Walking around our own cities or hometowns, it is all too easy to slip into a kind of lazy indifference. With headphones on, in a music-infused daydream, I can pretty much walk to work and see nothing at all. Lupita, I’ve Kept You An Apricot On The Tree by Guadalupe Ruiz is a challenge to this indifference. Designed as a small children’s book dedicated to Ruiz’s son Octavio, it takes readers on a dérive-style walk around Ruiz’s childhood hometown of Bogotá, a place Octavio has never been.

Ruiz moved to Switzerland in 1996 at the age of seventeen with the intention of studying art and, though she has stayed for twenty-two years, she takes frequent trips back to photograph the spaces and people she grew up around. “It was important for me to find the perspective to see clearly the city where I spent my childhood and adolescence,” she explains in an exchange over email.

Often Ruiz’s previous projects, such as Nada Es Eterno, have placed her large family centre stage, in candid but strikingly cinematic photographs. In short films, she extends these encounters with family life into absurdity, as the same family members act out and perform for the camera. “They have always been unconditional with me,” Ruiz responds when I ask how they react to being her subjects. “It’s a family affair, in Colombia your family supports you no matter what.”

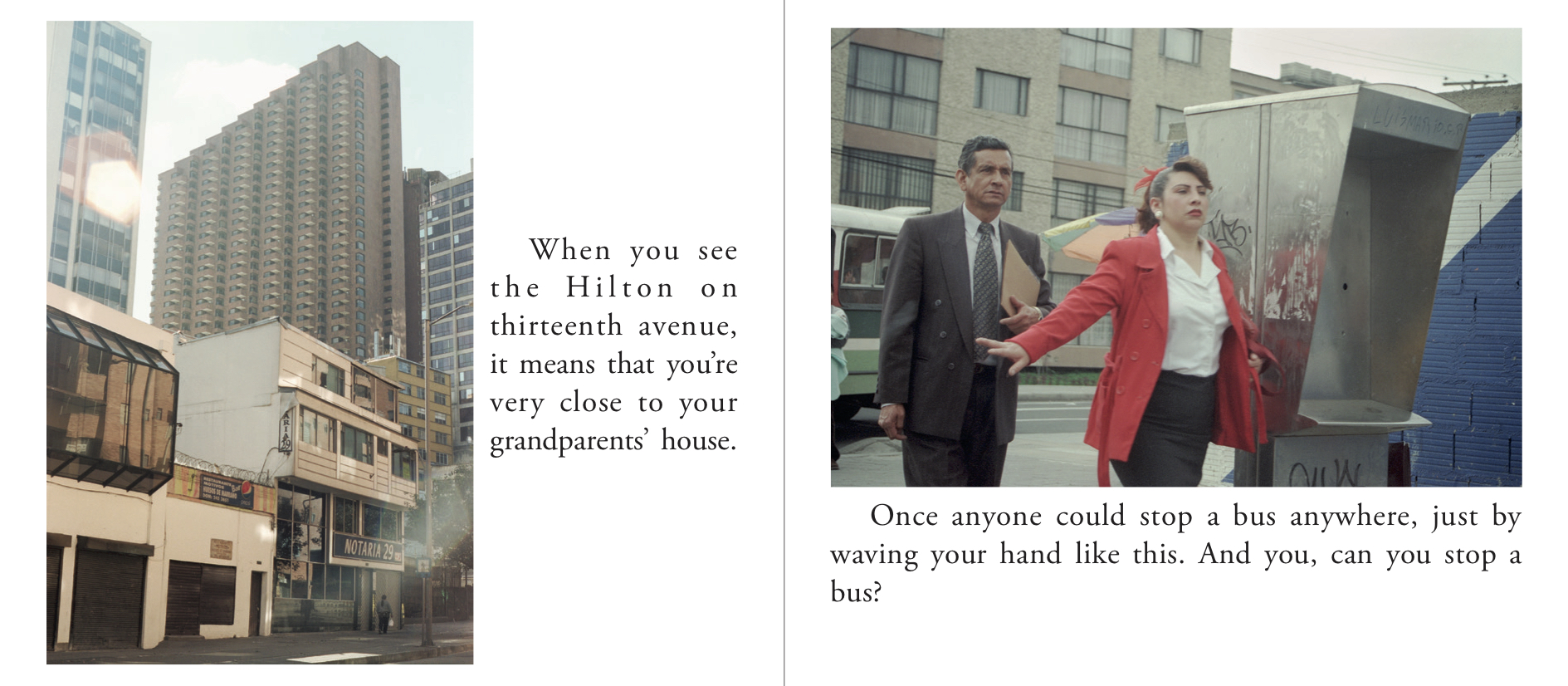

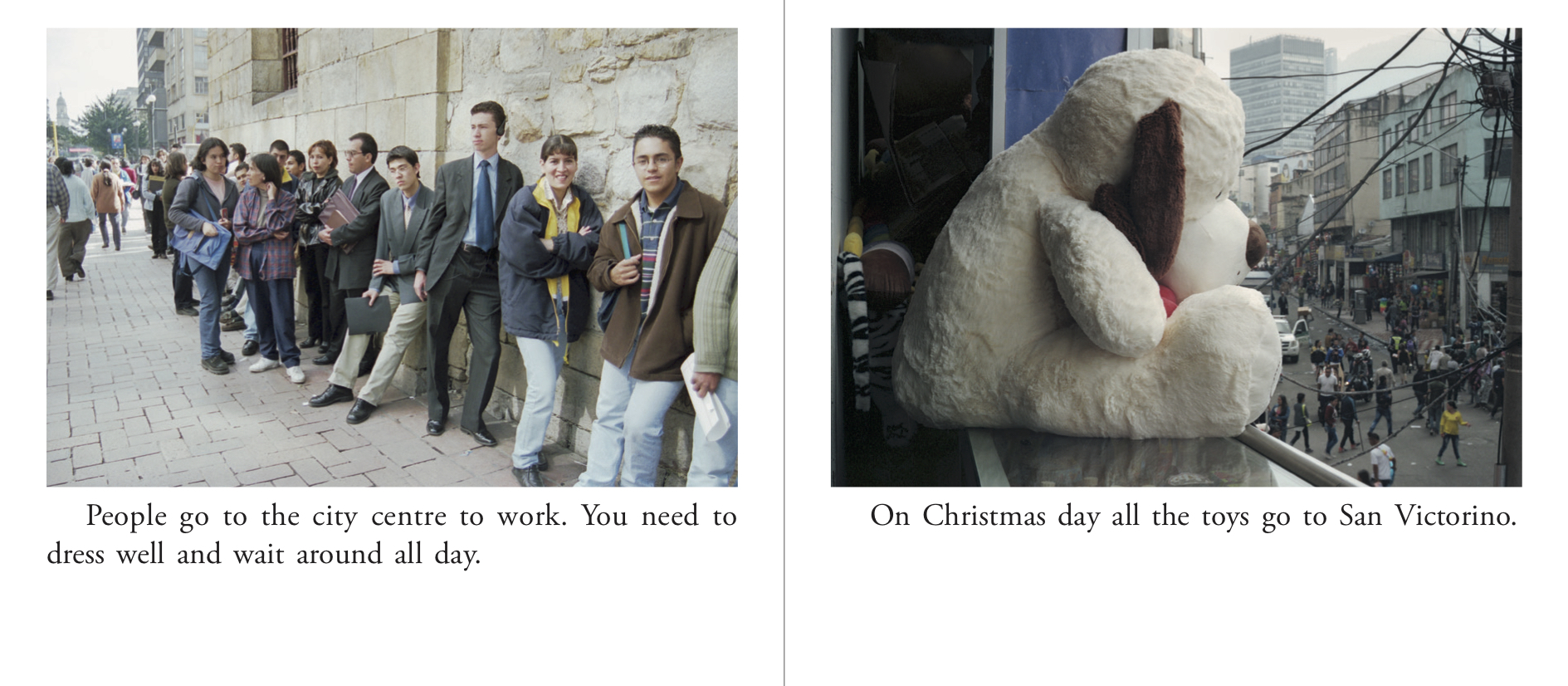

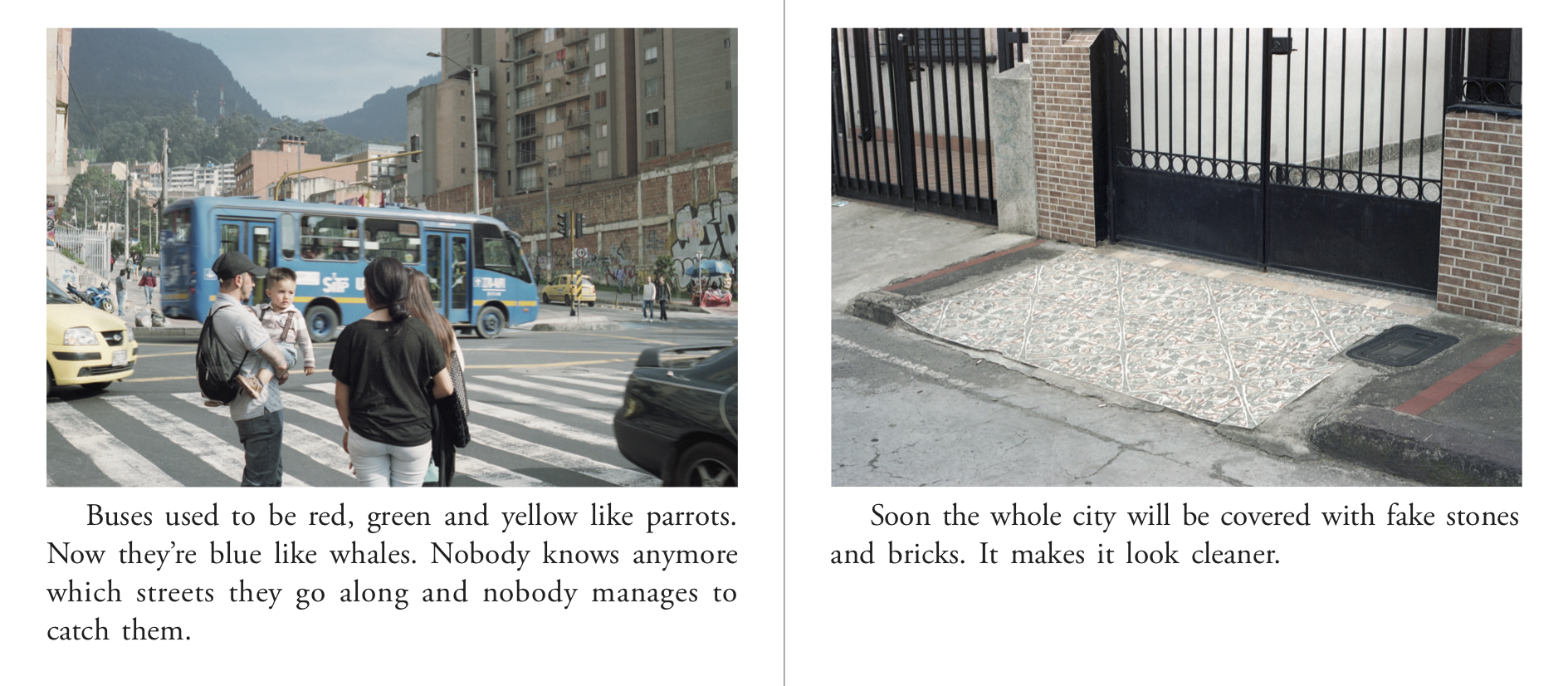

Yet the city of Bogotá—bustling with busy people, built up with glassy office blocks—is the fickle and chaotic main character of Lupita, I’ve Kept You An Apricot On The Tree. Using images from her own archive that capture the city in the 1990s, 2000s and 2017, the book depicts an array of everyday city scenes: trolley-packed supermarkets and people waving down buses and quiet residential streets. “Normally I remember what caught my attention when I took a picture but in this case I found them in my archives, and I realize I’ve no idea why I took some,” explains Ruiz, about the images that function as the starting point for the book’s whimsical narration by writer Noëlle Revaz. “Because she is a mother too it was easier to write something addressing a child…I brought my sequence of pictures [to Revaz] and chose some key words for each image.”

“The narration takes our hand and points to the big buildings and busy people”

A photo of a giant novelty waffle triggers a daydream in which a woman takes a bite out of her child’s head, with the text deadpanning, “I made a mistake! That’s not a waffle, that’s my little boy!” Revaz’s narration takes our hand and points to the big buildings and busy people; cars themselves become protagonists, the whole world through a child’s eyes is personified. The innocent language and surreal humour, however, belies the difficult and “adult” social issues that are present in any city: homelessness, police surveillance, social class—opening them up to a child or, indeed, anyone who is new to Bogotá.

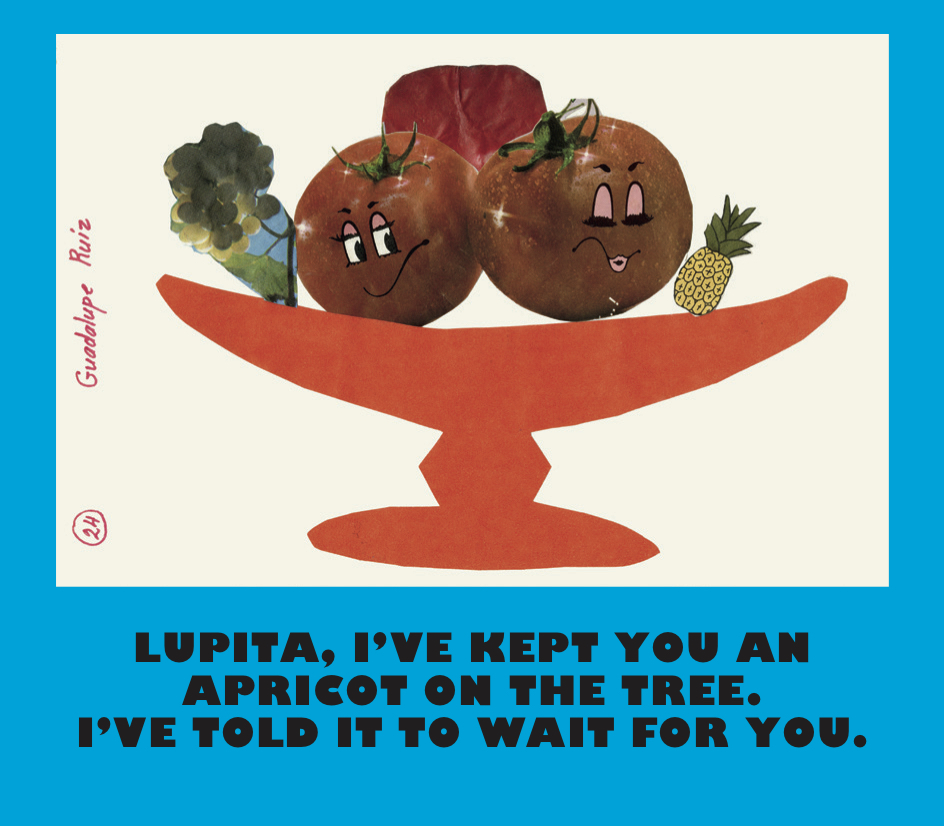

The book’s surreal title is itself a line from Ruiz’s grandmother. “I chose this line because my grandmother only once in my life sent me a postcard, and she wrote this strong sentence which meant a lot to me”, the artist recalls. “Firstly, the fact of living in another country since the age of seventeen, the patience (something that I miss all the time) and the unconditional love given by your family. My grandmother was somebody with an unusual life, she raised fifteen children. I don’t know how but she did it…Because this book is a kind of declaration of love it was important to use something that remains mine.”

“The wandering story of Lupita I’ve Kept You An Apricot On The Tree serves as a tender and playful bridging of gaps”

Thus the wandering story of Lupita, I’ve Kept You An Apricot On The Tree serves as a tender and playful bridging of gaps: the gap between a mother and a son, between generations of family members, that between the past and the present, the geographical gap between Colombia and Switzerland, the gap between adolescent understanding and adult hindsight, and the gap between personal and external perceptions of the city of Bogotá.

It is no secret that Colombia in Western media is so often characterized abroad as a very troubled country. I do a cursory Google search on the country, and it immediately brings up a British newspaper article titled “Colombia and Corruption”. I ask Ruiz if she ever seeks to confront these perceptions in her work or if, in fact, she pays attention to them at all. “Of course the cliché of Colombia will be always the same,” she explains. “It’s a pity because things are more complicated than they look and the Europeans and the Americans think that they have the truth about any subject. Sometimes they only look at the surface issues.”