This Artwork Changed My Life is a fortnightly series of personal essays that share the stories of life-changing encounters with art.

Just over a year ago, all the staff in the university department in which I work were instructed to print a photo of their face, with a name and “a friendly tag line”, onto a template that was to be stuck on their office doors. The motivation was to make the quiet corridors of closed fire doors more approachable, which seemed fine in theory, but I couldn’t for one moment bring myself to do this.

Pasting a professional, public smile onto the tin can of my office that contained therein a much more tired, worse lit, far less eager to be seen, older and getting older human? It exhausted and embarrassed me in the particular way universities like to exhaust and embarrass their employees in the name of their conglomerate image. The instruction turned out to be like many directives from the management, where if you ignore the two-weeks of emails saying you absolutely have to do this, eventually nothing happens.

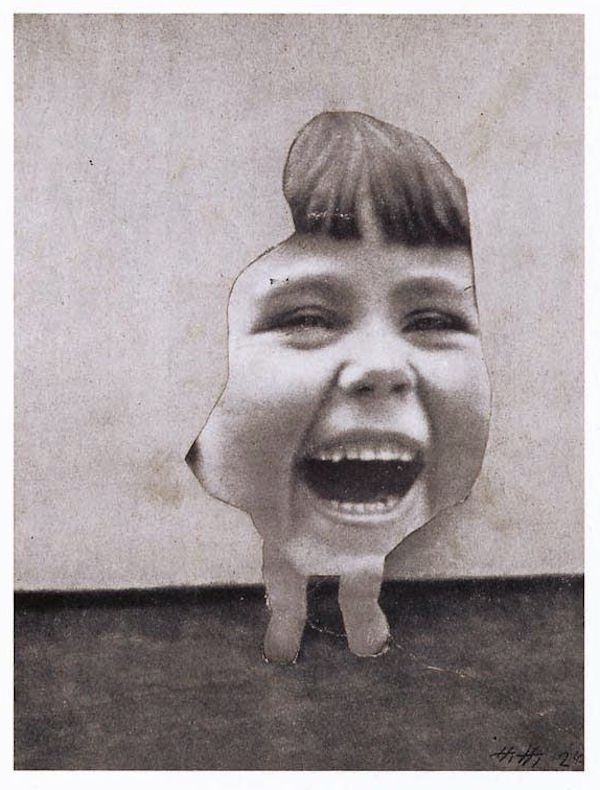

But in a kind of conforming protest I grabbed a leftover A4 handout lying on my desk and taped it to my door. The handout was a photocopy of Hannah Höch’s Unsere Lieben Kleinen (Our Dear Little Ones), 1924. The image is a small photomontage of a fragmented child, who is emerging from, or receding into, a monochrome background, and who is finding the situation just outside the frame extremely funny. I bought the same image as a postcard from the memorable Hannah Höch exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery in 2014 and liked it as a taunting mascot. The hilarity of the child’s expression suits the insolent image-making of collage, where something raucous is breaking through official surfaces. The day I stuck it on my office door was during the last week before I went on strike, in the last month before a pandemic, so it’s still there now, I think, marking an office I haven’t been to in a long while. Laughing at my absent face. To make matters worse, my face has all but become my office; my Zoom work-beacon, thrust at the screen and operating the day.

“The figure’s expression is both joyful and bizarre. Its dumbness, and cartoonish full-body-face, tickles me”

Höch’s work was formally introduced to me in the first year of my Art History degree, otherwise focused on Doric columns and Clement Greenberg, that arbiter of machismo modernism. Her rebellious pictures of screaming, laughing, crying, fleeing, kicking, dancing, fixed-in-motion figures connected up my ideas of aesthetic pleasure with the emotional response to a joke. In other words, my reaction to the compositions, where a combination of fragments generate a person or a face from incongruous forms, mirrors the new kind of sense that follows confusion in the process of finding something funny. Maybe even as funny as the straight-faced choice of ‘our dear little ones’ as a title. This to me felt like true satire. The mashed-up persons in Höch’s compositions were stuck rigid in the structures of their environment, while simultaneously ridiculing their circumstance.

As much as I can ever recognise how art changes my life rather than continues to adjust the language I have to live it, discovering the project of Dada changed my understanding of art as a method for contesting the artist’s immediate authority on a popular field, while rallying unconscious and readymade perceptions. I admire the way all of Höch’s interwar collages nuisance (among many things) the idea of a singular, grand work of art, so that not one work claims a command of truth. They also nuisance the very laws of images, the public image of women and our capacity for an easeful self image.

Funnily, it was this kind of re-mobilising of current and classic images that made me want to write and experiment with text. Collage is a tabletop craft, on a dial with writing and film editing as a practice that sits close to the domestic. Höch’s style, and many of the actual magazine images she cut up, were drawn from her time working for a garment pattern magazine making handicraft designs. In this mode of bringing ‘the kitchen knife’ to mainstream visual media, public iconography and advertising, I find the shared techniques of poetry, where the available materials for speech get reworked. Coming into poetry through a juvenile love of Dada helped me treat a line of poetry as collage of tonality. The anarchic figures in one of Höch’s montages and the so-called ‘speaker of a poem’ are subjects composed out of their surroundings, also mangled by them, then reconstituted as something or someone strange.

“In collage and in writing, every cut is protest, its join is satire”

In collage and in writing, every cut is protest, its join is satire. This would probably have been the point of the creative writing workshop I had made the printouts for, with the image that I later took as my own. Perhaps it was a class about remixed and appropriated materials, where the imported attributions of identity linger in the turf of the assemblage. Regardless of that, I liked how this laughing baby, comically poised on its finger-legs, looked on my door, and how it compared to what should have been a picture of me.

The figure’s expression is both joyful and bizarre. Its dumbness, and cartoonish full-body-face, tickles me. As a picture labelling my office it more than adequately represents the hysterical, worked-maddened, yet overindulged profile of any university’s academic staff. So as soon as this picture was up, I felt it was a good substitute for my face. It could either be laughing with joy or despair, with heterogeneous lines that are critically riddled into expressive edges of hierarchy, labour, personhood. I think that is what expression is, in terms of both creative gesture and facial expression: it is where multiple lines, incidental to each other, are read as a whole, whether that’s a face in an image or the voice in a text.

Most of all, I like the brattishness of Höch’s queer, feminist fragments. The squib-image of this and many of her seemingly off-the-cuff collages enact the fact that there are no neutral shapes, and the combinations of erroneous ones are even less neutral. Can I put my face to this door? Yes, but my face would only be ‘happy’ to do so as something mangled into the institution of the door frame, disarranging the hinge and handle, and giggling at its condition.

Holly Pester is a poet and writer. She has worked in sound art and performance with BBC Radio, Women’s Art Library and Wellcome Collection