An archetypal British tradition, no holiday was complete without a visit to the local newsagent to peruse the rotating photo rack of gaudy landmarks or crowded beach scenes to send back home to awaiting friends and family. But in the age of Instagram, has the affection for picture mementos been made redundant, or is there still a place in modern society for the humble postcard?

A precursor to the captioned “take me back” bikini selfie, the postcard was arguably the social media of its day. Immediate and informal, the telegraphed messages that adorned the backs of picture postcards have much in common with the modern text or tweet. Postcards were a cheap and convenient means of communication, at the turn of the twentieth century, that now offer a peek into the past. The distinctively gaudy colours, combined with the depiction of ordinary life in a lost era, has imbued these inconsequential holiday souvenirs with social, historical and artistic interest to a modern yet nostalgic audience.

THREAD. #Lockdown must be getting to me because I saw this great photo of Brighton in 1971 by Graham Cosserat (via @aflashbak) & decided to track down every postcard on the stands. It’s the nearest many of us will get to a holiday this year. #LockdownPostcardChallenge pic.twitter.com/pMlCrZOZho

— Richard Littler (@richard_littler) May 27, 2020

“Postcards were a cheap and convenient means of communication that now offer a peek into the past”

Graphic artist and screenwriter Richard Littler decided to spend his time during lockdown tracking down every postcard from a 1971 photo by Graham Cosserat. He documented his progress on a popular social media post. When asked about this niche undertaking, he explains, “many people were probably aware they wouldn’t get away on holiday this year and the Twitter thread offered the opportunity to do something as mundane as idly browse a postcard stand at the seaside. As the photo is old enough, nostalgia also probably plays a part—the memory of a childhood holiday when times perhaps seemed to be more innocent and worry free.”

According to a recent study, more than 40 percent of millennials aged 18 to 33 consider “Instagrammability” when deciding on holiday destination. Now common practice for the influencer industry, the use of geolocated pictures and appropriate hashtags can be traced back to the democratisation of the tourism industry, largely thanks to the sending and receiving of postcards. By the 1930s, coinciding with the birth of advertising and modern capitalism, postcards had become a way for holiday-goers to boast about their travels, as well as a means of free visual promotion for tourist companies.

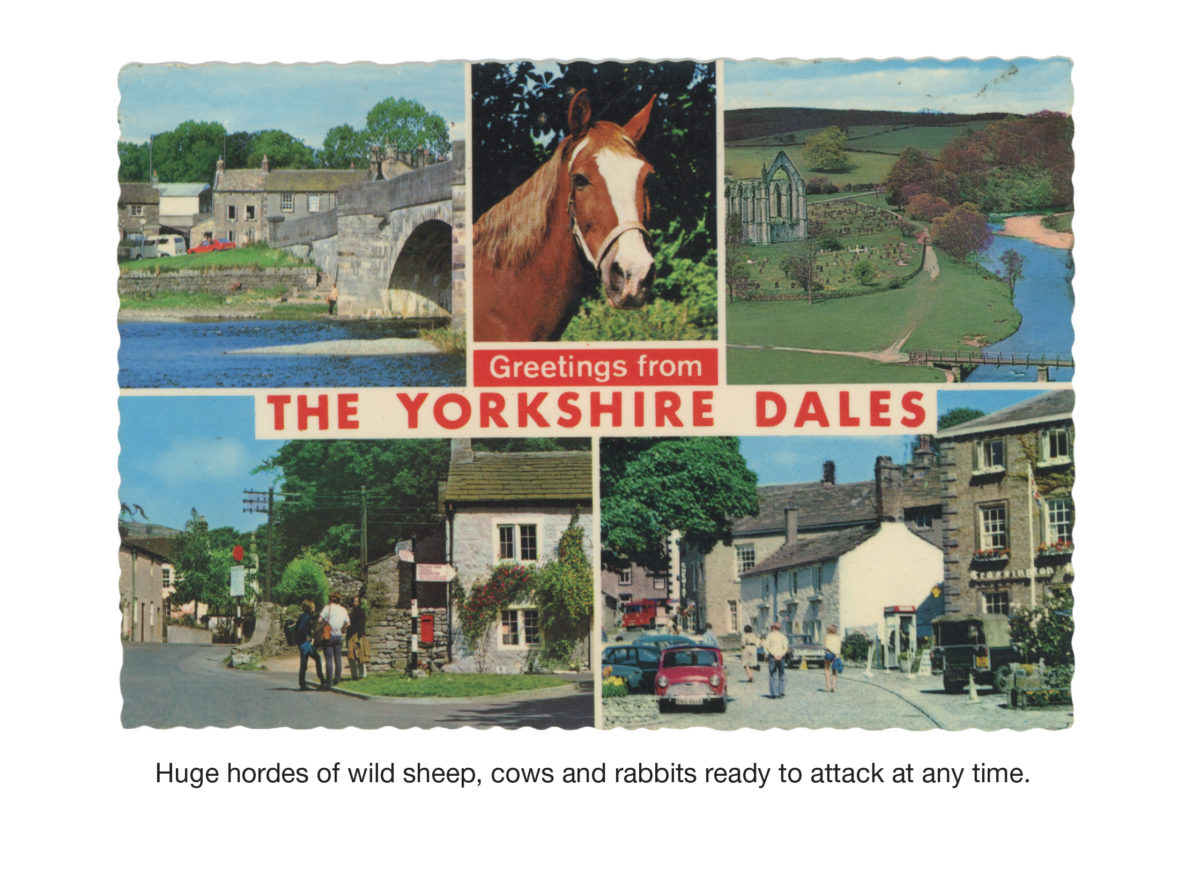

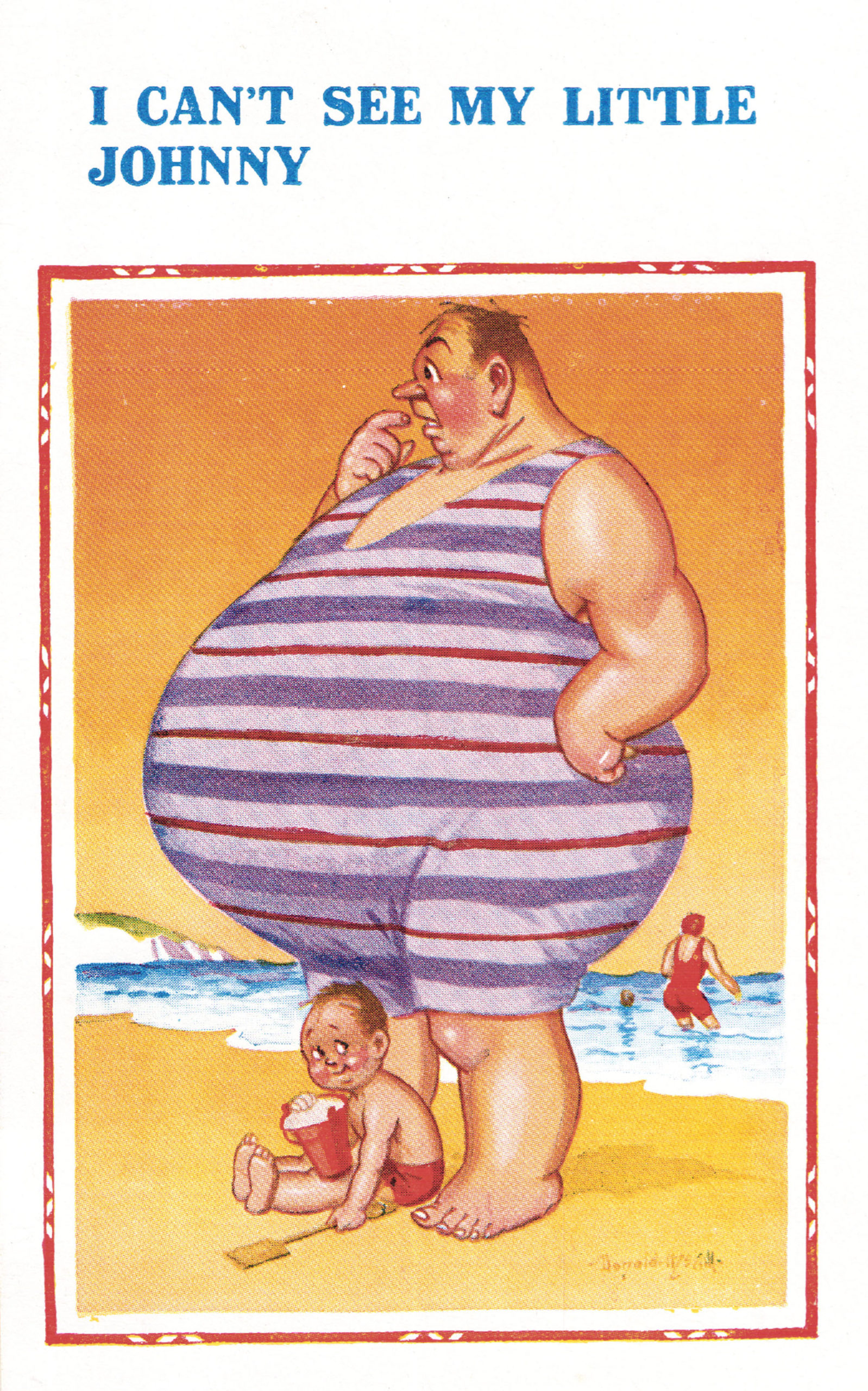

With the idea of a holiday abroad a distant dream for the many still in lockdown, the British seaside has seen a revival as a cheap and convenient getaway for local tourists, and has recently been rebranded as a “staycation”. Synonymous with seaside souvenirs are the highly collectable cartoons of Donald McGill, which reflect the heyday of the postcard industry. Having produced an estimated 12,000 paintings during his career, his subjects included drunkenness, double-entendres, sex and politics. Highly controversial during the conservative era of the early 1950s, some of his tongue-in-cheek designs were banned for indecency. They are now appreciated by collectors both for their artistic skill and keen sense of social observation, fetching up to £1,700

in auction.

In a 1941 essay

on McGill’s work, George Orwell wrote, “Their existence, the fact that people want them, is symptomatically important. Like the music halls, they are a sort of saturnalia, a harmless rebellion against virtue. They express only one tendency in the human mind, but a tendency which is always there and will find its own outlet, like water. On the whole, human beings want to be good, but not too good, and not quite all the time.”

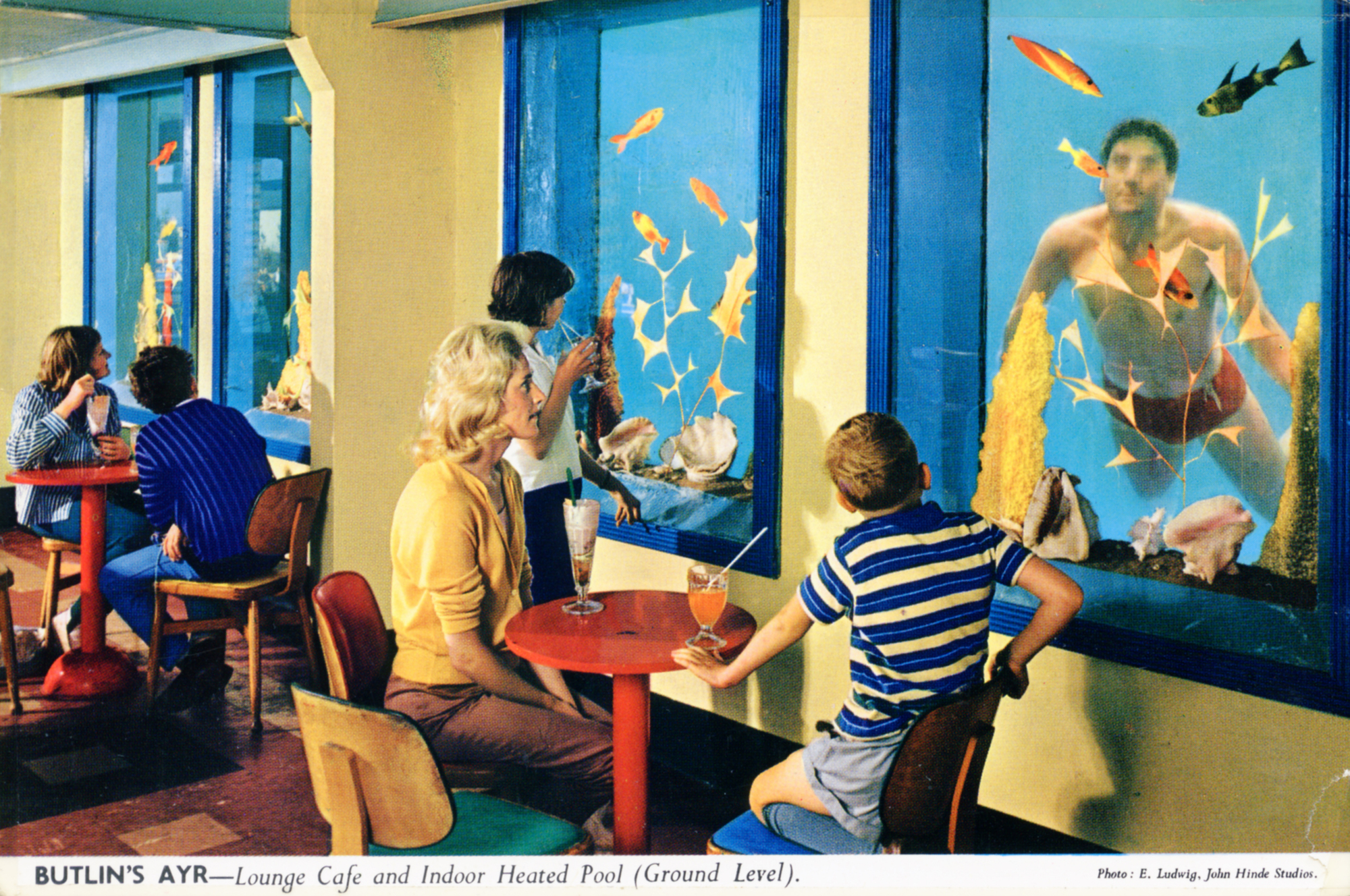

Now protected as a Grade II Listed historical site, 1936 saw the opening of the first ever Butlins Holiday Camp in Skegness, prompting countless picture postcards with the advent of cheap package holidays. Combining a heavy dose of nostalgia, sentimentality and kitsch, John Hinde, a failed circus entrepreneur, was highly influential in the art of postcard photography in the late 1960s and 70s with his depictions of Britain’s holiday resorts.

He set up John Hinde Limited, one of the world’s most successful postcard publishing companies, and trained a studio of photographers, including David Noble, Joan Willis, Elmar Ludwig and Edmund Nagele to reproduce his visions. Saturated colours and an idealistic and nostalgic style characterise his images of camper cottage complexes, luxurious ballrooms and crazy golf courses. A pioneer of colour at a time when “serious” photography was black and white, each photo staged a large cast of real holidaymakers in large narrative tableaux that idealised the experiences of ordinary British tourists.

In modern Britain, postcards and postcard collecting are decidedly antiquarian pursuits. Researchers in the humanities, arts and social sciences have left the study of postcards, called deltiology, to the deltiologists, and the leading journals in the field are primarily price guides for purchase. While photography underwent a shift to be reclassified as art in the early twentieth century, postcards remained excluded from the realms of “high art”. However, as there has been a shift towards a more inclusive frame for the study of visual culture, the previously relegated medium has been recast as an economic, social and cultural phenomenon that combines both the verbal and the visual.

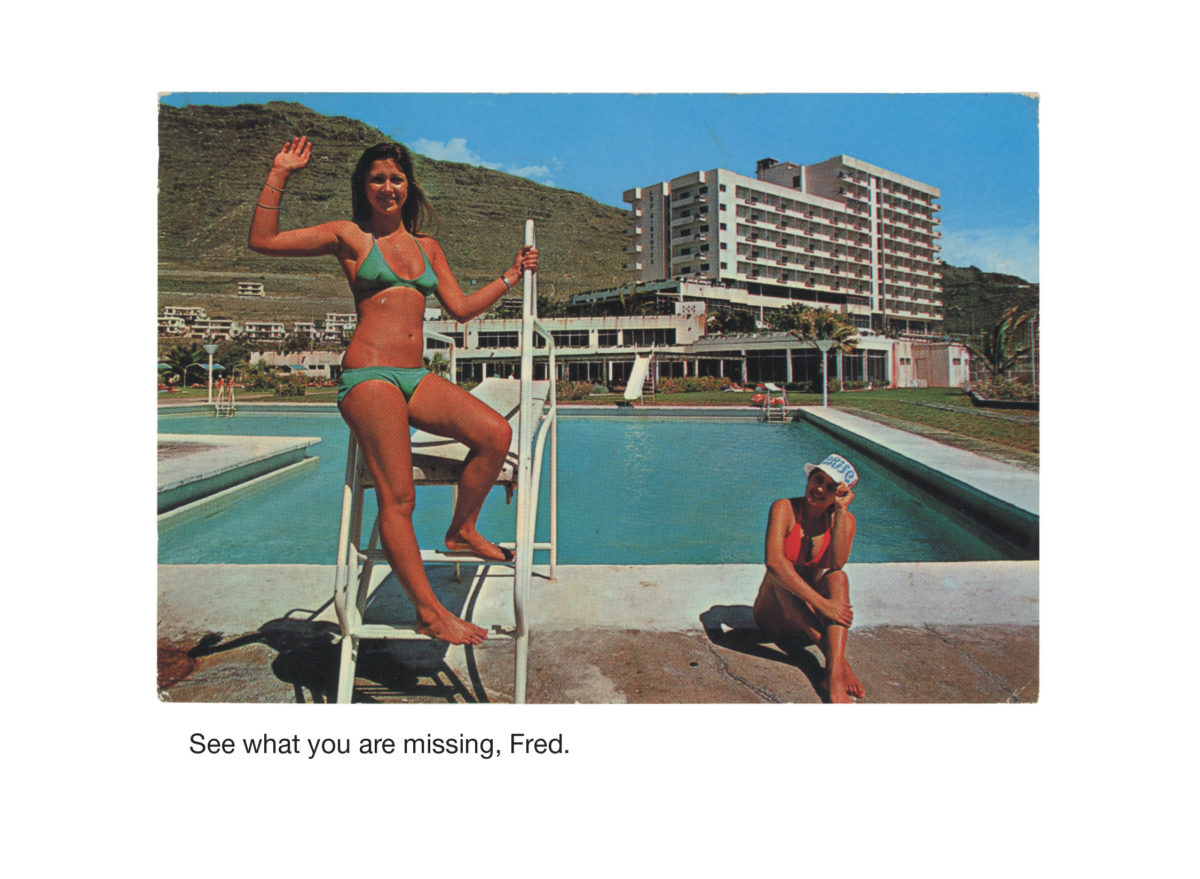

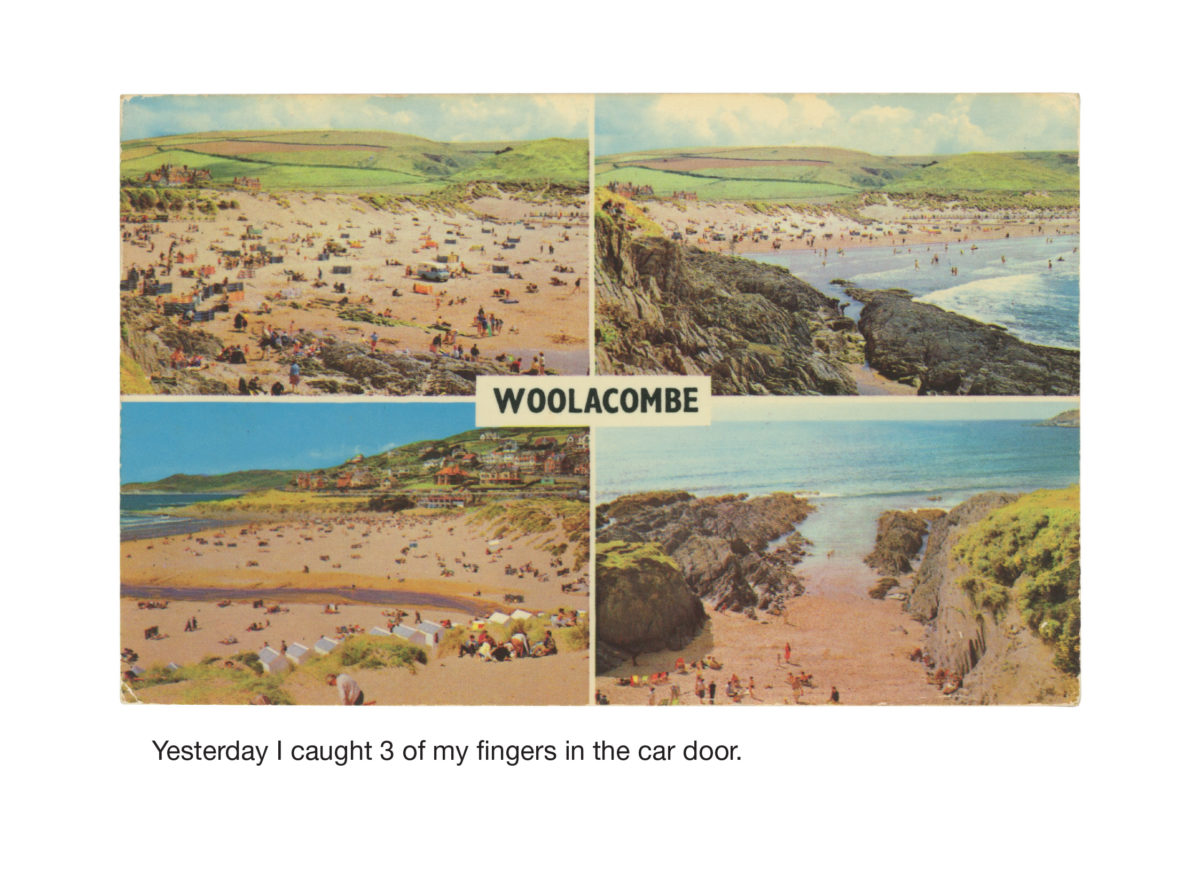

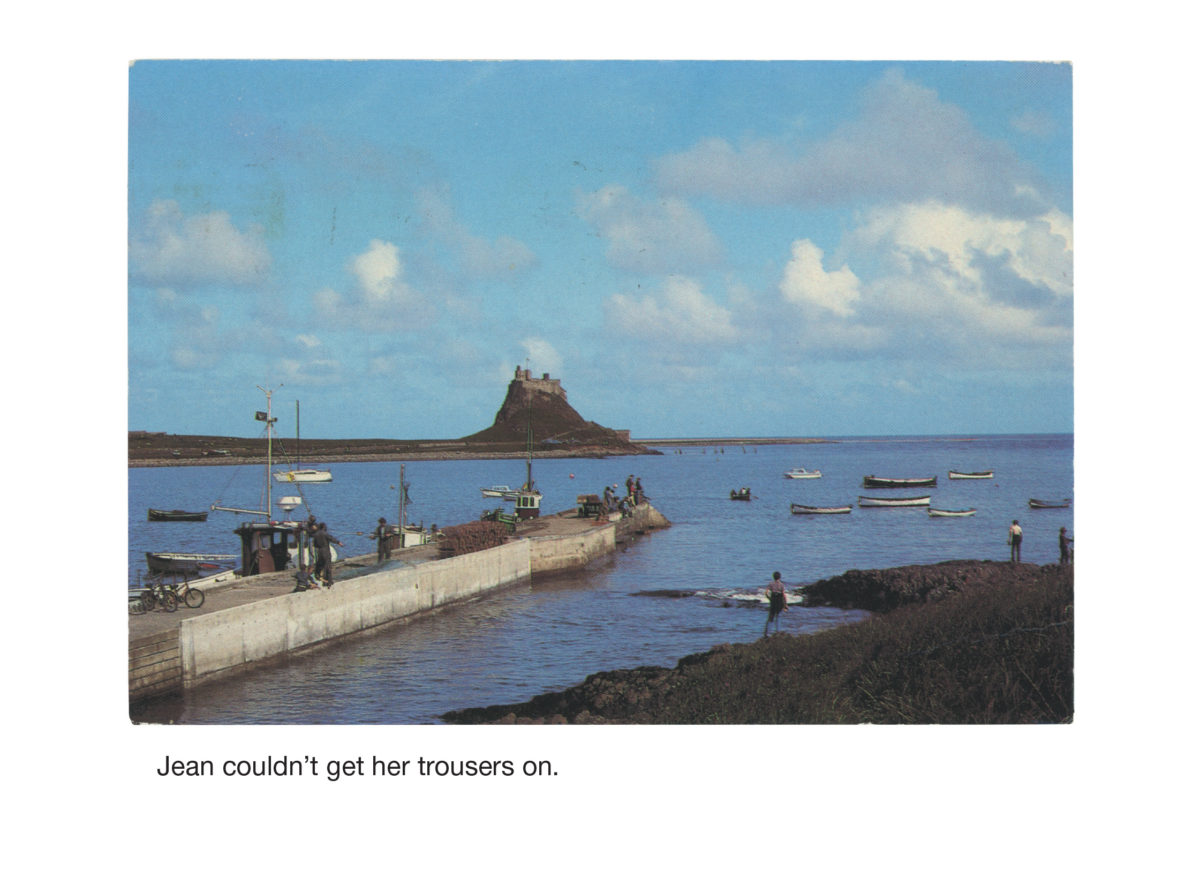

“I enjoy the opportunity to eavesdrop on people from fifty, sixty, a hundred years ago. It’s fascinating to have such a direct window into people’s concerns and emotions,” Tom Jackson explains. The author of Postcard From The Past and owner of the popular Twitter account, PastPostcard, Jackson’s curated anthology shines light on micro-stories, mishaps and tantalising one-liners that provide a small window into the past.

“I’ve been thrilled by how people have taken my whole postcard message project to heart. I very much started the Twitter account as an experiment, an art project, to see how these postcard images and little bits of postcard messages would look and feel in a digital space. What would it feel like to have a postcard correspondent from 60 years ago appear to communicate directly with you on your phone? It turned out other people connected with them and with what I was doing, and it took off. Now I have around 88,000 followers on Twitter, I’m prepping the fourth series of my podcast Podcast From The Past and working on another—all for some old postcards.”

“As an interdisciplinary image-object, the postcard embodied the intersection of geography, economy, history and identity”

Described as a “Lilliputian hallucination of the world” by surrealist poet (and collector of postcards) Paul Eluard, popular postcards were also collected by Andre Breton and Salvador Dali. They were similarly described by Dali as “the most lively document of modern popular thought, a thought so profound or so sharp that it eludes psychoanalysis.” For these artists, surrealism and everyday visual culture were intimately conjoined, and they were fascinated by the capacity for postcards to express the collective unconscious.

Postcards also inspired work by Hannah Hoch, Herbert Bayer and Man Ray, who reused them or quoted them in their art. The industrialisation of images at the beginning of the twentieth century represented a nodal point in the relationship between art and photography. Dadaist photomontages were sometimes directly made on postcards and posted, rejecting the aesthetic of ‘high art’ and embracing the industrialisation of images and new print media.

Nostalgic in tone and intent, the popularity of postcards reflected a changing society. As an interdisciplinary image-object, the postcard embodied the intersection of geography, economy, history and identity, epitomising the complex field of visual culture and straddling the distinction between high and low art. While social media may have overridden its functionality, the collectability of the postcard remains a testament to its enduring charm in an increasingly digital world.