It seems that female representation has never been more topical, in the art world and beyond. Just this year, the Tate Britain unveiled an all-female rehang of their collection to celebrate sixty years of women’s work, while last November the National Gallery acquired a self-portrait by seventeenth-century painter Artemisia Gentileschi—only the twentieth work by a woman to enter a collection of more than 2,300 European paintings.

Gentileschi is just one of the more than 400 artists who feature in Great Woman Artists, an encyclopaedic tome (published this autumn by Phaidon) that spans 500 years of art history. The oldest, Properzia de’ Rossi, was born in 1490 in Bologna; while the youngest, New Yorker Tschabalala Self, is still in her twenties. As is to be expected from a book with such an ambitious scope, this is a heavyweight title (and the large-scale hardback weighs about enough to knock out any naysayer). Without a doubt, this is a book to be reckoned with.

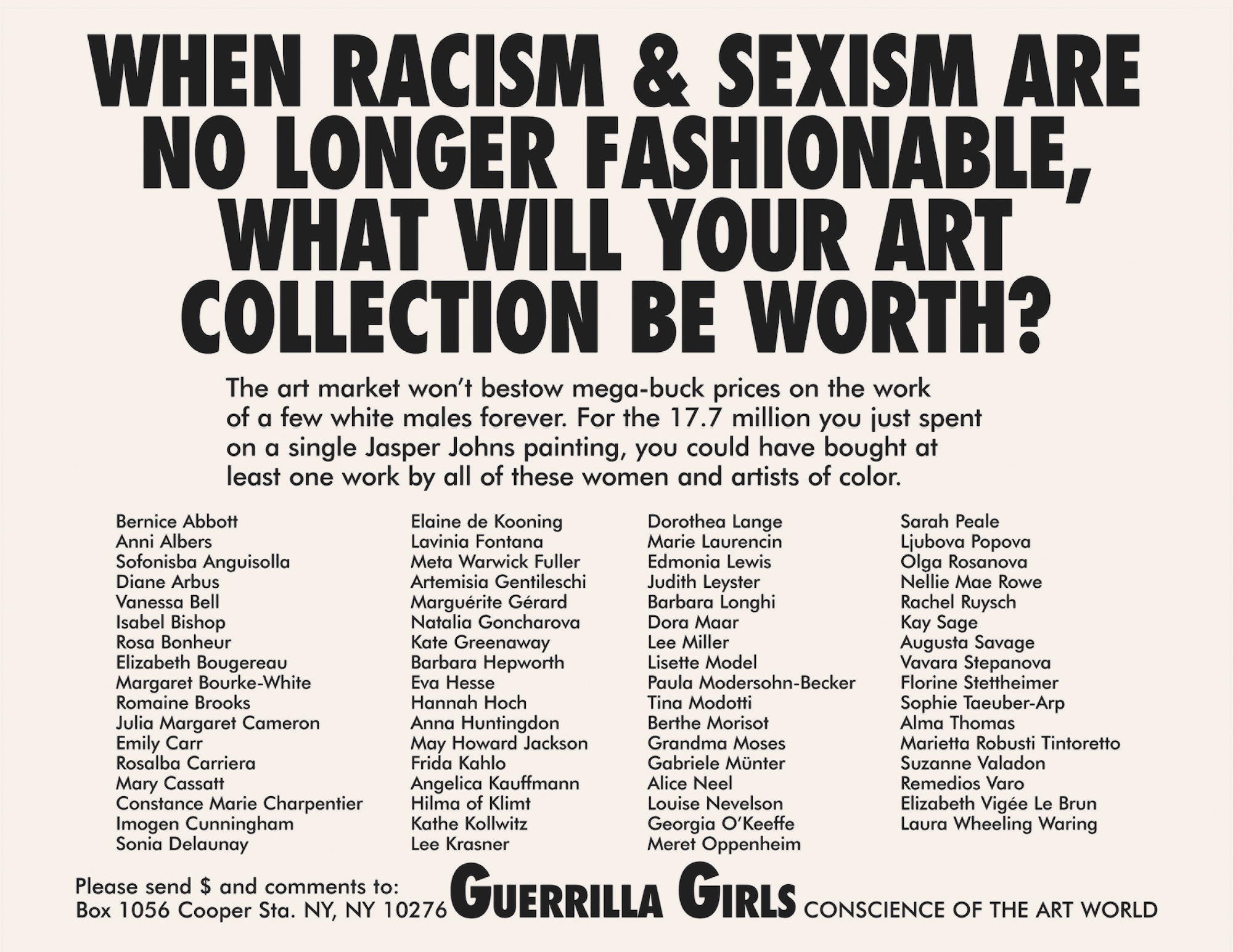

Guerrilla Girls, When Racism & Sexism Are No Longer Fashionable, What Will Your Art Collection Be Worth? 1989 © Guerrilla Girls. Courtesy guerrillagirls.com

With the titular nod to Linda Nochlin’s seminal 1971 text, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, editor Rebecca Morrill makes clear her aim to set the record straight. As Nochlin famously wrote, “The arts, as in a hundred other areas, are stultifying, oppressive, and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class and, above all, male. The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education.”

In her introduction to the book, Morrill makes short work of Gombrich’s Story of Art; published in 1950, it featured no female artists. It is a staggering omission, and one that adds fuel to the righteous anger that lights up Great Women Artists. This is not a mere coffee table book, but a fierce riposte to the historical injustices that remain entrenched in the structures that continue to privilege men today. Even in 2019, male artists continue to achieve higher prices in the art market. The top price paid at auction for a painting by a living male artist is $80m (David Hockney), as compared with $12.4m for a living female artist (Jenny Saville). They are also more likely to have representation by a commercial gallery.

“This is a fierce riposte to the historical injustices that remain entrenched in the structures that continue to privilege men today”

Included are household names that many will recognise in these pages, from Georgia O’Keeffe to Cindy Sherman, Judy Chiacago to Barbara Kruger, but equal space has been given to those who are less well known, such as Nina Chanel Abney, Zanele Muholi and Juliana Huxtable. Every artist included in the book, no matter how great their reputation, has been given an even playing field. It is reflective of the decidedly egalitarian approach that defines the book, with artists ordered alphabetically rather than by age or stature.

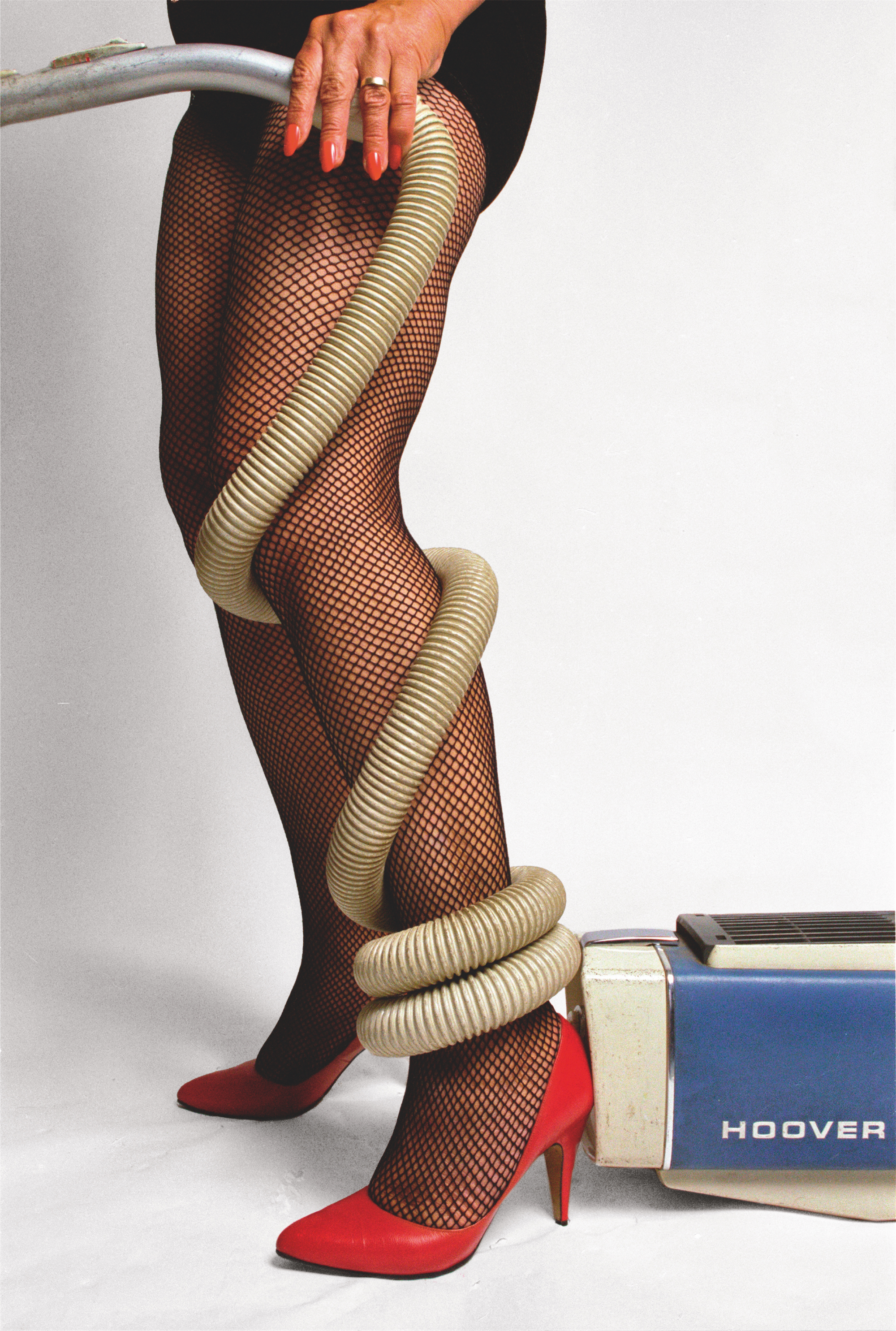

It is an indexing choice that enables radically different artists to rub up against each other. Chinese painter Pan Yuliang, best known for her portraits and nude studies of Chinese women, sits opposite radical performance artist Gina Pane, who often inflicted injuries on her own body. Birgit Jurgenssen, an artist who used drawing, photography and performance to critique the social forces that confine women, can be found opposite Frida Kahlo, another artist who used her work to confront the restrictions that she experienced as a woman. There are surprising connections to be forged here, moving between distinct periods, styles and creative approaches.

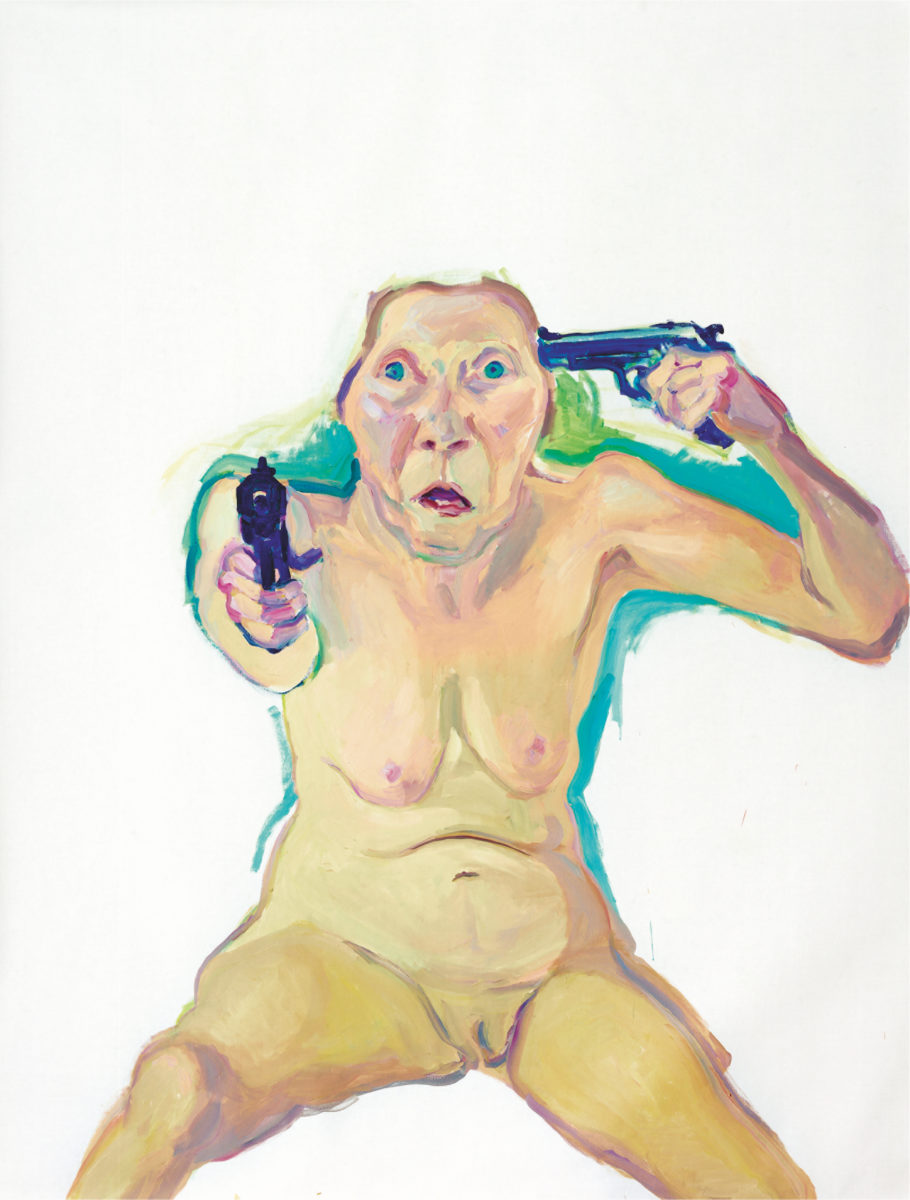

- Maria Lassnig, Du Oder Ich (You Or Me), 2005 © Maria Lassnig Foundation, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo by Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

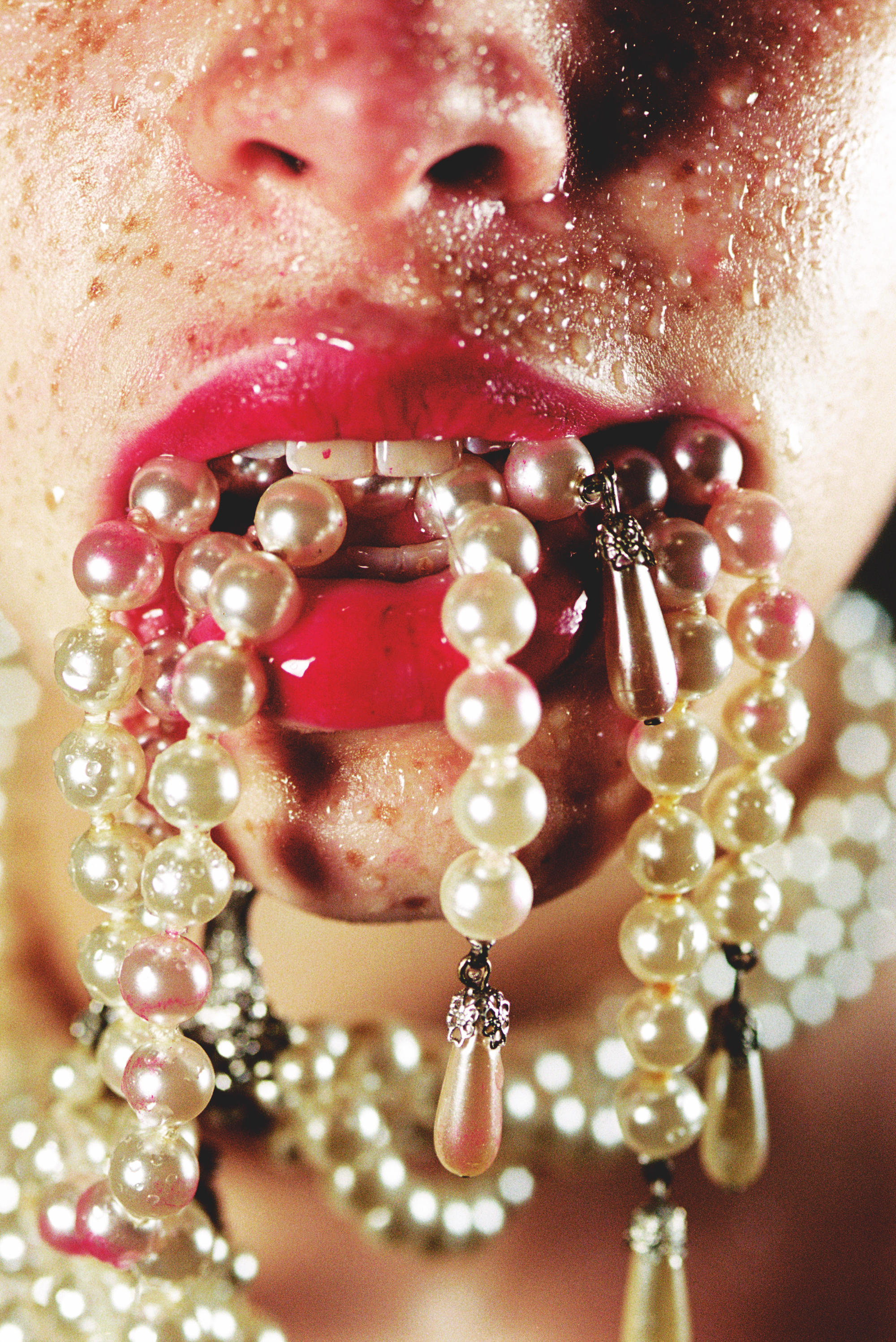

- Juliana Huxtable, Untitled (Psychosocial Stuntin’) from the series ‘Universal Crop Tops’, 2015 © and courtesy the artist and JTT, New York

As Morrill puts it, “Notions of greatness could shift over time and space, rather than remaining fixed.” This fluidity is made clear by the variety of voices in Great Women Artists, which span race, class and sexuality. Similarly, the question of gender itself is drawn into question, with Morrill’s suggestion: “In the twenty-first century, it might seem irrelevant to talk about artists in terms of gender at all.” Transgender artists are also included, as well as those who confront or overturn their own female or feminine identity.

In the digital age, the role of social media—and particularly Instagram—cannot be overlooked when it comes to female representation. Katy Hessel’s The Great Women Artists, an influential Instagram account which also nods to Nochlin’s proclamation in its title, spotlights female artists and draws attention to the work of many, past and present, whose work continues to be overlooked.

However, while Morrill acknowledges the value of such accounts, she points out that the lax copyright laws for the reproduction of images on social media may not last forever. Instagram, and particularly art history-related Instagram accounts, rely on the ready availability of free images to share and celebrate the work of the women who, in many cases, have never received fair payment for their labour in the first place. If copyright laws are tightened in future to address this, it will present a challenge to the sustainability of these online platforms.

“There are surprising connections to be forged here, moving between distinct periods, styles and creative approaches”

Great Women Artists sets out not just to tell a different story for the women who have been left in the shadows, but to fill the void that has led to so many female artists to disappear into the darkness. As the most extensive anthology of women artists to date, it lights the way for the change to come. Museums are just beginning to address the gender imbalance of their collections, while galleries are mounting more shows than ever before of female artists.

As Morrill wryly concludes, this is a book that she hopes will grow outmoded as the years go by, when the names in it are just as well known as many of their male counterparts, “and until there is no need to ask whether an artwork is made by a male or a female.”