Hannah Perry © Thierry Bal

It’s Monday and it’s Frieze Week, and Hannah Perry has just introduced her new exhibition, Gush, to a room full of the press gathered in the River Rooms at Somerset House—the end of the building where the walls are rough and ready.

Perry is primarily a filmmaker, who completed a BA at Goldsmith’s, but her technical prowess means she’s turned her hand to complex sculpting and sound works, designing camera rigs and even choreographing dance. Since showing at the Zabludowicz Collection in 2012, she’s mostly been showing her work in the US of late—for a time, she was living in LA—but she’s recently been back in London and working at studio at Somerset House, which she currently shares with Phoebe Boswell.

Gush presents five different mediums (though as she later explains, one is still due to happen and another to arrive). There are paintings, a large-scale installation, a video work and on Friday, there will be a performance, for which Perry is still in the midst of preparing. The final work completing the five-part show, a kinetic sculpture, is yet to appear—Perry’s Dad, an industrial metalworker with fifty years experience, is making it, and “He won’t be rushed!” she says. Her dad is also the reason she keeps coming back to automotive materials and motifs. “I’m drawn to the aesthetics around car culture for many reasons. It comes from a fascination with mapping the ethos of masculinity. I always wanted to explore how cultural constructions of masculinity emphasize masculine power and exclude women,” she explains. Those constructs, as the work reveals, are as harmful to men as they are to women.

- Rage Fluids (Künstlerhaus, Halle für Kunst & Medien, Graz) © Markus Krottendorfer

The possibility of creation from destruction is connected to some new directions in Perry’s aesthetics, visualized in the paintings, Liquid Language and Mechanism, and put into rigorous motion in the absent hydraulic sculpture, Bully. “I’ve been looking at car crashes from a metaphorical point of view: suspension, shock absorbers, collision, rupture and traumatized metal. It’s coming from this idea of crashing and colliding, somehow translating movement or dance to metal forms.”

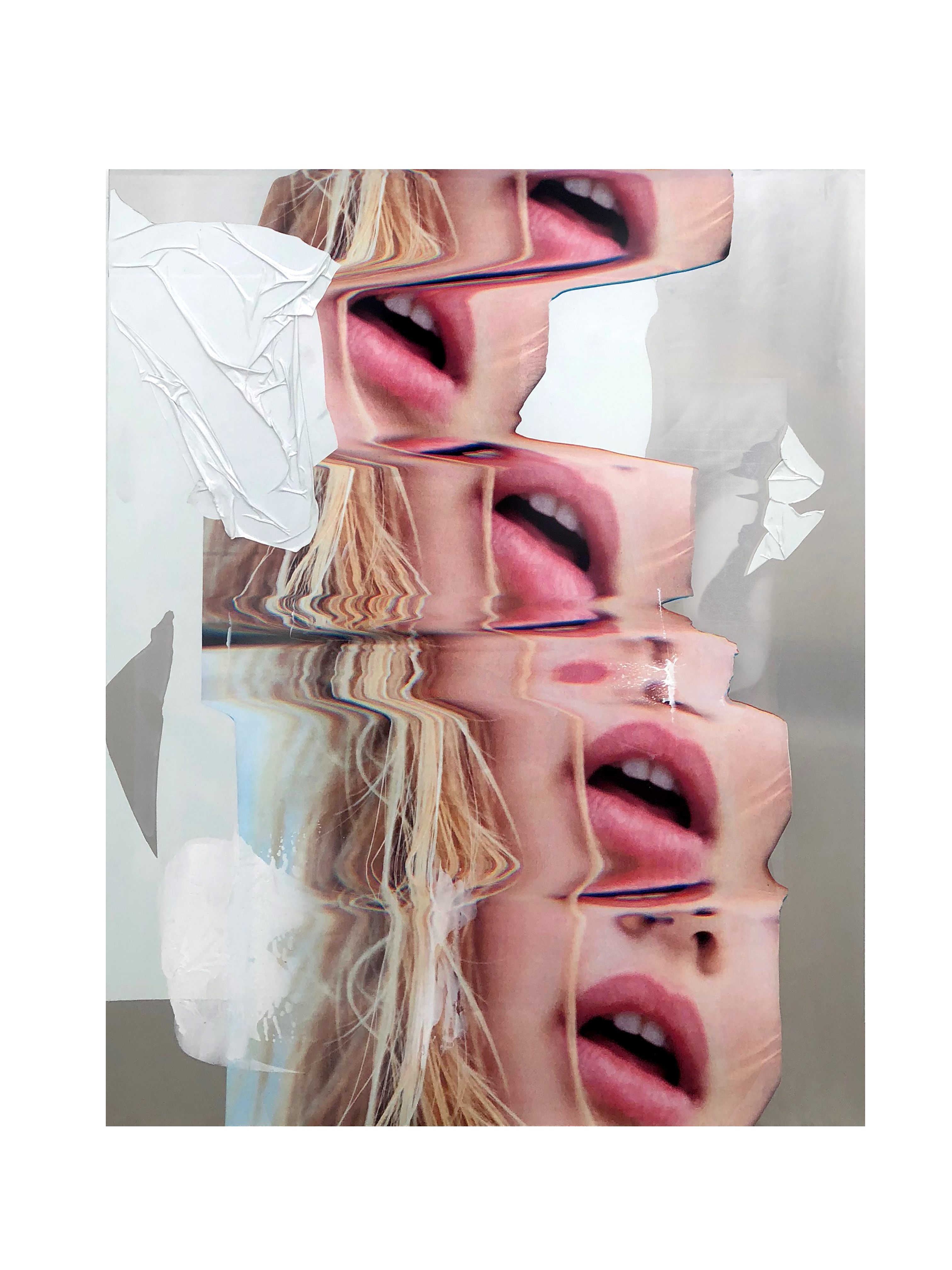

Light flooding in from outside strikes an undulating swathe of industrial car body wrap, installed like a skin that stretches across the room, from behind which subwoofers resonate, causing the surface to ripple and wobble, and the viewer’s image to blur and disintegrate. It’s a very real, nauseating feeling—an apt introduction to Perry’s latest film, Gush, in which half-naked bodies dance, faces flash up and dissolve, and the camera pans between empty apartments and bed sheets, Peckham and Los Angeles, car lots and nightclubs.

Sitting downstairs in the drafty cafe that neighbours the studios, Perry tells me more about the work she has just unveiled. It has has been part of a painful and personal healing process, following the suicide of her best friend, Pete Morrow, two years ago. A writer and poet who often collaborated with Perry, Morrow suffered from schizophrenia and was bipolar. His devastating death prompted Perry to dive deep into her own issues, she explains. “It was difficult to make but I wanted to make this work because it was important to me, and personally meaningful.”

The twenty-minute video work that is the centrepiece of Gush explores mental and emotional health, in a tangential, experiential way, creating dissociative and disorienting effects, in which the body and mind separate or obfuscate one another, in a synaesthetic way. It’s uncomfortable viewing—bodies never appear fully in the frame, images are deliberately distorted, pixelated and warped. It is comprised, as in Perry’s previous works, of tiny, rhythmic fragments, almost all footage drawn from Perry’s own archive, some shot on an iPhone. Other segments were filmed purposefully—such as an intensely moving scene shot more recently with a special 360-degree camera rig and trained dancers, who will be part of the performance taking place this Friday. It’s played on a concave curved screen that wraps 180 degrees around you—so that, again, you are never able to take it all in at once—your eyes trying to keep up as your body is immersed in moving image and sound.

Different voices merge with music in the film, so that there is not one narrative but a plurality of voices that are both reassuring and disquieting, a recreation of the symptoms of some mental illnesses. The script originated in Morrow’s diaries, given to Perry by his family, and includes contributions from students at the London South East College, the outcome of a series of workshops Perry lead, organized by Somerset House. “I can’t wait for them to see it,” Perry enthuses. Musical scores of soaring beauty and melancholy come from the London Contemporary Orchestra, alongside composers Mica Levi and Coby Sey. Collaboration is a cornerstone of Perry’s practice, especially important in a work like this, that interweaves the experiences of many for an audience who might have no idea what they’re coming to. Gush is a gaping wound.

It’s not the first time Perry has worked with issues around mental health—she used to organize an open-door meeting for people in her networks to discuss mental health; later this month she’ll be giving a talk hosted by Adwoa Aboah’s Gurls Talk.

When Gush is over, after twenty minutes of friction and confusing movement, it’s like stepping out of someone else’s mind; or the feeling of flashbacks to a long, heavy night of intoxication; or a lonely day spent down a rabbit hole on the internet. There are moments of poetry, pain and paranoia. It’s overwhelming, but it’s masterfully edited—and it can’t have been easy material to make or present, given that Perry was grieving for Morrow while making it. “I wasn’t prepared for the trauma or the horror of it all.” Perry reflects, when asked what the works in Gush mean to her and how it feels to see it in public. “This body of work is a way of understanding and looking at what happened with a sort of distance and in some sort of context, and in a lot of ways it also feels like collaborating with Pete again,” she adds. “I am just sad he isn’t around to see it.”

Gush examines mental health from inside and out. “Talking about mental health needs to be normalized,” Perry implores. When a leading cause of death among men under forty in the UK is suicide, she says, the time to talk about the crushing effects of silence and stigma around mental health and masculinity is now.