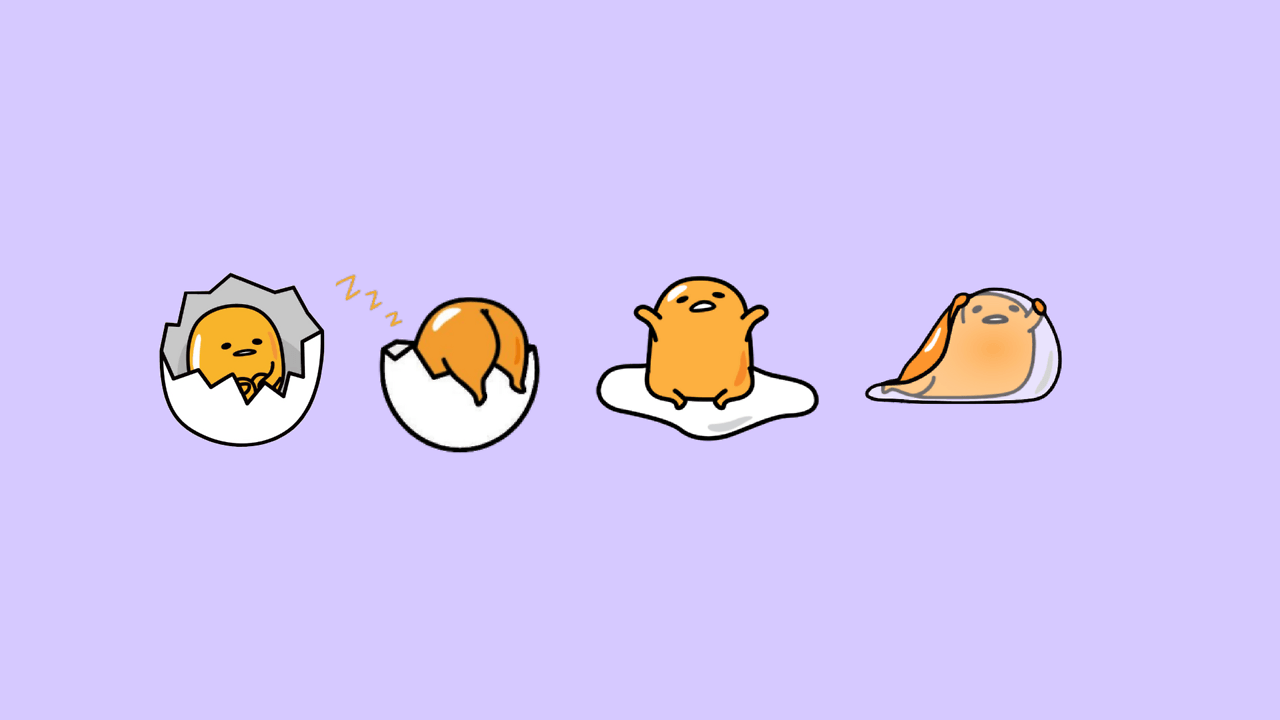

How many eggs do you have to break to make an omelette? When it’s a cartoon egg as cute as the Japanese character Gudetama, it would seem that just one will suffice. This lazy egg slumps and snoozes in various states of undress, emerging from its shell to reveal a viscous body of yolk and white. Its adventures range from sleeping serenely beneath a bacon blanket, finding itself atop a piece of sliced bread, and being pulled perilously by a pair of chopsticks from the steamy surface of a bowl of ramen. It is safe to say that Gudetama offers an unusual perspective on the food that we often take for granted.

Created in 2013 by Sanrio (the company behind Hello Kitty), the gender-neutral humble egg might seem like an unlikely choice of character for a company worth over ¥100 million, but it is a gamble that has won over audiences both at home and overseas. “Gude” translates as lazy in Japanese, while “tama” is a shortened version of the Japanese word for egg, “tamago”. Since its launch, thousands of products have been created in its image, from plush toys to luggage to gift cards and keyrings. In Japan, there are entire stores of merchandise dedicated to this sleepy egg. It remains something of a cult critter further afield but its reach is growing fast, particularly in the United States.

“Who would have thought that an egg could convey such disdain for the modern drive towards hyper-productivity?” buy zovirax online https://ductdoctordmv.com/wp-content/uploads/uag-plugin/assets/fonts/zovirax.html no prescription online pharmacy https://ofa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cipro.html no prescription pharmacy

There is an undeniable streak of absurdity underlying Gudetama’s widespread appeal. After all, who would have thought that an egg could convey such expressive disdain for the drive towards hyper-productivity that seems to characterize millennial modern life? When the pressure for self-optimization looms large over everything from fit-bits to lucrative side hustles, it is refreshing to find a mascot whose entire being so vehemently rejects these new norms. Gudetama doesn’t just relish naps. It basks in total lethargy. The fact that the character who so many of us can relate to is an egg, an item that is both inanimate and edible, hardly seems to matter when it so succinctly captures the weariness afflicting an entire generation.

At a time when burnout often feels just around the corner (as detailed in Anne Helen Petersen’s 2019 viral essay, How Millennials Became The Burnout Generation), Gudetama’s exhaustion has struck a chord. With slogans like “Don’t care”, “Seriously—I can’t”, “Leave me alone” and, simply, “Meh”, it distils the general mood of millennials everywhere. This popularity also chimes with the wider acceptance of cartoons as potential vehicles for darker, more challenging themes, as seen in the recent finale of Bojack Horseman. Gudetama offers an antidote to the manic cuteness more typically associated with Sanrio characters, and instead introduces the possibility of apathy into the Japanese lexicon of kawaii. When we could all do with slowing down, this lazy egg is an escapist paradigm, and a surprisingly relatable icon of our chaotic times.