s work embraces a great variety of media—sculpture, drawing, painting, film, photography, tapestry—and takes the form of complex installations into which she incorporates archive materials, museum artifacts, and new objects produced by herself or other artists. Working all at once like a cultural archaeologist and a detective, Macuga weaves all these materials into a narrative that focuses on institutional histories, proposing unconventional associative readings of their social and political contexts.

When we meet in her East London studio, she has just returned from the opening of her new show in Milan, To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll, perhaps her most ambitious to date, which examines the idea of the end of humanity.

You researched, curated and designed To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll. How did the project come about?

The new Fondazione Prada space in Milan opened its doors to the public in May 2015. It was a new beginning for this institution and I thought it might be interesting to address the question of the end on this occasion, but in a broader context. Scientists and thinkers have been trying to define humanity for centuries, but we are now at a stage where the questioning has turned towards whether we are post-human or if, perhaps, we are reaching the end of our existence.

This raises many ecological issues, but there’s also a historical strand of human thought, starting from Greek philosophers, that reflects on our concern with the idea of the end. We humans have always feared this, but we have perhaps never come so close to it. The project involved four or five months of research before making or producing any artworks, as well as looking at the collection of the Fondazione Prada. The Fondazione had recently bought a studiolo—a late fifteenth-century panelled study room, with marquetry inlay, originally designed in northern Italy to reflect its owner’s intellectual and social status. Historically, studioli were also a place in which to study the arts of memory and rhetoric, which were used in the composition of political was seen as creating artificial memory, and so it has close links with today’s technology.

These themes of rhetoric and memory echo throughout the exhibition. The centrepiece of the show, To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll, is an android performing a speech that is an amalgamation of sections from famous speeches by Martin Luther King, Freud, Einstein, many people who are significant to me, and that in different ways address the idea of the end. The android introduces himself as a collector of human speech, speaking at a time when humans no longer exist, so it’s a kind of post-human proposition of how our knowledge might survive. The robot is, conceptually, closely connected to the studiolo, where a performer undertakes readings of significant texts in Esperanto.

Esperanto is the only purpose-made language: it was constructed in the hope of unifying understanding and communication and then collapsed. When I came to this country in 1989 there were still centres where you could learn Esperanto, like the one in Holland Park. Now it’s an extinct idea.

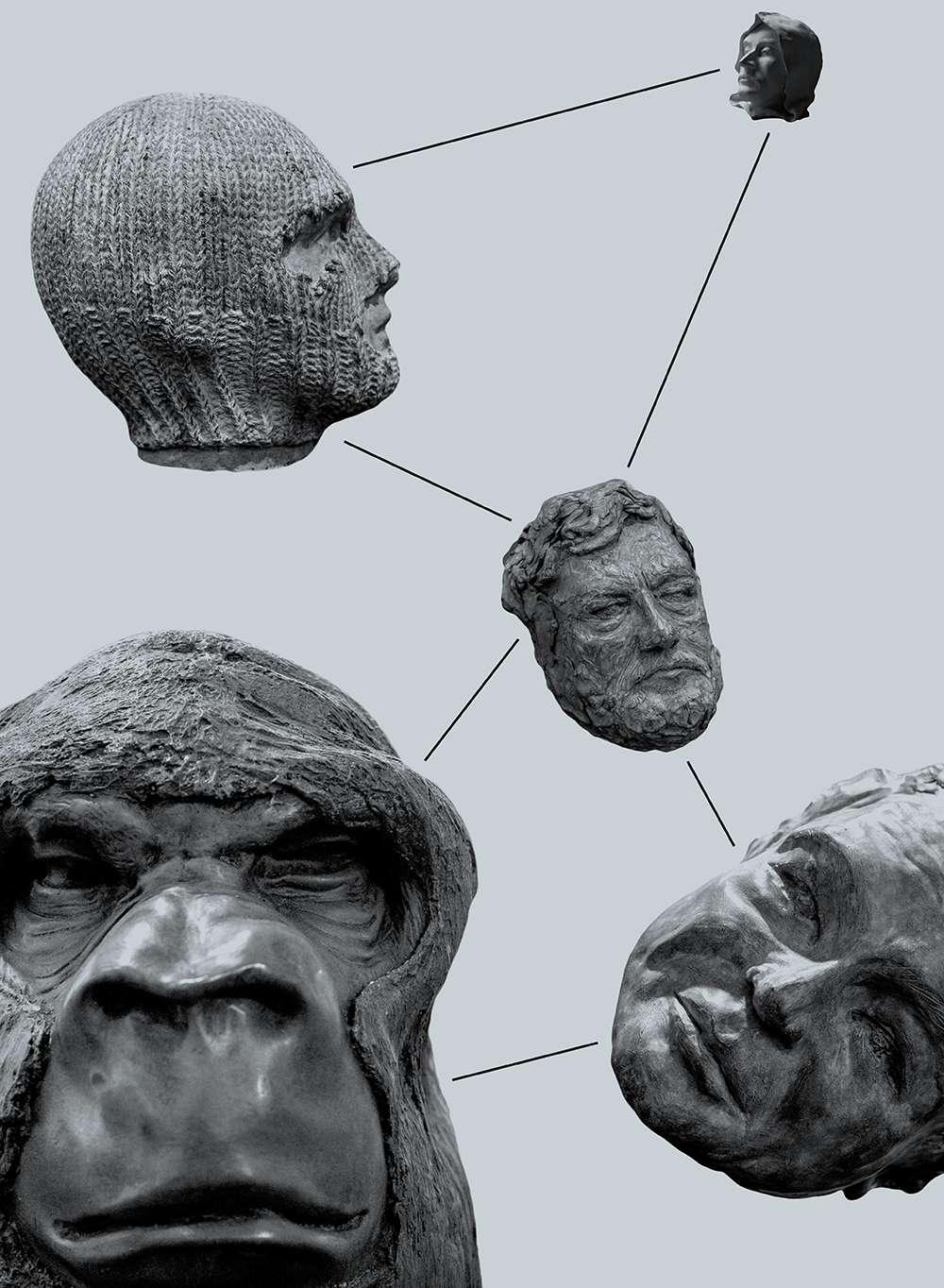

You also collaborated with Patrick Tresset on a series of drawings.

The installation Before the Beginning and After the End consists of five large scrolls containing drawings made by Patrick’s computer system Paul-n, laid across industrial tables together with objects loaned from different museums. Each table displays a narrative of sorts, which evolves from table to table: from Adam and Eve to the creation of di erent religious systems, diagrams relating to Hermetic philosophers, the beginnings of medicine, the theories of Einstein, etc. We borrowed 3,000-year-old pieces from the Egyptian department in the Louvre, for example, as well as very contemporary works. On the sixth and last table we have robots, designed by Patrick, drawing the ending of the narrative in real time. This project is vast, with a lot of details and connections between things and ideas.

Is research an important part of your practice?

For me the research part is even more important than the actual making of art. Of course, I love being an artist, but I like to have access to different practices from what one would have normally in the studio. It’s something that really excites me. On this occasion I really went into technology, a completely new thing for me. Normally a whole project, all the research and the production of the work, would take me six months, up to a year, but here, because of the scale of it, it lasted for a year and a half. That’s why I feel so ‘radioactive’ today. And the worst thing is that I’m already thinking what to do next.

Somebody made this really cynical comment to me at the opening: ‘If this is about the end, is this your last project?’ And of course through the whole period when I was working on this, because it was so much a question of life and death to finish it in time, I thought: ‘Maybe this will be the last project that I ever make.’ When I took the flight from London [to install the show], it was one of those days when the weather wasn’t very good, and I thought: ‘ok, this is the perfect moment to die. The project would happen anyway and I would be free from my pre-show anxiety.’ So I was having all these fantasies, but even though the plane took off in a turbulent way, we landed without any drama. And then I had another two weeks of torture installing the show and being really stressed.

How do you feel about incorporating the work of others into your own?

Collaboration has been a major aspect of much of my working life. In the nineties, when we were studying at Goldsmiths, lots of us would do exhibitions in our homes and studios. One exhibition would involve a number of people, who would invite more people into the next one and then into the next, and those that stayed on would evolve within the work and add to it, so we had a very accumulated context. And I was fascinated with how the context of a domestic environment reflects on the work, how the work fits into it, how people produce something in relationship to each other, and how this culminates in a reading of the work collectively.

I scrutinized all of this and then embraced it as a strategy: dealing with the dynamic of context. By then I was making some pieces of my own art in a bigger environment, borrowing things such as artworks and objects. It was a big operation but on a very small budget. Later on I was invited to create these works in gallery spaces, so I did a show at the Transmission Gallery in Glasgow [Homeless Furniture, 2002], I went to Sweden to present Cave [Kunstakuten, Stockholm, 2000], then I made work for Fundacja Galerii Foksal [Untitled, Warsaw, Poland, 2002].

From then on, the work became much more complicated: I wasn’t only working with friends, I was also borrowing pieces from collections, I was doing research in different museums. The high point of this was the exhibition I did in 2006 in Liverpool [Sleep of Ulro, A-Foundation], where I really pushed myself to explore how I could develop my practice and really exercise my working methodologies. Sleep of Ulro involved many collaborations with other artists as well as relationships with different collectors and museums.

The involvement of others means that you end up doing things that you might not have done by yourself. That is certainly the case with Patrick Tresset, because he has an amazing knowledge of robotics and a very interesting approach to how technology can question human creativity.

Is your desire and ability to collaborate with other artists in any way related to having grown up in communist Poland? Is it a sort of art communism?

This is a tricky question: usually at the end of a project, everything looks good and we are all happy, but this is not necessarily how the process works! Artists like to have control over their work and how it’s shown.They are open to experiments to see how things can be shifted slightly, but in the end you are the leader and the tyrant. In the last few years I have been going to cern in Geneva and speaking with the scientists there: I wanted to learn more about quantum physics. It’s a great pleasure to speak to these people: they know a lot about the arts, about music as well as science. It’s been a really enjoyable process partly because there was no outcome, no pressure to deliver. It became more magical because it was about thought and not matter. It’s all about chemistry and physics, it’s like falling in love. Collaborative processes are tricky, because I think that it’s most interesting when it’s not conditioned.

You have a polymorphous, omnivorous attitude to using different media. Is it a question of chemistry within you? Do the questions you ask yourself dictate the media, or do you happen to be playing with tapestry, photography, Photoshop, and then see certain preoccupations graft themselves onto that?

I don’t really have a great romantic connection to any medium. I’ll perhaps work with a specific medium for a few years, then I’ll stop and move on to something else. The first tapestry I made was Plus Ultra, for the 53rd Venice Biennale. It referred to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who commissioned many tapestries as a form of propaganda in order to further his political and military status. Plus ultra, meaning ‘further beyond’, was Charles’s motto, and reflects a significant attitude of that time towards the world, which is part of the history of colonization. This motto was often shown on a banner wrapped around two pillars, the Pillars of Hercules [which flank the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar], which represented the edge of the ‘known world’. It is this image of an S-shaped banner around two pillars that the dollar sign is said to represent.

Plus Ultra explores how these histories intersect with our contemporary political scene, and tapestry felt like the most appropriate medium to incorporate all of these ideas. Around the same time, I was working on a project at the Whitechapel, The Nature of the Beast. I was looking into a substitute of Guernica for the exhibition and I came across the tapestry reproduction that was hanging at the un and was covered up during Colin Powell’s speech promoting the invasion of Iraq. The significance of this act drew me into a closer consideration of this medium. As well as its historical relevance, tapestry was a good solution for me because I could produce quite large works and move them fairly easily: Le Corbusier refers to tapestries as ‘nomadic murals’. Plus of course they are so close to propaganda art, so this was a good medium to address my relationship to politics.

What about your approach as an archivist?

It is very striking how,when you are invited by an institution to do something, the first thing you do is go under the skin of the institution by looking into its archive. This feels like an appropriate response to the way we live now. We are surrounded by information, and whole new fields of study teach people how to deal with data. So if you are interested in finding some sort of truth, you need access to sources and documents that are more subjective than what is already mediated in history books or art-history books. But I also find statistics fascinating. I go to the archives but I also visit MIT websites and try to learn about machine learning and the different ways that data is processed.

What interests me is how you extract the truth from what has been registered as such, if it’s not something that you have witnessed directly. This has obvious links to my past and how we experienced history in Poland or in any part of the Eastern European bloc, which is a totally different relationship to history than in the rest of Europe. When my nephew goes to learn his Polish history at school it will not be the same history that I learned. History is a constructed narrative and this of course lends itself easily to manipulation. In my work, I rarely use material that hasn’t been revealed before or that is my own discovery; instead I try to decontextualize the material that I come across. I’m not so much of a detective—even though I quite like the idea of being a detective. But if you are invited to do an exhibition in an institution, that institution and its history are your context, and even if you didn’t go to their archive, some people could contextualize your work within the history of this institution. Many American institutions are founded on private money that often wasn’t made in politically neutral ways. Nobody chooses to talk about these nuances anymore because that’s how the whole culture has been built, but it does matter to know this stuff: I like to know it.

You like to know whom you’re getting into bed with?

Yes—the embedded phenomenon! All the information that we’ve had access to regarding recent wars is not material collected in an objective way. When journalists wrote about the Vietnam War it was subjective recollections for the most part, today it’s embedded photographers who are entitled to have access to zones of conflict, and they cannot witness everything that goes on. So I kind of embed myself as well, but for a different reason than war journalists do.

You first came to London in 1989. How different was it from your native Poland?

I actually wanted to go and study icon restoration in Russia, but I wasn’t accepted. I came to London because one of my friends was here. This was before the Berlin Wall collapsed. Then it just went from one thing to another, I did a foundation course, then went to Saint Martins, then straight to Goldsmiths. Meanwhile Poland was changing massively: you’d go back and the names of streets wouldn’t be the same. There was a massive growth of the art scene there, and many conflicts between artists, institutions and the public. It was a crazy time, when things were really on high alert. In some ways I was upset that I was missing out on it but at the same time I really enjoyed the whole progression of how I was working here.

Since 2006, I have been working non-stop on different big projects: it’s been ten years of consistent development. Almost every time I get invited to do something I do a new thing, and only on few occasions do I reshow groups of works. It’s a pretty hardcore way of working. There is often an insecurity about making site-specific work and wondering if it will translate anywhere else. Actually it totally does. For example, a big project I did in Poland, which looked at the time of my absence—from 1989 to the present—and the issues of the public censoring culture, was all in Polish but was shown in Chicago, then in Vienna. People have different approaches to it but they totally get it: they understand the language of monumental art, the language of bureaucracy, even if they can’t read the text.

‘To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll’ runs at the Fondazione Prada, Milan until 19 June.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 27