There isn’t a bow-peep frock in sight when I meet Grayson Perry at the Victoria Miro Gallery. Instead, he’s dressed in the standard gear of the successful artist: ubiquitous white T-shirt, jeans and some rather snazzy tortoise shell glasses. Known to many as that bloke in a dress who won the Turner prize for his outré pots with their explicit scenes of sadomasochism, bondage and transvestism, in his day-to-day male persona without the glitter eye shadow and lipstick, he has a strong, nearly good-looking face. It is only the longish hair that gives any clue to his alternative life as Clare, when he then styles it into a blond bob.

After his successful show at the British Museum, The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman, for which he raided the museum’s archives extracting rare treasures that he then juxtaposed with his own artwork to create not only a personal take on world history, but what he calls ‘a journey through my mind’, he has recently acquired a wider audience, beyond the confines of the art world, with his witty, insightful series for Channel 4: All in the Best Possible Taste. In this he examined the British class system, along with the subtle complexities of signs and signifiers that define them. These included a torch song singer in a working men’s club, aspirational yummy mummy cup cakes and stolid middle class William Morris wall paper. A night out in drag, drenched in spray tan, with the girls of Sunderland was followed by a social bash among the ‘nobs’.

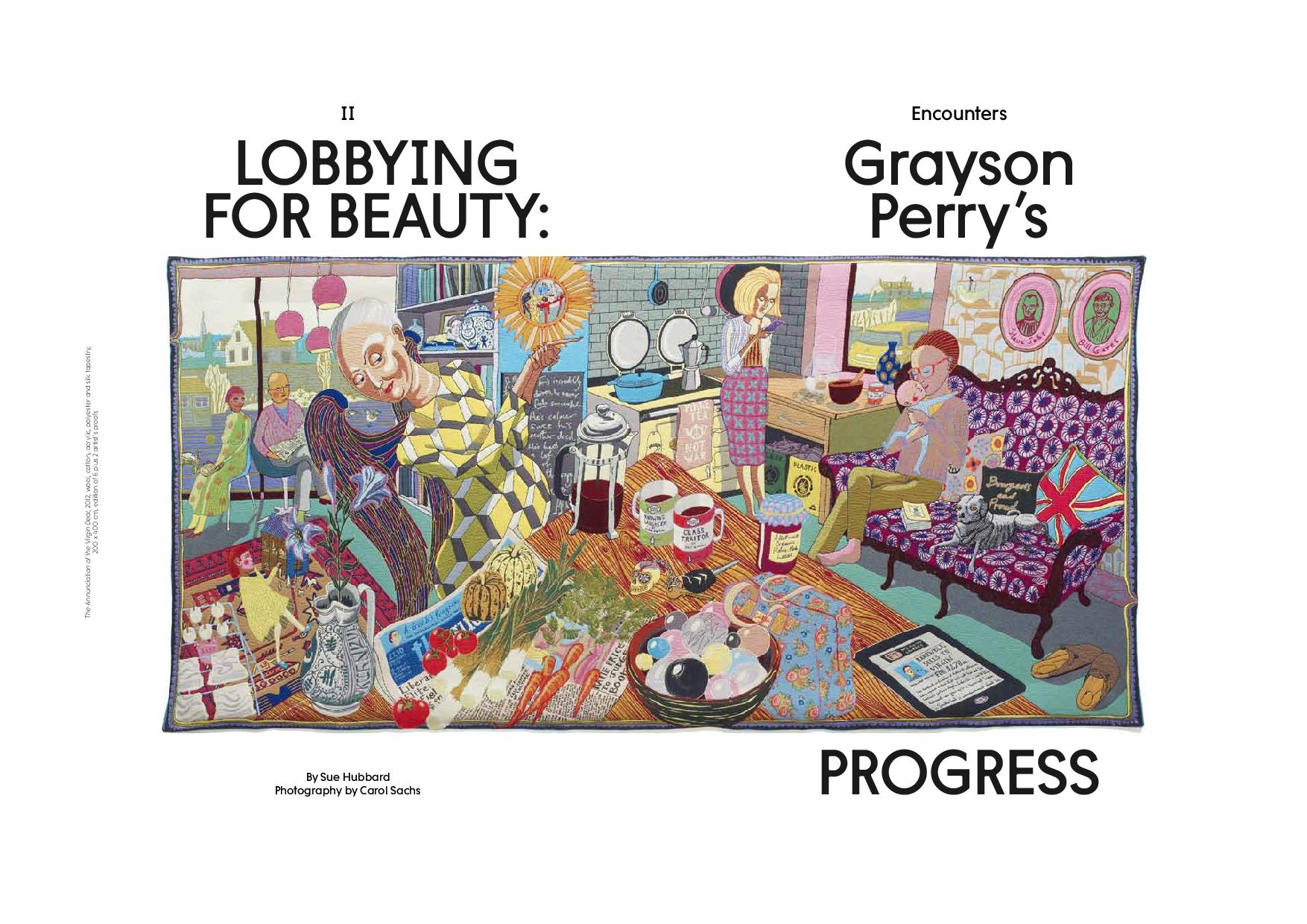

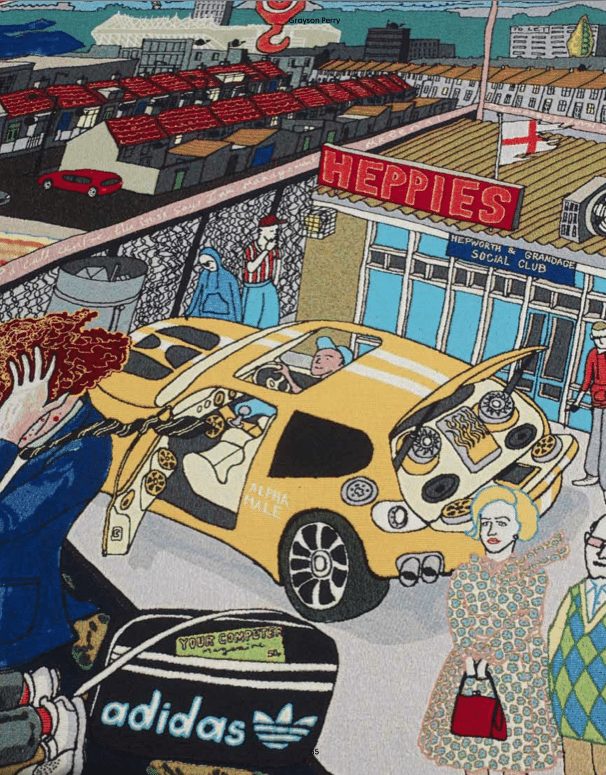

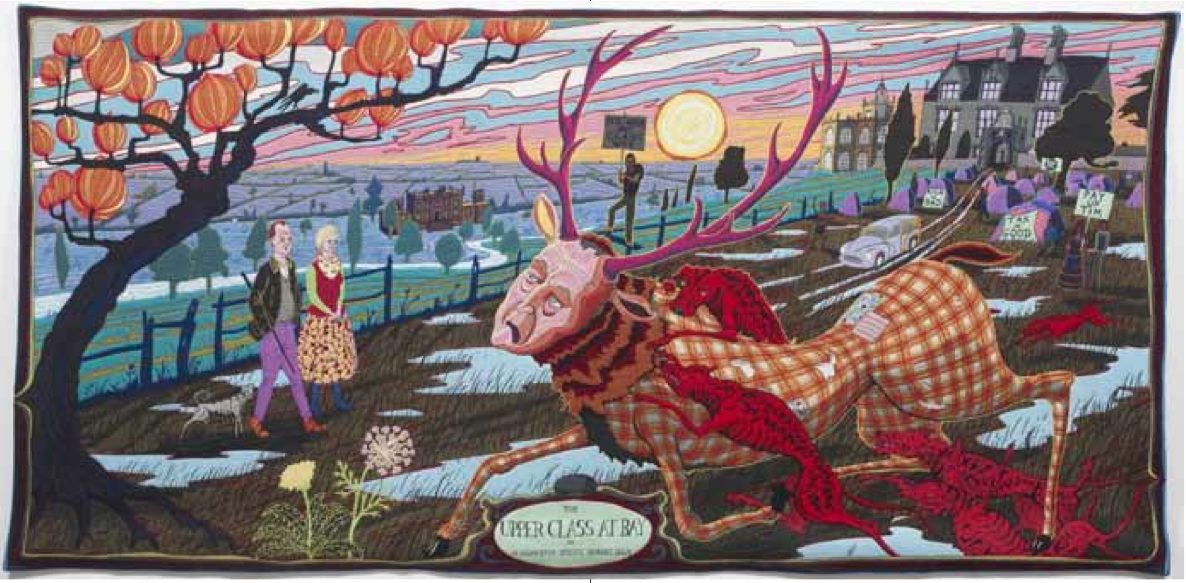

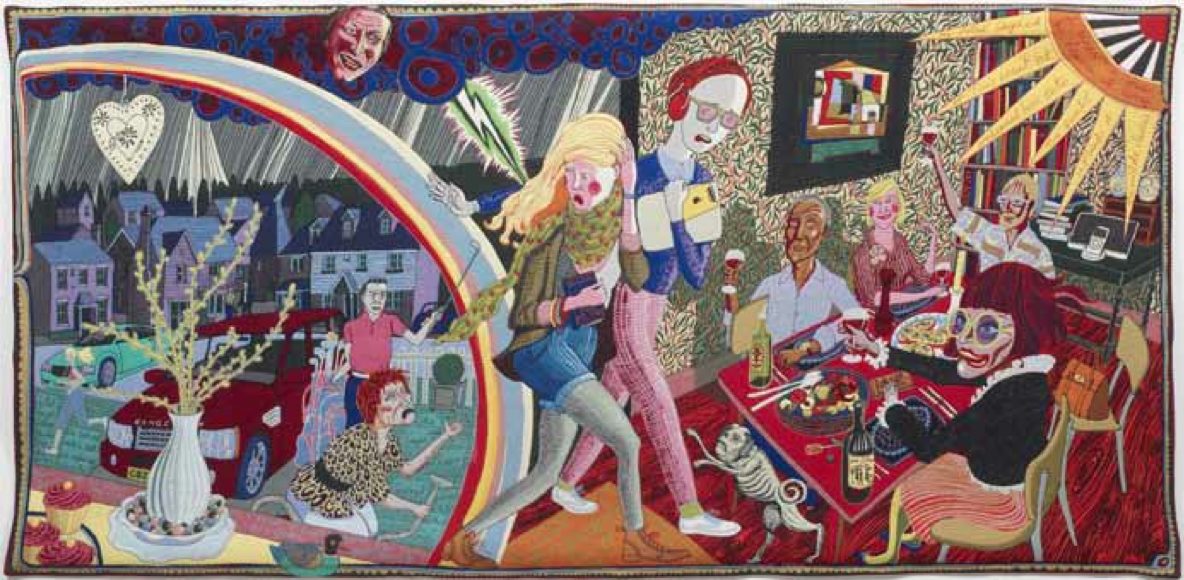

The six tapestries, entitled The Vanity of Small Differences. that were the result of his anthropological investigations into British class mobility and the aesthetic tastes of these finely calibrated groups take their inspiration from A Rake’s Progress by William Hogarth. In his eight paintings Hogarth tells the story of Tom Bakewell, a young man who inherits a fortune from his miserly father, only to spend it all on fashionable pursuits and gambling, ending his days in the debtors’ prison and the mad house. In the tapestries, shown at Victoria Miro, Perry has created his own modern-day morality tale, which also draws on imagery from some of the Renaissance paintings in the National Gallery that he loves such as Andrea Mantegna’s The Adoration of the Shepherds and Bellini’s The Agony in the Garden.

Had he ever thought of himself, during the filming of the series, as something of a latter-day Margaret Mead, the legendary and controversial American anthropologist, who studied the sexual mores of the Trobriand Islands? Couldn’t his investigations be criticized as a form of colonialism, with the people of Sunderland and Tunbridge Wells standing as the exotic ‘other’ in the eyes of a knowing London artist? “Well, I wasn’t an impartial observer”, he admits. “It was a balancing act. I didn’t want to come across as holier than thou. I think I’m quite an empathetic person. It wasn’t some sort of Chav porn. There was something bitter/sweet about the experience of the working men’s club.” But hadn’t he secretly been judging them? Didn’t he have his own idea of what ‘good taste’ should be? “Well, we all carry round ideas of what we think of as good taste”, he answers. “But there is really no such thing as bad taste if you back it up with confidence. There is a lot of middle class anxiety about taste. Confidence is the most expensive commodity. We live in a busy cultural landscape so it’s hard to find an original voice. Often taste can be a form of homogenization, of being seen to fit in with a group. A typical house can be a bit stark, a low-rent version of minimalism, we live in an IKEA-dominated world.”

And which of the three places had he enjoyed visiting the most? “I had most fun in Sunderland, though more interesting conversations in Tunbridge Wells, and the Cotswolds was the most beautiful, but none of them was really my tribe.” What tribe is that, then? I enquire. Bohemians, Hoxton Bohos? ‘Not really’, he says. “North London media slags. After all I do live in Islington.” Does he have a problem, then, with the fact that he has become so middle class? After all, his young life in Chelmsford and Bicknare Essex–with an absent father, a violent stepfather, a younger sister and two step brothers, when he had a penchant for making model planes–couldn’t have been more different. “You have to relax into it. I hate those chippy types from working class backgrounds who sit around eating couscous. You just have to get on with it and accept who you are.”

I wonder if he thinks he could apply his sociological scalpel to London. But London, he suggests, is very different. It isn’t homogeneous. It’s a multi-cultural city. Most people are immigrants, as are many of the city’s artists who’ve come from provisional art schools to seek their fortune among the streets they so often assume will be paved with gold. When he arrived in London in 1983 the art world was a very different place. In those days it was much more left wing. Artists such as Stuart Brisley and Helen Chadwick were stars and Marxism was the dominant ideology. He was attracted by street culture, by fashion and what was going on in the clubs, though he didn’t have a clear career path. He’d attended Portsmouth College of Art and lived a hand-to-mouth existence in squats, at one time sharing a house with the milliner Stephen Jones and Boy George, the three of them making an outrageous trio in their outlandish outfits at Blitz in Covent Garden.

Coming from a small backwater he only knew he wanted to be an artist and that he had absolutely no aspiration to be “Mayor of Hicksville”, but he didn’t have a clear trajectory. In these early days his principal interest was film. For a while he lived in a house full of filmmakers and made what he now admits were “rather pretentious” super 8 films. What interested him was “naffness”, in doing the thing that was least fashionable; in many ways, it still is. “I’m interested in the texture of contemporary life and in the ordinary and the average. But the art world now is a very different: more professional, more driven by money. Where did all those art PRs spring from?” But aren’t tapestries rather elite objects, I suggest, the sort of things that decorate great houses? “Yes, but I like the irony of a club singer from Sunderland being the central hero.”

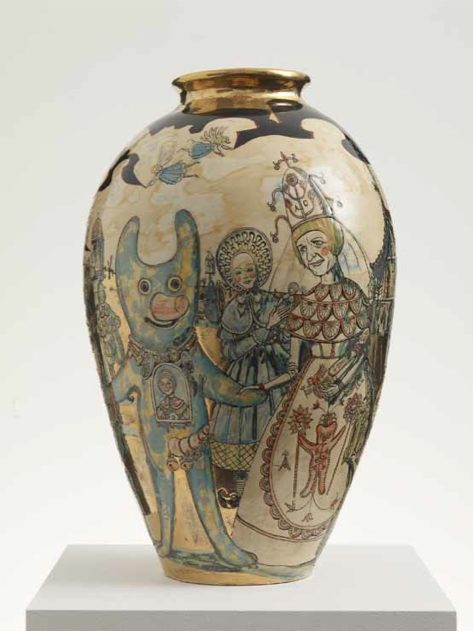

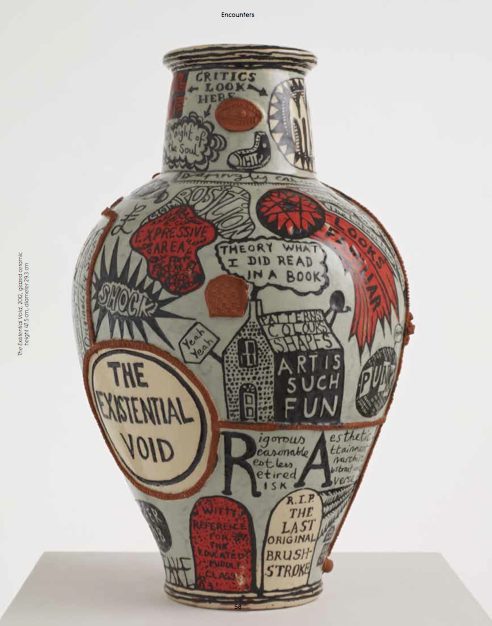

On arriving in London he didn’t do a postgraduate course and started to make pots at evening school. “I didn’t throw pots, I built them. I really had zero skills. I only made plates because I couldn’t do sides. I’m not a classically trained potter. I carve and mould on the surface of the wet clay. Slipware is a very traditional English form.” We sit upstairs in a quiet room at Victoria Miro, while below the gallery bustles with people looking at his tapestries (while we were on the stairs two very middle class, rather flustered ‘ladies’ came up and asked for his autograph), and he points out a rather wavy plate in the middle of the long designer table. “That’s one of my early ones.” Does he still find it difficult to make pots? “No, I’m rather good at them now. I don’t pretend that I can’t do them. I’ve always made them as well as I can at the time, though opening the kiln is always a bit of a controlled act of disappointment. But I’ve never wanted the craft element to dominate, to be the subject. I never wanted it to be the headline. After all there are plenty of hideous objects that are beautifully made. I’m a postmodern potter, astringent, not a purist. I’m not Bernard Leach.”

Was there a conflict, I wonder, in using a medium that many considered to be a craft? After all craft has always had a complex, and supposedly inferior, relationship with fine art. “It’s not really a question of art or craft. Nowadays anyone can have a cottage industry at home with a computer. Everyone has one in a back room, along with a printer and a photocopier. You don’t need factories. As an artist you can pick through the 21st century and use what you find to your own ends. There are no longer a series of “isms” in the art world. You can do anything you want if you can do it well. In traditional crafts the maker remains at arm’s length from the object and the person is less visible. That’s what my exhibition ‘The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman’ at the British Museum addressed. But if something has got Picasso’s name on it then it’s worth something. As an artist you have to edit. You live or die by your reputation. Nowadays I can literally “draw” money.”

He was, he tells me, deeply affected by the Hayward Exhibition in 1997 of outsider art, Beyond Reason: Art and Psychosis, which included works from the Prinzhorn Collection. Prinzhorn, a doctor in a Heidelberg psychiatric hospital, had collated thousands of works by artists from psychiatric institutions, fascinated by the quality that was produced by those outside the mainstream. He has, Perry continues, always had a fear of being part of the establishment, though that is what tends to happen to successful artists, they get sucked in to the whole art arena. “But you just have to deal with it. It’s all grist to the mill.” When I suggest that anonymity is a good place for an artist to inhabit and from which to make work, he agrees. But now, he says, he’s not only recognized in trendy galleries, but since the TV series, in the streets and the pub as well.

Does he think that he could make a programme investigating another nationality in the way he has done with the English? “No I don’t think so. I feel qualified to comment on Englishness. I am embedded in and representative of the culture. I couldn’t make work about somewhere that I didn’t know intimately. I have to have an emotional stake and understand the references.” What about those 18th-century artists who did the Grand Tour looking for inspiration by going to Venice, Greece or the exotic East? I ask. “Yes, but those history paintings were like stage sets. They gave artists the chance to show off. What matters to me is truth seeking and what feels right at the time.”

I ask, given the fact that his wife is a psychotherapist, if he agrees with the theory put forward by the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein that art is a form of reparation for childhood trauma. After all, he had a fairly troubled childhood. He agrees that art can be a salve and that it can grow from psychic wounds. “What I do is borderline art therapy. I’ve done a great deal of therapy in the past and am pretty self-aware now, much more alert to dysfunction coming down the line. Nothing is hidden any more. Therapy is like tidying up your tool shed. You clean and polish what works and keep it, then abandon what doesn’t.”

I mention that the German poet Rilke refused to be psychoanalyzed by Freud when they met, fearing that if he lost his neurosis he would also lose his genius. “I’ve heard that argument before”, he says, though it’s not one with which he particular empathizes. “Certain personality traits are fixed in early life and become very deep rooted; they are preverbal and therefore very hard to change. Something that happens to us at the age of two affects the trunk of the tree not just the tips of the branches.” And being a transvestite? Does he have a different experience of that now? “Well, we are a much more tolerant society than we were, so being a transvestite is easier. But when I was younger and joined a transvestite society you had to be anonymous. That is why I was Clare. But really Clare is just me in a dress. It just means that I have this feminine persona I can dip into. I never put my make-up on twice the same way.”

And what about his working practice, does he make pots every day? “I am mostly in the studio drawing. But I like to sit down in front of the telly with a couple of beers and draw when I’m pissed. It’s important to be relaxed. It took me three or four goes to design the first tapestry. It’s actually quite quick to make a pot so I like working in different media, though I rather enjoy the boring bits of pot making.”

And if he had to sum up his mission statement as an artist what would that be? He goes quiet for a moment and looks out of the huge plate glass window on to the pond outside. “That’s a hard one. People don’t usually ask you questions like that. David Hockney’s “colours and shapes” isn’t a bad summation. My ideal goal is to make something beautiful.” But isn’t beauty a largely historic and social construct? I ask. ‘Well it’s ringed with many defensive walls. Beauty is a massively complex construction. But I believe in beauty. I want to make works that fascinate and delight. I have become part of the lobbying group who can decide what beauty is and what is seen as beautiful.” So what does he see as beauty? “Oh the Golden Section, harmony and colour, significant form, though, of course, it is mediated by social context. It’s a collection of qualities that you can follow through. Maybe they won’t last but something that is particular probably will. An object that is of its time has an emotional charge.” Like flying ducks on the wall? “Yes, people are happy to talk about what they hate rather than what they like because that is too emotionally exposing.”

It’s a mark of having made it that time becomes precious. Suddenly, while we are talking, I become aware that Grayson is looking at his watch. He has to go. He has a meeting. The following day he is doing an interview on Radio 4 and then there is the visit with Victoria Miro and her husband to Chris Ofili’s ballet at the Royal Opera House when he’ll probably turn up resplendent in drag. F. Scott Fitzgerald once said “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me”, but so, too, are the famous. New vistas are opened, doors unlocked. Perry may have started his career in an evening class making wonky pottery plates because he wasn’t very good at sides, but now he is constantly on the radio as a celebrity guest, there is talk of a new TV series and he hopes that one of the sets of the tapestries will be bought by a public collection. Not bad for a shy little boy from Essex who made model aeroplanes and liked to wear dresses in secret.