“I use nudity as a reference to historical works,” says Matthew Morrocco, an artist based in New York, whose series Complicit explodes our ideas of traditional masculinity. Tender, amorous and warm, the images show male bodies as soft and vulnerable—quite different to the rigid, muscular Kouros statues, the ubiquitous depictions of exemplary manhood in Ancient Greece.

When we think of male nudity, our ideas our still rooted in those ancient sculptures, Roman and Greek godlike figures, whose nudity proudly proclaimed both their imposing intellectual dominance and physical strength. Every part of the body was symbolic—a small penis, for example, represented a great mind and capacity for stoicism. Poses and postures presented the positive ideals of masculinity; war-like, brave, pensive.

“I think the first assumption is that the person in the picture is effeminate or gay because most people subconsciously assume that people who make these images are male.” Morrocco explains when I ask him how people usually respond to the images of naked men. “For a long time there was this concept among people who represent the male nude that pictures of naked men were an antidote to sexism or homophobia. But the problem is not that the world needs to see more representations of the male nude, but rather representations of other genders in positions of power as viewers and artists. Representation of the male nude, much like representations of the female nude, is not an antidote but a conduit to sexism and homophobia”

“I place my work in the context of the female nude,” Morrocco asserts. “The male nude is one of the most recognizable forms of Greek and Roman art, and in many ways the genesis of male sexual and physical prowess as special or domineering. I see my work as distinct from this narrative, representing something more sensitive and emotional.” The male nude in contemporary art has usually been constructed for a queer and homoerotic gaze and seen as subversive or erotic. Artists such as Juergen Teller or Antoine D’Agata are among the few heterosexual artists to use their own bodies to explore male nudity from their position as heterosexual men.

“Deciding to shoot male nudes came from a point of curiosity and dissatisfaction”

Paula Winkler‘s series Centrefolds is one example addressing, like Morrocco, the specific role of the male nude in the context of art and history to create narratives about masculinity and the male position according to the female gaze. “Deciding to shoot male nudes came from a point of curiosity and dissatisfaction,” Winkler tells me. “The male nude has been a genre in photography ever since its early invention, but mostly from a gay perspective. I do love those images, I always have, but I felt as if they were not directed at me and this bothered me. But it also fired my curiosity. It felt as if this particular area hasn’t really been discovered yet.”

“For me the gay spectator, for whom these historical images were made, is very present. So I took a chance in creating images directed at women like me,” Winkler adds. Her Centrefolds are traditionally masculine and their bodies are conventionally attractive, but interestingly Winkler also shows them as playful and performative, far from the disengaged male posturing of the classical art.

“I do direct a lot,” she tells me. “Naturally I’m dependent on what the model can or wants to do. Usually we start with a pose I have in mind, try out different things and work from there on. For the Centerfold series, I worked with men who are very confident within their bodies and have much control over them, so we were able to do quite ambitious poses.”

In C

entrefolds, her process contributes to the way we perceive these nude figures. “Photographing nudes is a very special affair, especially if you don’t work with professional models.” She notes. “Usually curiosity and even pleasure take over the atmosphere—and I mean pleasure not necessarily in a sexual way. Having someone’s exclusive attention in such an intimate setting can be quite a unique and enjoyable experience.”

“The men I photographed were very comfortable being naked,” Morrocco agrees, when I ask how men act when they stand in front of the camera without their clothes. For Winkler, who has photographed men and women, “in terms of performing in front of a camera I think the differences are not between men and women but between being used to being looked at or not,” she observes. “Maybe women and gay men are more used to being scrutinized and objectified than heterosexual men.”

Perhaps, as Winkler and Morrocco suggest, male nudity has been relegated as a subject in art by the discomfort of the dominant way of seeing—the heterosexual male gaze.

“I feel there can be more tension surrounding issues of sexuality when shooting male nudes as opposed to female nudes”

Aneta Bartos, the Polish-born, New York-based artist elates to this issue as a female photographer: “I feel there can be more tension surrounding issues of sexuality and subverting ideas about objectification, dominance, or just general comfort when shooting male nudes as opposed to female nudes. Even if there isn’t any sexual tension present, there is always the possibility of a thought or situation arising. I find men can be much more delusional than women.”

Bartos has photographed young men masturbating in hotel rooms, (Boys, 2012) and completed an acclaimed portrait series on her Father who is a bodybuilder, (Dad, 2013). These two series navigate two diametrically opposed relationships with men and male bodies, shedding light on archetypes of paternity and reversing the objectified, sexual nude as a female photographer.

“At the age of sixty-eight and having spent a lifetime as a competitive bodybuilder, my Dad asked me to take a few shots documenting his physique before it degenerated.” Bartos told me. “The original group of photographs I took inspired me to transform the idea into a long-term project. Dad is the embodiment of stability and strength and my childhood a representation of a worry-free world produced by my powerful yet gentle and loving father. His body plays a big role but it has more to with the fact that I was raised with a very unorthodox way of thinking of the body (as the daughter of a bodybuilder) in stark contrast to the more puritanical Catholic ways of thinking about the body in Poland at the time.”

Her Boys project, meanwhile, emerged from earlier work with female nudity and on female sexuality, “and perplexing aspects of women in gender politics, which made me more conscious of a decidedly patriarchic ideology in the arts and greater society,” she explains. “I had the urge to turn it upside down. I decided to push things further and challenge one of the most well-established male power phenomenon: the male gaze. The female was behind the camera and commanding the male to perform in the most sexual and vulnerable way—to masturbate.”

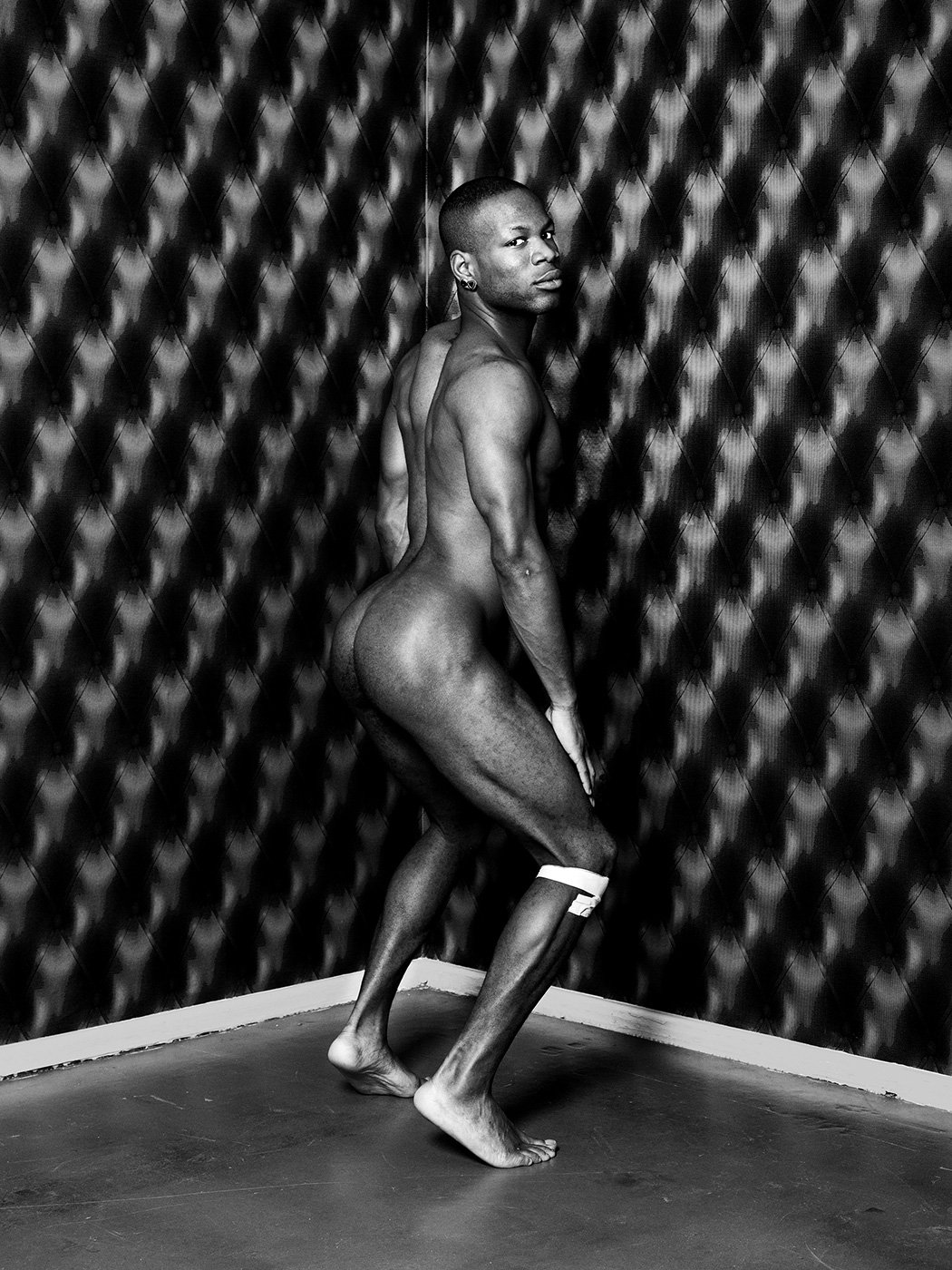

“The black male nude body in my work represents me at my most unguarded, honest and vulnerable,” says Buki Koshoni, on why he chose to photograph his model,Junior Delius, semi-nude for a new series of work, Batman/Blackman. “Only at this state of emotional and physical ‘nakedness’, I feel, can we connect with our true sense of self,” the Nigerian artist adds. “My view of the depiction of the black male body in a historical context is one of stereotype, both demeaning and one dimensional, born of fear and misunderstanding.”

Koshoni employs both nudity to reveal and props to create fantasy, exploring his model’s body as “a search of self, the truth of who I am…an exploration of my identity, both as a construct within society and my consciousness. The visual language of the black male body is being rewritten and I’m proud to count myself amongst the artists attempting to reconstruct this dialogue,” He adds. There is a tension in his work in the duality of the gaze, using the camera to look at oneself and at the way the world sees you, projection and reflection, inward and outward-looking.

“My view of the depiction of the black male body in a historical context is one of stereotype, both demeaning and one dimensional”

In the end, as Winkler puts it, posing nude for the camera, no matter who you are, is perhaps “about the act of transformation: body into image.” The male nude in the contemporary context is ripe for reinvention; what is obvious, though, is that many men are still far from comfortable with being looked at in this way. “In my observation men, as women too, love scrutinizing other peoples bodies—it’s pleasurable. But many hetero men are wary of someone watching them scrutinizing. I guess there is this fear of being judged by others as being gay. Isn’t that a pity?”