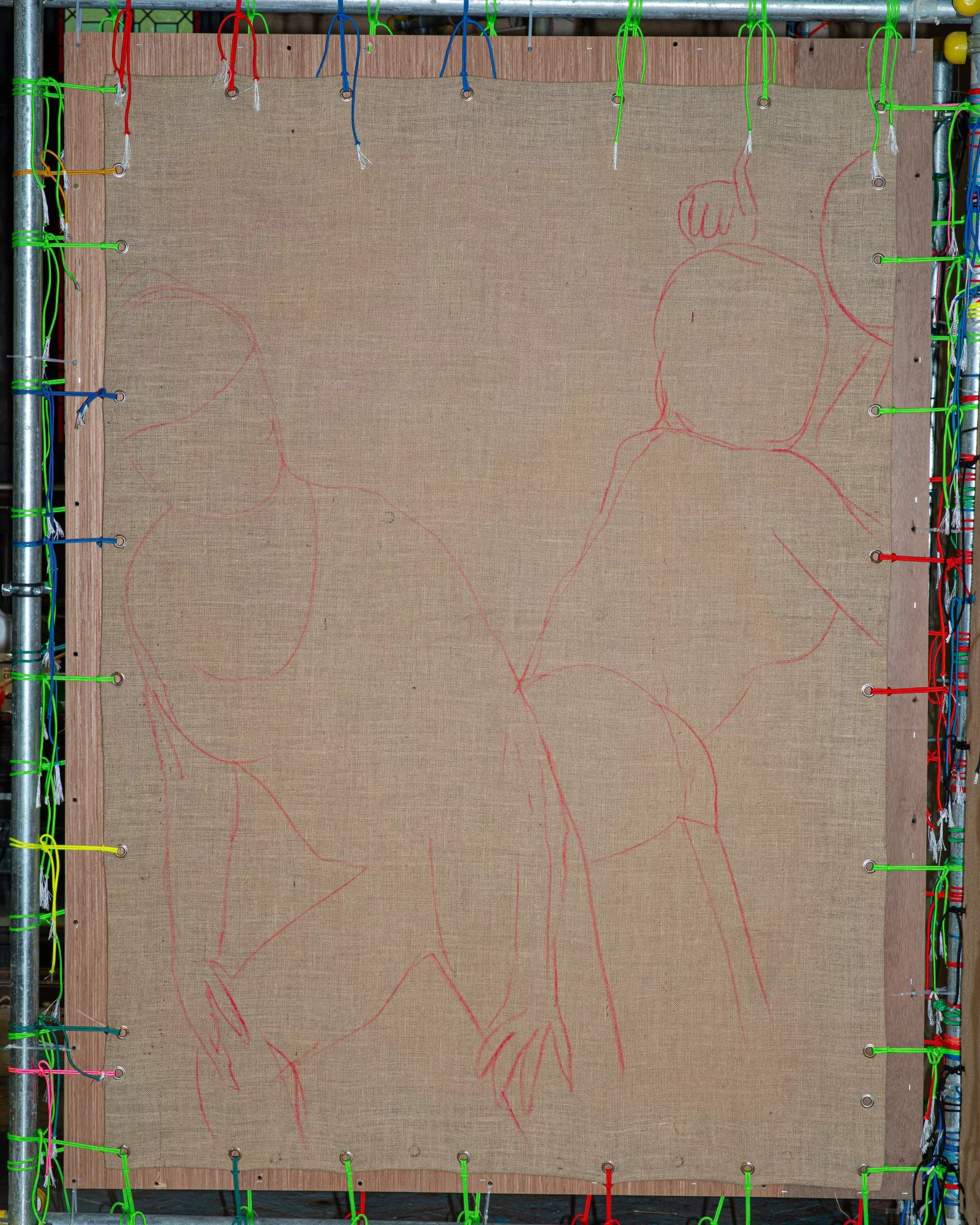

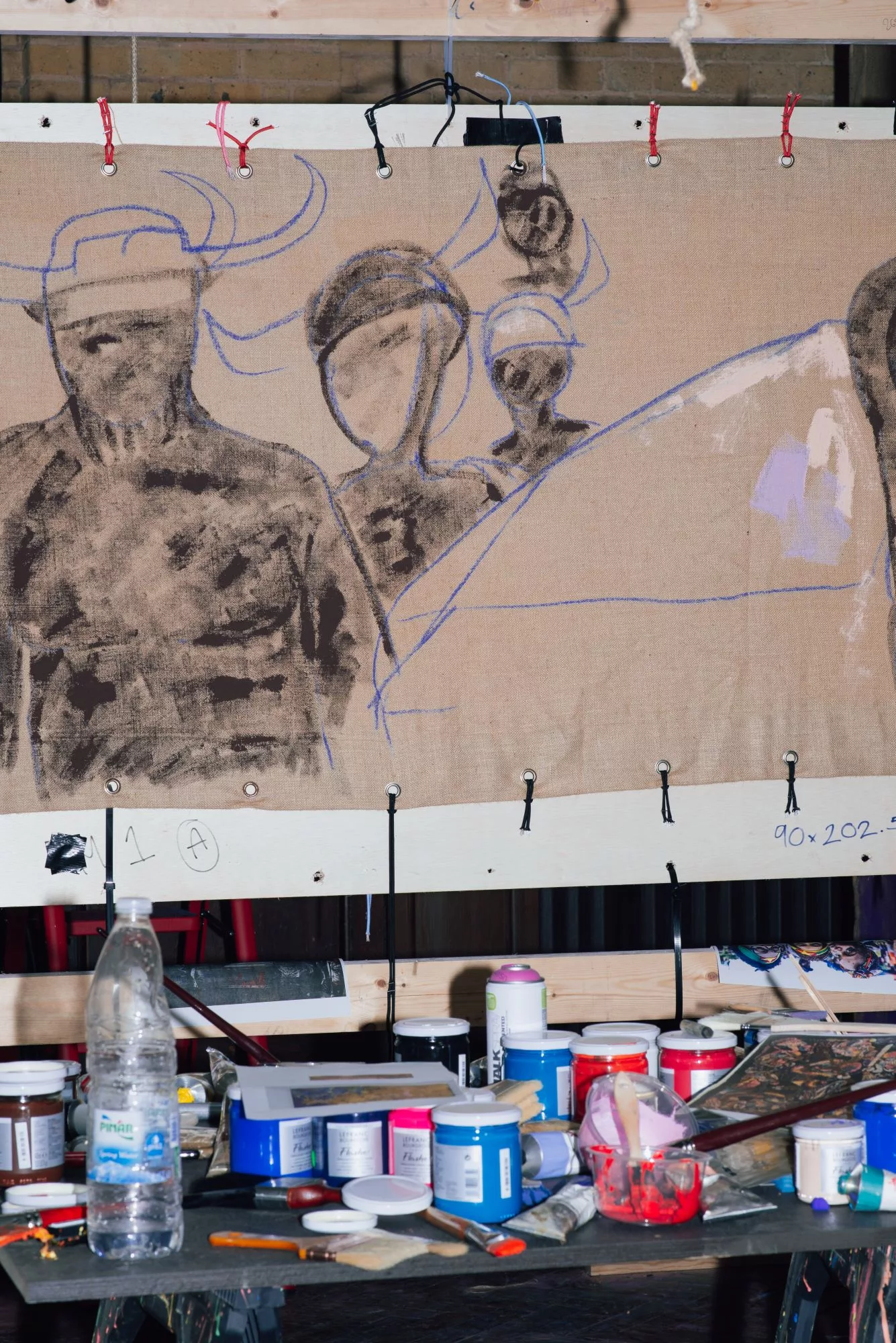

Alvaro Barrington’s East End studio, housed in the historic site of England’s first free school, is something to behold. Spread across two buildings, the space showcases an unorthodox mix of his preferred mediums and tools: paint, concrete, yarn, hessian, glass, neon lights, milk crates, snare drums, and brooms. In his neo-Jacobean assembly hall, music fills the air; a series of half-finished paintings, characterised by bright block colours and painted on burlap, are on display. It’s an unusual choice of canvas, but Barrington has never been an artist to play it safe.

Born in Venezuela to a Haitian father and a Grenadian mother, he grew up in the Caribbean and Brooklyn before settling in East London. Unlike many working-class immigrants who face hostility, Barrington tells me that he believes in ‘the ability to be seen in a place, and that lets you know you belong there somehow. One of the narratives I have about myself is that I come from a history of working-class immigrants, but I also have the privilege of growing up in a culture of hip-hop and reggae in New York City. That always meant that home became a couple of things to me.’ It’s this idea of home – lost, found, remembered, and reimagined – that remains a core focus of his work; it seems only fitting, then, that Barrington would be drawn to a Whitechapel, a historically immigrant neighbourhood, to set up his multi-purpose art space.

Walking around his studio, it became clear to me that intense commitment to painting means that personal and political questions are inseparable from his work. Barrington’s fusion of different artistic styles and cultural references speaks to an artist grappling with the fundamental issues of identity, memory, and what art can convey. Drawing inspiration from figures as wide-ranging as Cy Twombly, Paul Klee, Louise Bourgeois and Robert Rauschenberg, he creates a vibrant, eclectic mix that reflects his broad interests and playful approach to art history. Silhouetted figures – people dancing, reclining, revelling – are rendered with a playful candour, combining tightly controlled compositions with exuberant candour.

It’s this kind of fervid sensibility that Barrington hopes to bring to his upcoming Tate Britain commission, GRACE, his largest presentation yet, debuting in the museum’s Duveen Galleries. A deeply personal tribute to the women who shaped his life and artistic vision, the installation centres on three key figures: his grandmother Frederica, his close friend Samantha, and his mother Emelda. ‘The first part is about my Grandma,’ he shares with me. ‘We lived in a small shack in Grenada, where the rain hitting the corrugated roof was like a soundtrack. It was always a place of safety and love. I wanted an installation that allowed you to feel the texture of my grandma’s house.’ For GRACE, Barrington recreates this in the South Duveen gallery with a suspended corrugated steel roof, rattan seats, plastic quilts containing embroidered postcards, and the sound of rain mixed with newly commissioned tracks.

Music, a cornerstone of his creative process, energises his work with exultant colour and movement – even after only a quick glance at his vast body of work, it’s hard to deny the totemic influence that artists like Wu Tang Clan and Biggie Smalls have had on Barrington’s practice. ‘I try to capture the essence of music within my painting because it’s a kind of blueprint for me of what makes good art. Tupac is probably the greatest artist in my imagination. They’re North Stars for me,’ he explains. ‘As a painter, Western culture has contributed incredible amounts of innovation to painting, like pointillism and Cubism. But equally, the same could be true for music and black culture – think about jazz, hip-hop, disco, funk. Innovation in Black music has been immense.’ Central to GRACE is Barrington’s considered exploration of care, community, and Black culture – namely those from his childhood in Grenada and Brooklyn with the fervent energy of the carnival culture. The central space features a 3-metre tall aluminium sculpture of a carnival dancer, inspired by and made with Samantha. Adorned with pretty mas jewellery by L’ENCHANTEUR, a costume by Jawara Alleyne, and nails by Mica Hendriks, the figure emboldens that sense of Caribbean vibrancy. Paintings of old mas characters and carnival revellers stretch across scaffold structures, with sunrise and sunset paintings above, redolent of the J’ouvert tradition.

Profoundly influenced by the matriarchal West Indian community he grew up in, Barrington’s art is also a homage to the underappreciated labour of Black women. ‘Although most of my work is about my mom or my grandma, who passed away, but also the network of women who took me in after her passing,’ he notes. In GRACE’s final space, a stained-glass window casts light onto a boarded-up corner kiosk in reference to the police brutality faced by Black communities in the US. But it’s as much a celebration of kinship too, and the unwavering love felt by Black mothers for their children. Here, church pews covered in plastic recall the protective gestures of Barrington’s grandmother. As he explains, explains, ‘My mom got pregnant at 17, and my grandma took us in without judgement. Covering furniture in plastic was her way of saying, “Every time you come back, you have a home.”’

Near the end of our interview, I ask Barrington about how he manages to balance personal narrative with broader social and political commentary in his work. He’s a lucid talker, deftly moving between his childhood and broader cultural issues with the kind of ease that makes clear his art’s potential as a site for personal catharsis as well as its engagement with collective memory and social critique. However, how Barrington manages to distil all these ideas into one installation — or even a single canvas in some cases — remained a mystery.

After I finish talking, Barrington asks if he can read me some lyrics from Tupac’s ‘Keep Ya Head Up’. ‘Sure,’ I say, and laugh. He takes a deep breath and begins, ‘I wonder why we take from our women. Why we rape our women, do we hate our women? I think it’s time to kill for our women. Time to heal our women, be real to our women. And if we don’t we’ll have a race of babies, that will hate the ladies that make the babies. And since a man can’t make one, he has no right to tell a woman when and where to create one. So will the real men get up?’

Then, after a brief moment of silence, Barrington says, ‘And that’s a whole world there. In the lyrics, you could talk about reproductive rights. You could talk about police brutality. You could talk about all these systemic issues, but he’s just talking to the community and it’s from a personal place, you know? I have lyrics tattooed on my body because of it. I think for me, art is always about the personal. I never start from a political perspective. I’ve never liked it when I feel like artists were just preaching to me. Art is supposed to be the honest reality of a person’s life. For me, the deepest art has always been just about being political. All art I love is political. All art I love is personal, from the American AbEx painters to the Jewish immigrants, trying to figure out how to survive and how to be seen as human beings. It’s all very, very personal.’

Barrington takes another pause, smiles, and tells me, ‘It’s the only way I know how to make art.’

Written by Katie Tobin