“Money, it turned out, was exactly like sex. You thought of nothing else if you didn’t have it and thought of other things if you did.”

—James Baldwin

As a child I made an observation to my mother about a couple who seemed strange, both as individuals and as compatible beings. I said I didn’t understand why they considered either to be desirable. Of course, I knew nothing about sex. She said: “God makes them, and He matches them.”

I have discovered in the decades since that if there are some practices that I personally know nothing about, such as sadomasochism and pederasty, then I know nothing about them. Sexologist Alfred Kinsey claimed: “The only unnatural sex act is that which you cannot perform.” He ought to know because he saw everything.

To claim that Americans are uptight about sex is an understatement. Their attitudes are derived at an early age from those who decide what they should see or think. Anthropologists know that sexual practices among human societies vary greatly. People in one culture, when told the sexual behaviours of another, often find them to be disgusting.

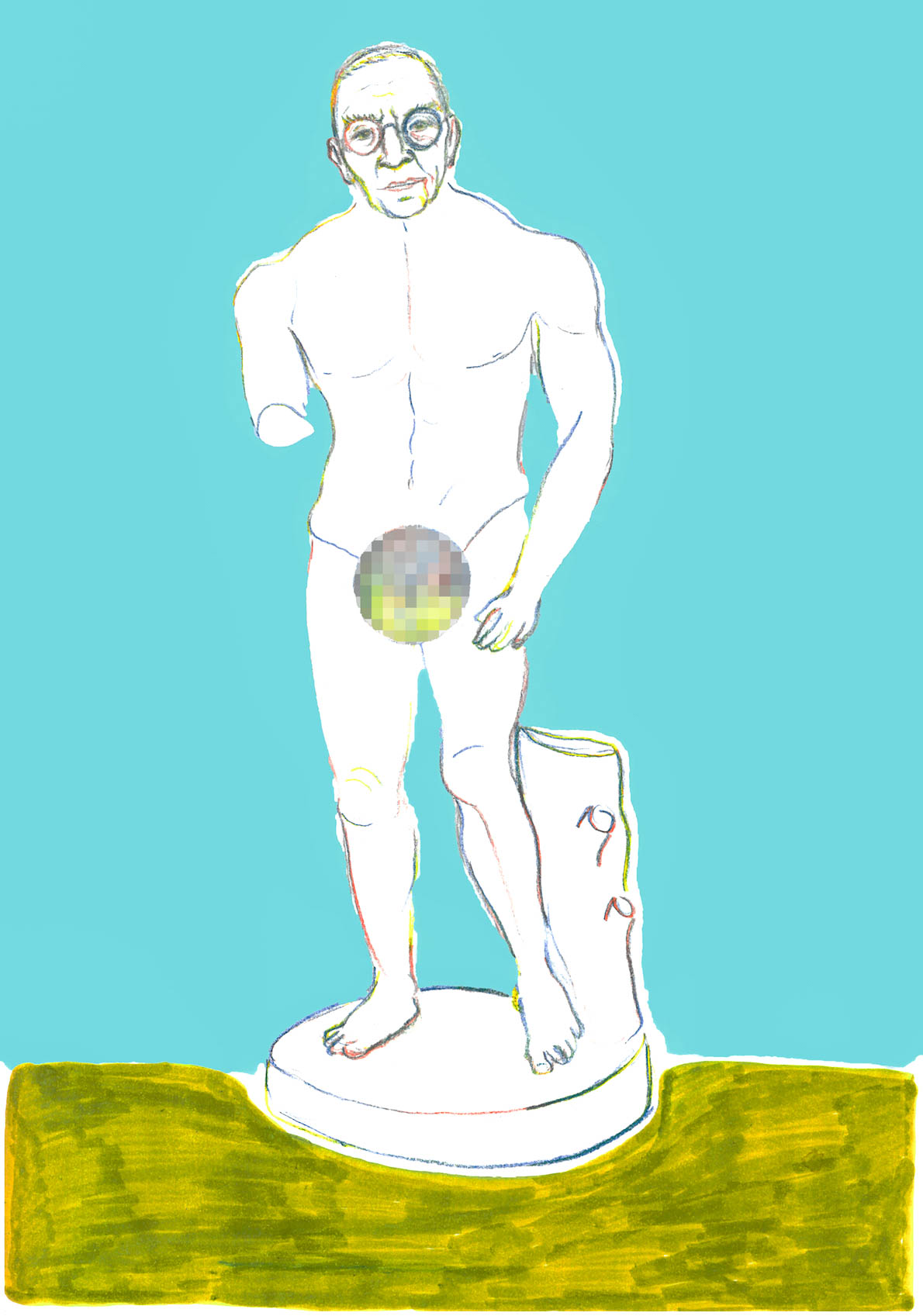

In a recent US TV programme about Italy, the sex organs of classical Roman and Greek statues were fuzzed out (if they hadn’t already been chopped off by religious zealots). The action is one of hundreds of examples of America’s hypocritical censorship.

People will commonly say: “We dated for two years” instead of: “We had sex for two years.” Everyone accepts the comment as code. Is the “f” word wrong? American society says it is. Language will tell you everything; it is a window into thoughts, principles and opinions. Thus, certain language, especially about sexual acts, is taboo, even in the bedroom.

Another sexual taboo is infidelity, a particularly modern predilection. Historically, royals mostly had sex with their chosen spouses for procreation to fill future dynasties; otherwise, their pants and knickers were more down than up with other people.

The percentage of people who say they believe that infidelity should be illegal must necessarily include those who cheat, based on the figures in numerous surveys. Does this make sense? It does if you believe that the majority are talking out of both sides of their mouths.

Politicians and religious figures often purport to living by the strictest moral codes, occasionally finding their true behaviour exposed by a loudmouth press. It’s called hypocrisy or, according to the dictionary: “the claim or pretence of having beliefs, standards, qualities, behaviours, virtues, motivations, etc., which one does not actually have.”

How do artists figure in all of this? They aren’t all hedonists, but it’s easy to think that they are when you take a look at the works of Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe and others.

The brouhaha provoked by the Mapplethorpe travelling exhibition from 1988 to 1990 has faded. In an article in The New York Times at the time, Barbara Gamarekian reported: “The Corcoran Gallery of Art has canceled a planned retrospective of the work of the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, anticipating that its content would trigger a political storm on Capitol Hill.”

I met Mapplethorpe once. He lived and worked in a loft on Bond Street in New York City, one street away from mine on Great Jones. His public persona was mild mannered but so was that of Ted Bundy, Ted Kaczynski and John Wayne Gacy, the serial killers. Mapplethorpe’s subject matter is schizophrenic—from images of flowers and clothed men and woman to masochistic and nude kinky poses. Viewing the photos years after they were taken, I recalled having seen a number of the men in 1970s discothèques.

When I was about eight years old, I visited a friend who lived in a house that was several down from mine. In a bedroom for his aunt and her husband, there were pornographic pamphlets under the mattress. They showed comic-strip characters having sex. The characters that appeared in every Sunday newspaper—Jiggs and Maggie, Joe Palooka, Popeye and Blondie—had exaggerated penises and large breasts. I brought one home and then forgot about it. When my mother found it she was very upset, interrogated me like a police sergeant for information about where I got it, called my friend’s mother to scold her, and forbade my visiting that house again.

Fortunately or unfortunately, pornography has since been redefined. According to French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, who was active in the 1960s, Mapplethorpe’s legendary Man in Polyester Suit with an exposed penis illustrates: “When everything is sexy, nothing is sex. It loses its definity, dissolves in the codes of power and beauty, disappears, and comes the epoch of a transsexual, an androgyn.” The 1980 photo that Artnet called “racy” sold for $478,000 in 2015 at Sotheby’s. When the cognoscenti say that pornography is OK, it isn’t pornography anymore.

When I was a young adult, I was obsessed with having sex, not knowing that I had little choice. The force of nature dragged me into uncompromising situations—with strangers, with people I knew, on dining-room tables, in airplane toilets, on stairs, in alleys, in the back of trucks. If the absence of fortitude sounds like an excuse, it probably was.

I have never understood why most children, even old ones, are repulsed at hearing the details of their parents’ sexual activities. Doesn’t everyone know that most but not all humans have sex? The proof is here: sex produced the readers of this column and the one who wrote it. Although, if sex were not taboo, people would probably be having less of it.

Perhaps the reason we find sex so complicated is its inevitable connection with other parts of life. As Shirley MacLaine noted: “Sex is hardly ever just about sex.”

Illustration by Rosalind Duguid