The Indigenous activist and community leader’s contribution to the 2024 Venice Biennale reclaims Brazil’s history from Western control to amplify the ongoing battle of its native people. Developed in collaboration with artists Olinda Tupinambá and Ziel Karapotó—also showing works in the pavilion—and the wider Tupinambá Community of Serra do Padeiro and Olivença, in Bahia, Ka’a Pûera: we are walking birds unveils the reality of Indigenous Brazilians in a celebration of their centuries-old customs and mysticism and revitalising vision of the future.

Below, Glicéria Tupinambá discusses the relevance of the project joined by co-curators Arissana Pataxó, Denilson Baniwa and Gustavo Caboco.

GB: How does “Ka’a Pûera: we are walking birds”, the title of this exhibition, feed into the overarching theme of the 60th Venice Biennale, “Foreigners Everywhere”?

Arissana Pataxó, Denilson Baniwa and Gustavo Caboco: The title of this Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere, is very precious to Indigenous communities; this notion of being a foreigner everywhere is not just a metaphor to us. Throughout the world, we were displaced from our lands, colonised and enslaved. Even today, we still strive to reclaim these territories, to be recognised by national states, to assert our existence. Ka’a Pûera (or “capoeira”) alludes to two interconnected interpretations: firstly, it refers to areas of cropland which—after being harvested—become dormant, giving way for low-lying vegetation to emerge and revealing the potential for resurgence. In addition, the capoeira is also known by the Tupinambá as a small bird that lives in dense forests, camouflaging itself in the environment. We see that Indigenous peoples in Brazil—and beyond—are like Ka’a Pûera, ressurging and camouflaging to resist and exist throughout time.

GB: To emphasise the existence and resistance of its Indigenous people, the Brazilian pavilion has been renamed the “Hãhãwpuá” pavilion. Why was this shift of narrative needed?

AP, DB, GCW: Hãhãwpuá is a word from the Pataxó people, [a native community nestled in the Northeast Brazilian state of Bahia]. In Brazil we have many names Indigenous populations relied on to refer to the territory before colonisation, many of which are still used today. This is not something that is in history books. There are over 300 Indigenous different nations in the country, each one with a different understanding of it, which is reflected in the language. Brazil can be defined in many different ways, Hãhãwpuá being one of them. We have chosen this specific name because of the artists that we are working with, but also because of one of the curators involved in the project – Arissana Pataxó, who is from the Pataxó people. The history of colonisation, too, at least by the books, starts by the very Brazilian coast they come from. To introduce Indigenous vocabulary into the art world has been a consistent effort for us in Brazil: we have made sure that the curatorial texts of spaces featuring Indigenous people contain Indigenous terms and words that can explain a way of thinking or an artistic practice. Before getting caught by the vibrancy of the Carnival or that of Brazilian vast diversity, it is important for people to understand the fight of Indigenous and Black communities to keep existing. This is a territory of resistance through art, where the old and the new merge to survive time.

GB: Glicéria, congratulations on such a powerful Venice debut! What was it like to collaborate with curators Arissana Pataxó, Denilson Baniwa and Gustavo Caboco Wapichana on the creation of the Hãhãwpuá pavilion? What prompted its conceptualisation?

GT: It was a very crucial, sensitive moment. Together with the curators, we have built a space where to understand and gather the amplitude of what Indigenous peoples represent, and discover the personal ways in which these peoples think of and name the territory. To ponder our participation in the Pataxó language, we also brought the Tupi language, hence the exhibition title Ka’Puera. There was a sensitivity in contemplating this multiplicity of languages so that people could realise how varied we are—how multiple the experience of living in this place can be—and take stock of the diversity of the territory that the Pataxós called Hãhãwpuá and we Tupi people call Pindorama. That each Indigenous community refers to it differently is very significant: it is a concept designed to raise awareness of the rich range of peoples present within the country. It also inspires us to strengthen our language and look after it, especially when foreigners approach us to learn more about our history, which has always been told from a universal perspective and never from the perspective of Indigenous people themselves. Participating in this year’s Biennale is a great experience that I believe will be useful for this erratum of history—for correcting that history through the point of view of Brazil’s numerous and manifold native communities.

GB: “Ka’a Pûera: we are walking birds” is centred around the history, heritage and ongoing challenges characterising the life of your community, the Tupinambá. What does it mean to be able to bring your ancestors’ legacy to the world stage via the Biennale?

GT: This exhibition is a vessel for us to echo the voice of our ancestors and highlight them, using every tool we have to counter a history in which we have had no participation if not an inferior or subordinate one. History owes us a lot, and this is an opportunity to bring a fragment of what we can tell about our own vast culture. The pavilion wants people to realise how much of our heritage is trapped on European ground—how much we still have to recover. The elders asked us to master the culture of the white man in order to try to understand him, so that we could find a way to retrieve what is necessary for, and belongs to, our people, so that we could guarantee this certainty, because this is our nature. And so that people could understand our demands—that not only we live in the territory, but that the flora, the fauna and all of the local biodiversity we are interconnected with survive too.

We can’t bring imbalance; people need to develop. For a long time now, there has been an understanding of what technology is and what its codes are. While there is an advance in technological development, it is a development that leads to self-destruction. Though the general mindset about technology is too rooted in people’s minds to be changed at this stage, it is important to consider that we need air to survive and water to satisfy our thirst. To have that, we must protect this safe harbour, the place that welcomes us and feeds us, as there won’t be a way for others to continue our legacy if we destroy everything around us. Our consumption of natural resources equals consuming human existence and life itself. We need to think about no bem viver e viver bem (“the good living and living well”), as my mum, Maria da Glória de Jesus, says, which means ensuring that nature remains standing.

GB: Launched a year after the restitution of one of the few surviving Mantos Tupinambá (“Tupinambá mantle”), the showcase displays a similar cape you have woven specifically for the Biennale. What symbolic and practical function do these mantles fulfil within your community?

GT: The Manto Tupinambá is not a static artwork. It is imbued with an agency and a spirituality of its own; it has a desire, a voice even. By listening to it, I can perceive and translate the mantle’s wishes to people. For us, these capes are ancestors. However, until recently, none of us had ever seen a mantle in real life, because all eleven remaining ones were kept in European institutions. We knew of their existence through the chants of our communities, but hadn’t had any contact with them. It was only in 2000 that one of these capes, which will be donated to the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro later this year, visited São Paulo for the Rediscovery Show: Brazil+500 exhibition. When Dona Nivalda, an ancient of the Tupinambá people, recognised the mantle while visiting the show, he convinced our community to go to court and try to prevent it from leaving Brazil. The case was tried and dismissed, and the cape returned to the National Museum of Denmark. Still, it did unite our people who had up until then been considered extinct by the Brazilian government. Though we were finally recognised on an official level in 2001, our battle continues.

GB: You are the first to have successfully recreated this mantle in present times. When did you set out to learn how to do it?

GT: I first saw a Manto Tupinambá in person while on a trip to France in 2018. It was then that I understood that these mantles were more than an antique craft piece. We were taught that objects can’t communicate. Suddenly though, I was in front of an ancestor showing me images from the past, interacting with me, speaking to me. That is when I decided to embark on a journey that would demonstrate how each of these capes—or ancestors—have a different function, how they complement each other. It was the manto itself that told me that they were originally woven and worn by women. I didn’t understand what it meant until photographer Fernanda Liberti gave me a book on the cover of which was a drawing of a woman wearing one of those mantles inside out. From there, I began to search, find and collect more and more images of women either dressed in or carrying the cape with them, continuing to seek access to more mantles to listen to them and look for evidence of what I had heard [from them]. My job is to listen to and decipher fragments of Tupinambá history that have been previously told by others and not by ourselves, so that I can put them back together and finally tell our whole story for ourselves.

When upon receiving the title of Doctor Honoris Causa Cacique Babau, [a leader of the Tupinambá people], was prevented from wearing the cocar at his graduation ceremony, I decided to create my first mantle as a political statement. To learn how to do it, I had to ask around and research memories of it within the territory. What helped me was a photograph taken by Lívia Melzi, which I found through Augustin de Tugny, a professor at the Federal University of Southern Bahia. The image captures the Manto Tupinambá in Basel, Switzerland, including its stitching. When I realised that my great-aunts and grandmothers, who are in their 90s, could still make that weave, I knew there was a way of recovering this technique. For our people, the importance of these capes existing, of us being able to retrieve chapters of our history by ourselves, also guarantees [that our territory stays in our hands]. Our land has not yet been demarcated: at the moment, we are having to confront the implications of the Marco Temporal, [the law that stipulates that the only territories to be recognised as property of Indigenous people are those native Brazilians owned from 1988 onwards]. The manto has existed for 400 years [in Brazil] against 300 years in Europe, so it is clear that Brazilians had this knowledge first and foremost. Making people aware of it is fundamental to preserve our rights and those of other Indigenous communities.

GB: What is the story behind this specific Manto Tupinambá?

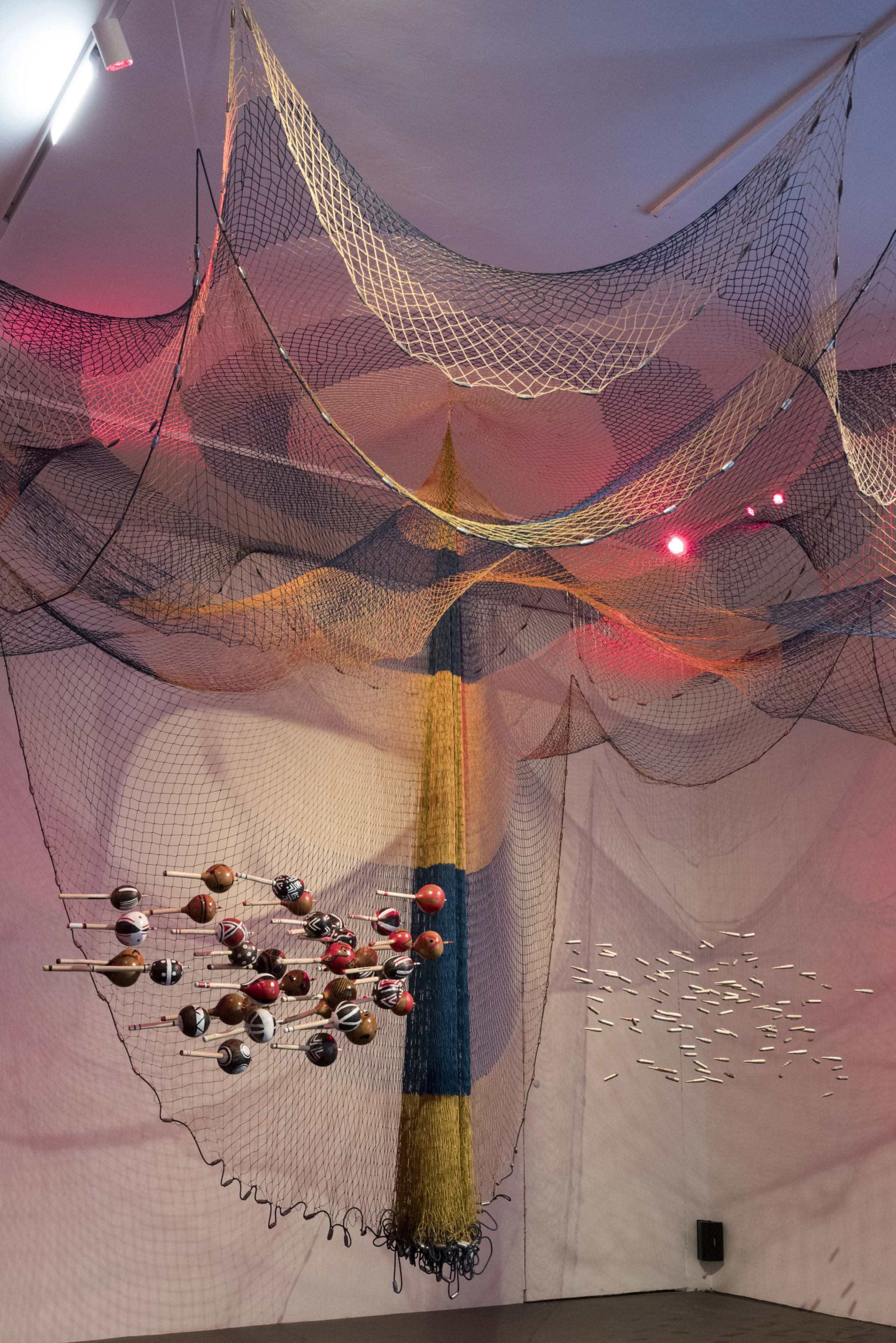

GT: The mantle creates its own personality; it guides how it wants to be made. Serving as the centre of the installation, the cape is composed of Guará feathers that I received, along with feathers that were collected naturally – as the birds fly, they come off and fall onto the beach. Many people volunteered to collect the feathers and send them to us, gathering 1,500 of them, which I then incorporated into the mantle. Comprising 4,200 feathers in total, the cape also features Macaw feathers, hawk feathers, pigeon feathers, and feathers from various other birds. We relearned the technique to put the mantle together, which was still mastered by my great aunts, whose skills and knowledge guided me while weaving. I was taught to make it with a single thread, which is what I did; I wove it without ever breaking it, then applied the feathers across different textures and layers.

GB: The Hãhãwpuá pavilion also presents a series of letters that were sent to other Western institutions currently in possession of the Tupinambá mantles, proving that the journey of restitution has only just begun. In doing so, the exhibition sparks a conversation on the colonialism-rooted dynamics of the arts and heritage sector. What are you hoping to achieve through this project?

GT: The letters ask for access to our ancestors—they are a bridge of contact for us to understand our own history. Through them, I was able to visit and listen to all of the mantles; I have just seen the last three here in Italy the week before the opening of the Biennale. There is still a lot we don’t know about Tupinambá and Tupi heritage kept in Europe, which makes this dialogue even more necessary. We don’t have the mapping of the Indigenous artefacts stored in Western museums, so it is key that these institutions grant us access to them. It is not just about the objects; it is about understanding the tradition behind them, about realising how the bodies of our ancestors were brought to cabinets of curiosities and why they need to be returned to their land. Museums have to overcome their fear of meeting me: the only way for us to understand [our history] is to establish a point of contact with such institutions. There doesn’t have to be conflict or resistance to this, but understanding.

GB: Speaking more universally, what would you like “Ka’a Pûera: we are walking birds” to symbolise? What is your vision of Hãhãwpuá for the future?

GT: I see the exhibition as an opportunity for people to absorb what Indigenous populations are in a respectful way. Essentially, it is us bringing to the audience our view of linguistic plurality, along with our diversity of people and techniques. Ka’a Pûera: we are walking birds is a space where, rather than judging, visitors are invited to familiarise themselves with a different culture. In the future, I would like people to start acknowledging Hãhãwpuá’s breadth and meanings as well as its various struggles. Whether one uses the language of art or the language of activism to push for that change, it is always a language—and language is always collective. “Collective” is probably the best word to describe what we brought to Venice with this presentation. Knowing that we didn’t get here alone, but thanks to our territory and the multiple ethnicities and languages existing in it, and that it is only through those that we formed this unity, makes me confident that this unity will persist for many years to come.

Words by Gilda Bruno