If you’ve passed through Piccadilly Circus lately, you might have noticed something different. Soft Opening, a home for collaborative shows with artists, is the brainchild of curator Antonia Marsh who has spent five years exhibiting itinerantly between the UK and the US. “It’s such a relief not to have to constantly relearn the infrastructure of a gallery space, and now I finally get to work one-on-one with artists in a much more intimate way.” Taking over a vitrine-like spot underground, Soft Opening also benefits from the half a million or so people who pass through the station every day. The second exhibition at Soft Opening brings two young NYC-based artists, Willie Stewart and Grace Ahlbom, to London to explore the visual vernacular and reimagine the role of subcultures. I spoke with both artists.

Soft Opening isn’t a regular gallery space: what did you think when Antonia approached you about this show and how have you worked with the space—both physically and considering the way viewers will see the work?

Willie Stewart: As an artist, I am interested in spaces on the margin of the everyday. These types of outsider places have some type of architectural structure that defies utilitarian logic, and it’s this resistance that opens up the opportunity for intervention.

Grace Ahlbom: After Antonia showed me her space I was mostly excited because of how different it was from a typical white cube gallery. Of course, most of the time when you see works in a space as public as the subway it will be government commissioned blockbuster artworks or cultural monuments. While there’s something different about showing in the underground, there’s also a history tied to it, and I think it was really interesting to play with that. The viewer’s access to the space is also different, while we were trying to come up with titles for the show, I kept thinking about how the window is the only way to see into the gallery space. It reminds me a lot of window shopping.

WS: When I think about a space on the edge of a path, I think about the possibility of seeing without looking, and what I mean by this is that by being exposed to something visually in your periphery it ingrains itself unconsciously. You are left with a memory that still has the potential for discovery, and when actually looking, the effect is different when analyzing it—because it is strangely familiar. So they become two different registers of understanding; the real, what you are actually looking at, and the remembered, from your unconscious experience.

What was it like working together on this show?

WS: Working with a group of people on a project is always incredible. The way we recalibrate and align ourselves together to create a type of group brain, which fills the gaps related to experience, helping to mitigate a direction towards a larger intent of understanding what everyone involved cares about without having to be from the same place.

GA: I’m thrilled to see we are now showing together nearly two years after first meeting each other. Willie and I met in New York while we were both studying at art school. Willie was doing his BFA at The Cooper Union and I was doing mine at the Pratt Institute. It was a month before our graduations and we were introduced by a mutual friend who saw a link between our works. We both have the same love for the visual vernacular of American culture and its individualism.

You both address the fetishization of various aspects of American culture in your work, can you tell me more about your interests?

GA: I think we approach the idea of America within a kind of fetish, because America has been delivered to us as fantasy. My most recent work wasn’t shot in the States, it was interesting to see the ways my subjects, whether it’s the Parisian cowboy or grunge Icelander, identified and embodied themselves through American pop culture. Mostly because they projected the American lifestyle they see through Hollywood and online, as most do. There’s a degree of projection on both sides. On one end, they are already performing to the world and bring that with them when I’m shooting, on the other end, I’m also framing that performance within my own lens and projecting my ideas onto them.

“I think we all approach the idea of America within a kind of fetish, because America has been delivered to us as fantasy.”

WS: The apparatus of the Ouija board is very simple as an object, a flat board marked with the letters of the alphabet, numbers, the words “yes”, “no” and “goodbye”. Modes of automatic writing like that of the Ouija board goes back to 1100AD, in historical accounts of the Song dynasty in China. Although it is the rise of spiritualism in the Victorian era, and the creation of the modern talking board in America in the late-1880s by Elijah Bond, then made famous by William Fuld (an employee of Bond) which cements it in our culture. In 1991 all intellectual property of the Ouija board was sold to Parker Brothers, an American toy and game manufacturer, which re-inscribes the purpose of the object outside of the sincere hope of having a connection between the Ouija board and the user, but as an object situated within the irony of teenage mischief.

I am fascinated by an object that can move through nine hundred years, and morph through modes of use related to the truly sincere and ironic. This morphing gives me hope that there is potential for it to change again into something I can’t even imagine today. It is this illegibility of the future that makes me want to create new objects, by virtue of thinking nine hundred years into the future and speculating what something can become.

Speaking of which, you deal with the sometimes nefarious and often mystical pull of objects; how do each of you feel about consumerism?

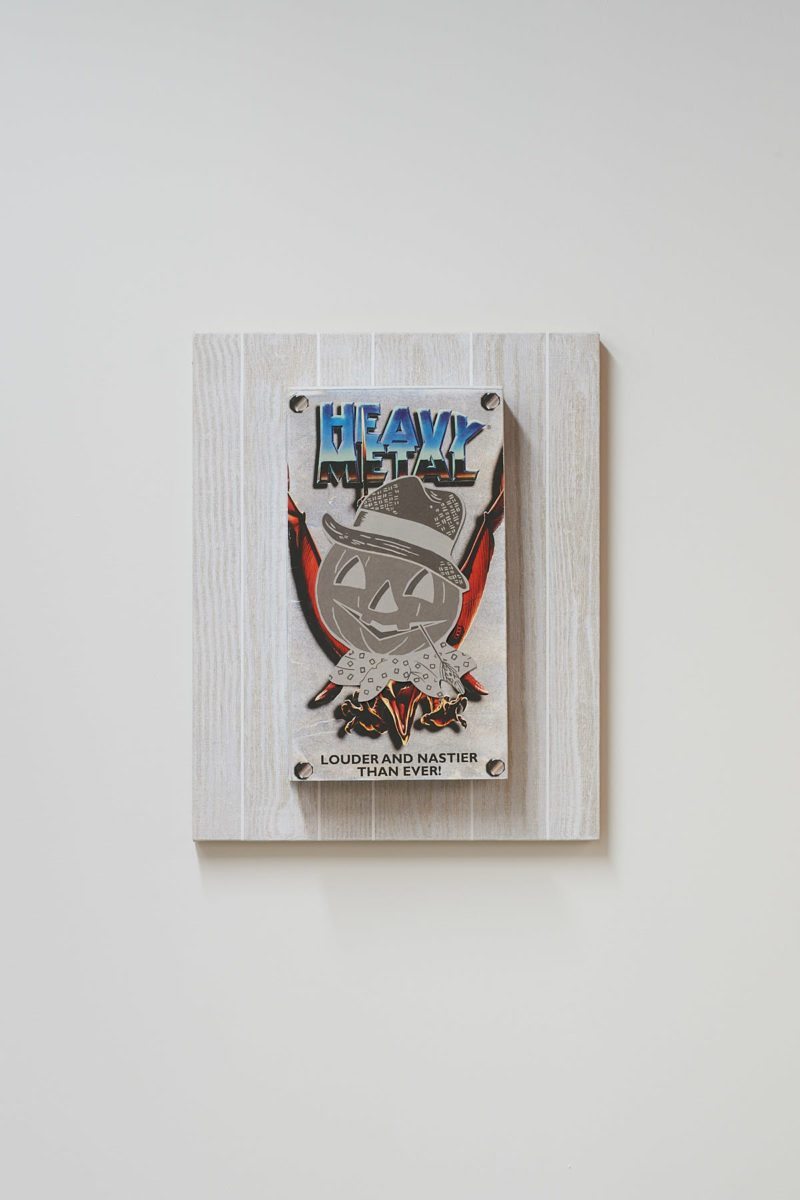

WS: When I was a kid there were magazines ads for mail-order music clubs, like Columbia House and BMG. These ads would be anchored by a big headline that would say something like, “12 HOT hits for a COOL penny”, and the page would be populated with a grid of over one hundred album covers, about half a centimeter in size each, and I would study these intently. What the advertisements were proposing was that you could have twelve cassette tapes for a penny, and you could choose from records like Soundgarden’s Superunknown, Michael Jackson’s Dangerous, Terence Trent D’arby’s Introducing the Hardline According to Terence Trent D’Arby, and Kick by INXS.

I filled out the order form based on what the images gave back to me based on my own taste and subjectivity at that exact moment. After about four weeks my twelve cassette tapes arrived in a small brown shipping box. What I learned from those twelve tapes is that all songs are written in the past, but we listen to them in the future, even if you listen to a track on the day it is released—a distance we are willing to accept.

We don’t think much about the primary, secondary and tertiary processes a cassette tape goes through before we listen to it. However, owning cassette tapes gives us a starting point to investigate the processes they are made from, something we should do with everything we own to understand what is hidden in the banality of its parts.

GA: I started working on this work while on a trip to Norway in the summer, when I stumbled into a record shop that jump-started my curiosity in the fanaticism of the black metal scene. I’ve always been drawn to fan culture, relics, shrines and their relationship to consumerism and boredom. The shop’s basement served as a museum of artifacts where fanatics visit the original meeting place for many emerging Norwegian black metal bands during the 1990s. Not dissimilar to my own basement, which serves not only as an archive of my adolescence, but the fantasy these objects seemed to hold for me at the time. Consumerism is already changing as more toy, book and music stores digitize and exist on screen, distancing themselves from actual objects that age and transform through time. In the record shop, the walls were overwhelmingly lined from floor to ceiling with thousands of records, t-shirts, CDs and props from photo shoots. I was fascinated by the way cultural obsession comes to create landscapes and monuments that occupy and manifest into a tangible space.

You’re both based in NYC. What’s it like working as an artist there at the moment?

GA: While I’m based out of New York, and produce all of my work out of there, I haven’t been there in quite a few months because I have been living at Antonia’s house [in London] doing a residency.

WS: New York City is steeped in deep histories of art and music, and as a scene, it has been nomadic, which has allowed it the privilege of influencing many different neighborhoods in the city. I grew up in Tennessee, not Brooklyn, but through stories of the city, I felt like I belonged there before I got there.

“A black leather jacket can be all you need to exemplify forty-five years of an idea related to individualism”

I once read an article about when the Ramones played the Roundhouse in the mid-seventies. Every British punk band that mattered was there: The Clash, The Sex Pistols, The Damned, The Pretenders… and while The Ramones were hanging out backstage no one would approach them. Accounts of the night claimed that Johnny Rotten was terrified that the Ramones were going to beat him up. I have always found this interesting because stylistically as punks the Ramones are really minimal, and were less interested in fitting in. There is something about the speed of New York City that creates an overall personal minimalism that produces unique ways of creating that keeps me utterly inspired by it. A black leather jacket can be all you need to exemplify forty-five years of an idea related to individualism.

Installation views: Theo Christelis, all other images courtesy the artists and Soft Opening