Contributor Bella Butler offers insight into the effects of the recent ubiquity of Matisse’s blue nudes in the form of mass-produced posters and posits a thesis related to their ‘sexiness’ (or lack thereof).

If you have entered any millennial or gen-Z’s bedroom, you have probably seen the minimalist blue Matisse print of a naked woman hanging on the wall. And if you haven’t, you’ve seen one of the millions of Matisse-esque posters sold at Urban Outfitters or other chains that offer the understated line drawings of the female body. There was a time when I looked fondly upon these styles of prints. I love nudity, specifically the nude female body, and I love seeing it celebrated. But in the past couple years, I have noticed my increasing aversion to anything that remotely resembles the aforementioned poster. In fact, I treat it almost as an abject object. And I think part of it has to do with the feeling that the proliferation, the utter ubiquity of this poster—and its spatial context—has done something that no naked ‘beautiful’ image of a woman ever has: de-sexualize the female body.

The female body has long been an object of sexualization—a sex object—a thing to be visually defined by the gaze of the other, against which there has been historic retaliation. Feminists have pushed for a desexualization of the female form in an attempt to break women free and make space for the possibility that a woman can be defined outside the breasts that hang from her and the children she *can* bear. And I am in favour of this. I have benefited from these movements myself. But when it comes to an aesthetic depiction of a woman that is, at its core, the result of an erotic gaze, the result of some concept of desire, its growing desexualization instils in me a kind of sadness.

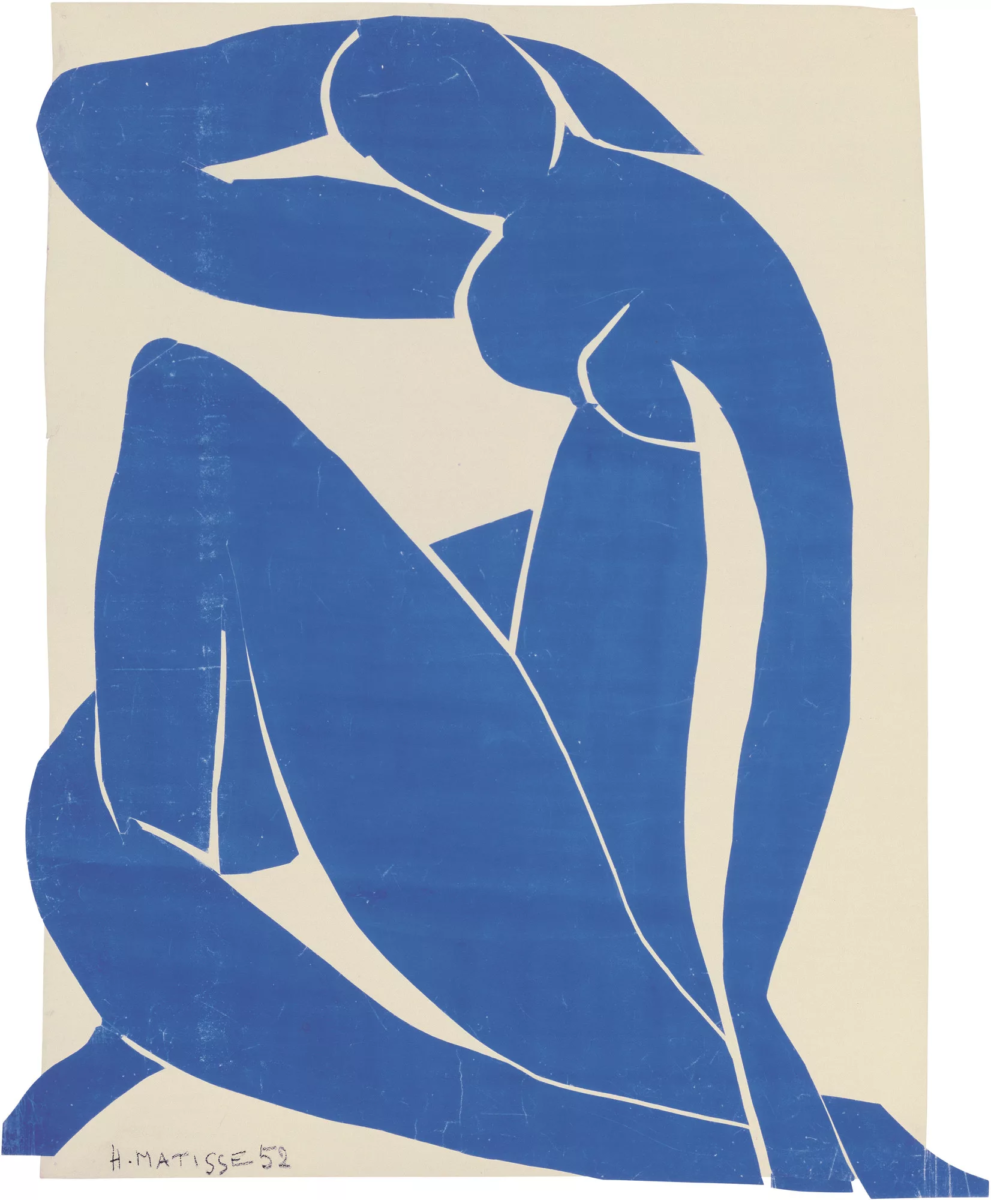

The ‘print’ to which I refer is simply a photo of one of Matisse’s blue nudes, as the original’s medium is not a ‘print’ but rather, what Matisse called a ‘cut-out.’ Matisse’s cut-outs comprise an oeuvre from the latter half of his life when he began looking for new ways to engage with colour and the line, as well as physically feasible methods to keep making art while confined to bed. As MOMA notes in their comprehensive description of Matisse’s cut-outs, “he described the process of making them as both ‘cutting directly into color’ and ‘drawing with scissors.’”

The instrument of the ‘scissor’ is an incredibly intimate one insofar as it necessitates both a disruption of and a consequent high degree of familiarity with the materials which it cuts. The act of cutting is a creative one, through an insertion into space and the subsequent production of space. Because of this, the agent behind the instrument has a tremendous kind of power and by extension, an equally intimate relationship to the materials which it disrupts and engages with. In the context of Matisse’s cut-outs, I would argue that this intimacy is heightened by the fact that this process of cutting is used to form a body: the female figure. Matisse’s naked women are therefore not only sensual in their naked appearance, but sensual as a direct result of their medium and the artist’s corresponding involvement.

Whatever one’s opinions of this relationship between sensual practice of the artist and sexual work as the product are, there is no doubt that it creates an erotic image. Matisse’s Blue Nude II (1952) pictured above is technically sexual. There is movement, there are implied but vague references to tabooed parts of the body, and there is the seductive colour blue that he uses which omits a coolness, which creates a distance between the viewer and the cut-out that leaves the viewer yearning for more. If one looks closely at the high quality image of the original piece (figure 1 of this article), you can read the narrative of its creation: the necessary sensuous relationship between the artist and the pieces of cut out paper fastened to the wall or canvas; there is a kind of materially defined (or Walter Benjamin defined) ‘aura’ due to the visually evident physical relief between the cut-outs and the surface they sit on.

But here’s where we get to my aforementioned sadness. The photo of the piece—originally titled Matisse’s Blue Nude II—that is mass produced through its distribution as a poster for interior decor, has lost all of these sensuous and sexual qualities. This is true whether you revere the original or not. In fact, I would go so far as to say that when I walk into a room where I see a blue naked cut-out hanging on the wall, I am turned off. The sex is drained right out of me. The image is flat and the woman I see on the wall is no longer a woman, is no longer even a sex-object, but social currency drained of its life through its ubiquity.

I say ‘social currency’ because it has departed from its original value as a piece of art in itself—one that is tied to an artist and a viewing experience (museum, gallery etc.) —and has begun to derive value from the mere fact that others have it. Or rather, it derives a certain value because it epitomises a particular aesthetic that has become attractive for living spaces. To force a linguistic metaphor down your throat, the poster has a role within a given ‘style’ that serves a similar purpose to that of ‘jargon’ within any given school of thought. It is a social short-cut, and a nuanced one at that.

—

Is it too extreme to call ubiquity a form of abuse? Artistic abuse? That poor blue woman lies in stockpiles in Urban Outfitters warehouses because of her ‘beauty,’ when really she is being flattened out, squeezed of her juices, and made a symbol for a kind of minimalism-meets-feminist-aesthetic off of which commercial artists across the world will base their line of 15$ dorm room decor. There is nothing sexually radical about hanging her on your wall, because she has become asexual through the very act of hanging her on your wall. If you want her sexiness back, don’t align her with pastel coloured sheets and other commercial boob paraphernalia. If you want her sexiness back, don’t make her look so damn clean. If you want her sexiness back, roll her back up and let her hide for a few years.

Words by Bella Butler