Hayv Kahraman, born in Baghdad, became a refugee in 1992 when she arrived in Sweden aged eleven. She remembers her mother flushing their falsified passports down the toilet after a month-long journey that took them through Jordan, Ethiopia and Yemen. Kahraman and her family were amongst three million Iraqis who were forcibly displaced during the period between the Iran-Iraq War and the Gulf War – almost twenty percent of the population at the time. Today, Kahraman lives and works in Los Angeles, after her family finally settled in the United States.

The things that refugees choose to carry across borders are invested with an emotional significance that deepens with time and distance. Like a talisman or relic, the object is a synecdoche for loss and survival, and its value lies not simply with its function, but its capacity to represent a connection to both the actual and the intangible meanings of ‘home’. In the single suitcase they carried, Kahraman’s mother packed a mahaffa, a handheld fan woven from palm fronds that is referenced in Mesopotamian imagery as far back as the eighth century, and is still used and made in the same way throughout the Gulf region. The mahaffa appears throughout her most recent series Mnemonic Object, sometimes carried by the central figure, and often referenced in woven segments of the canvas surface that have been carefully split and re-sutured. Like a memory prompt, she bids us to look through the object to reach an understanding of her individual experience within a collective national identity.

Is this how she thinks about memory, as an archive that can be catalogued and stored—a real place to be revisited? “Yes, that was definitely the ignition to those works; the necessity to archive and solidify my own history. Living in the US, there’s this constant cover-up of who I am, or was, as an Iraqi. I needed to ensure that my biography wasn’t being erased.” She has spoken about how the specific Iraqi refugee experience is somehow exacerbated by the ‘weight’ of history surrounding Mesopotamia as the mythological seat of our universal human heritage.

“‘Any Iraqi you speak to, there’s a strong sense of this utopian past – the present and the future can never live up to that past. I think it’s ingrained, and it’s something I have struggled with.'”

“Any Iraqi you speak to, there’s a strong sense of this utopian past—the present and the future can never live up to that past. I think it’s ingrained, and it’s something I have struggled with. I think it’s universal to some extent; I’m sure your mom has those tendencies too, to refer back to the ‘good old days?’” True, perhaps—but whilst in Western Europe our parents might be nostalgic for the post-war boom of the 1950s and 60s, in Iraq, sectarian tensions dominated the decades following independence from British Empire in 1932. In reaching beyond the successive traumas of multi-nation invasions, regional wars and colonial occupation to a glorious ancient past, there is a safer place, however blurred the outlines, wherein to construct a unified collective identity.

Important, too, is her use of the word “artefact” throughout the series. It makes me think about one of our primary shared spaces for storytelling, the museum—where the traditional politics of display often reinforce hegemonies of knowledge that appropriate and erase indigenous narratives. “Yes! A lot of the dialogue around these works has been around migration, but the significance of that word and the role of museums has not been picked up much. For me, there are so many problems in visiting, for example, the British Museum and trying to understand the existence of those objects in the Museum and also my personal relationship to them. It’s such a loaded space.”

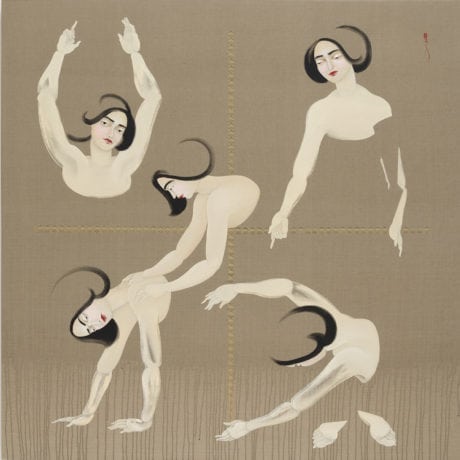

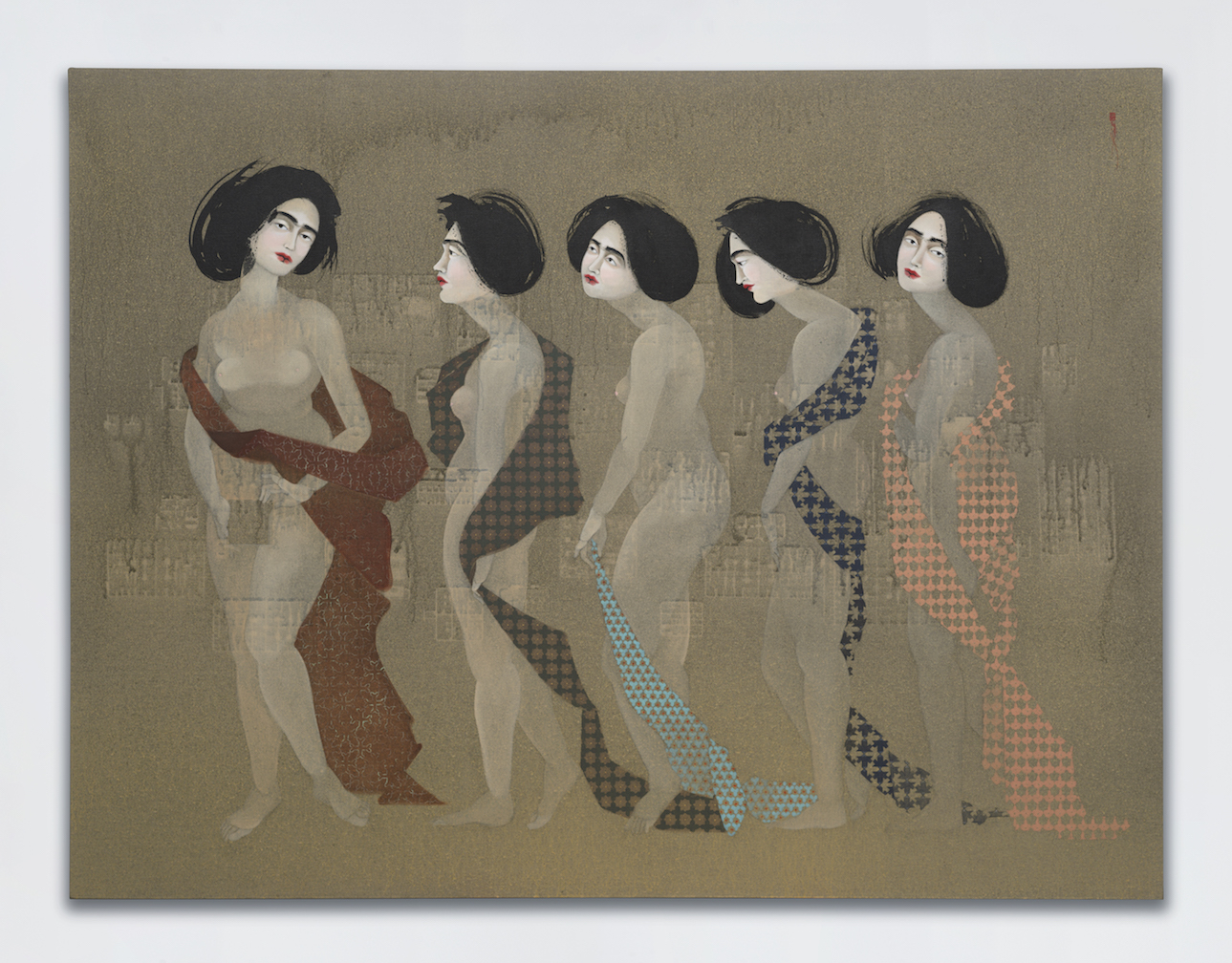

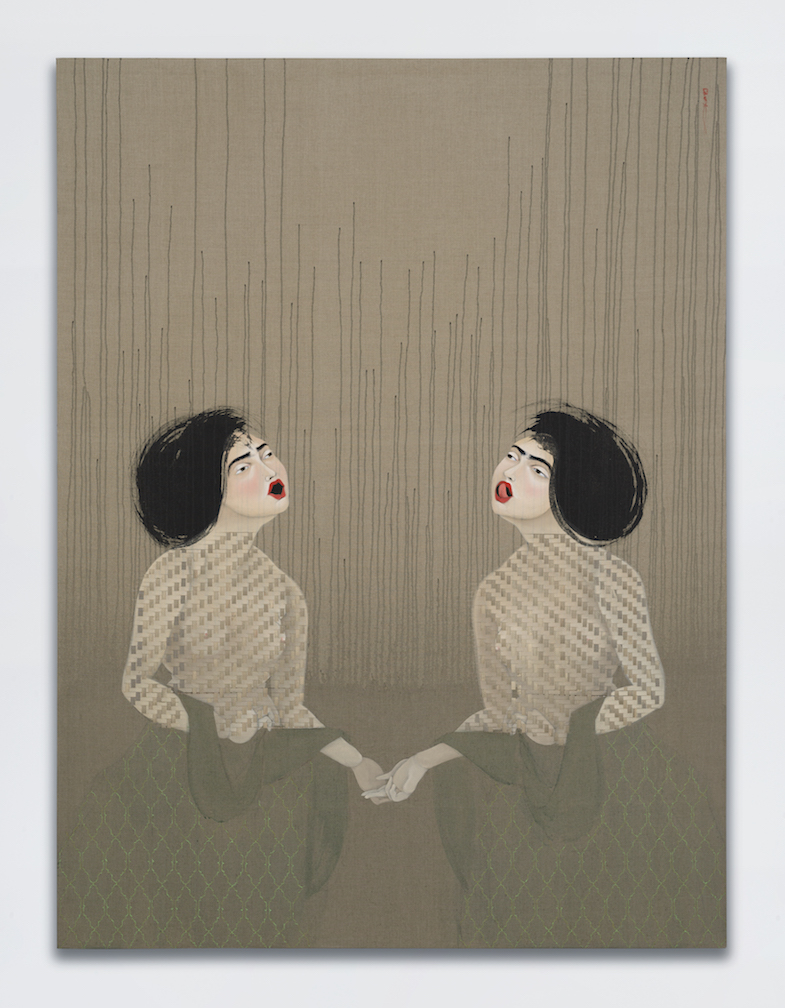

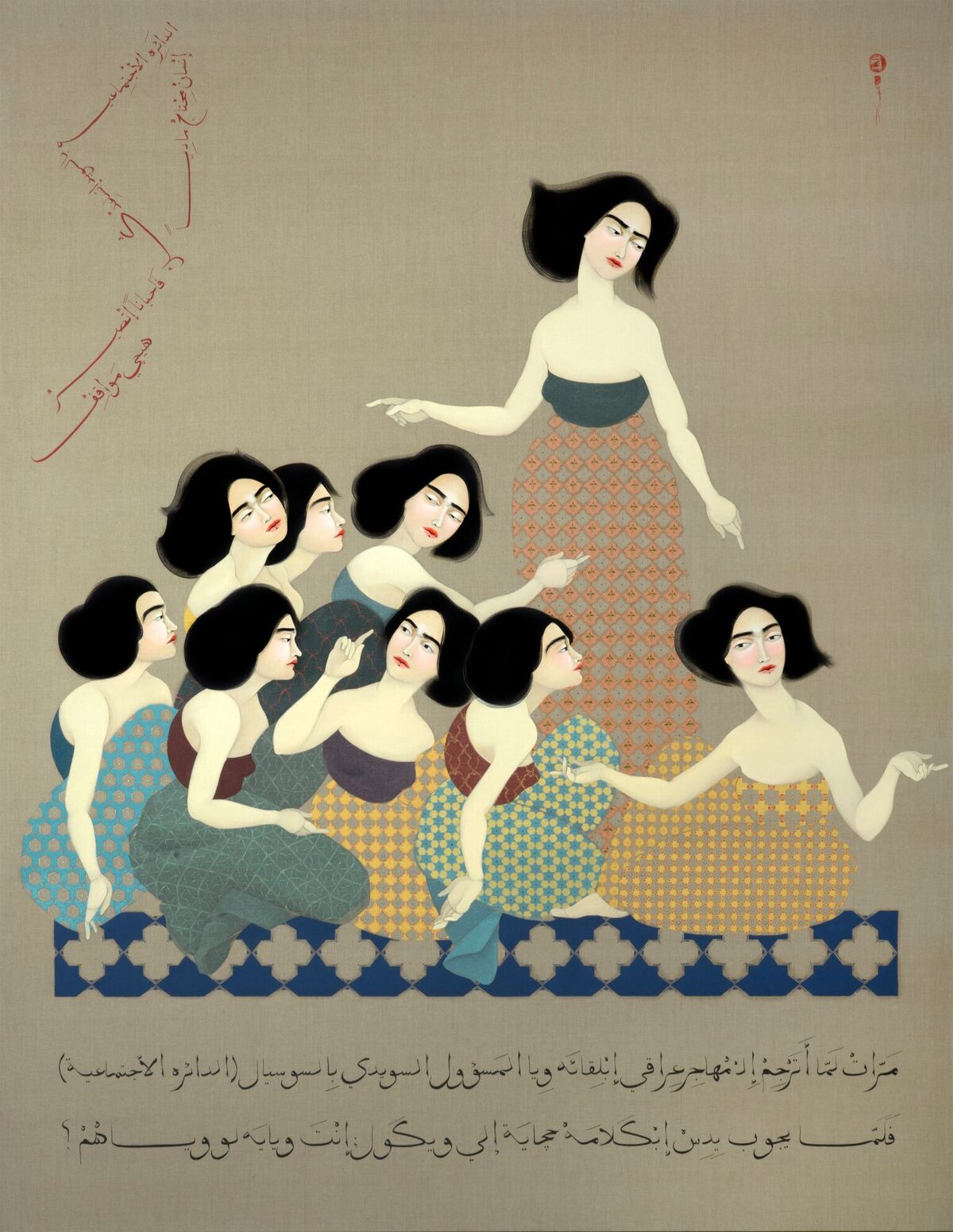

The figures that people her work bely this sense of burden, floating unbound by perspective against the bare linen canvas, painted with careful, premeditated strokes. ‘I don’t like error. I learn a lot when something doesn’t go right, but it’s a very uncomfortable place for me. I think that comes from living a chaotic life, fleeing the war and having such an unpredictable future for a long time. I need to have order. It becomes an obsessive thing, psychologically’. She studied design at the Accademia d’Arte e Design in Florence, and the formal practices of Renaissance painting echo in the posture and temperament of the figures, all replicated versions of herself, rendered from a 3D scan of Kahraman’s own body—an alter ego named ‘She’ or ‘Her’, appearing sometimes alone or huddled in groups, not shy but somehow withholding; refusing.

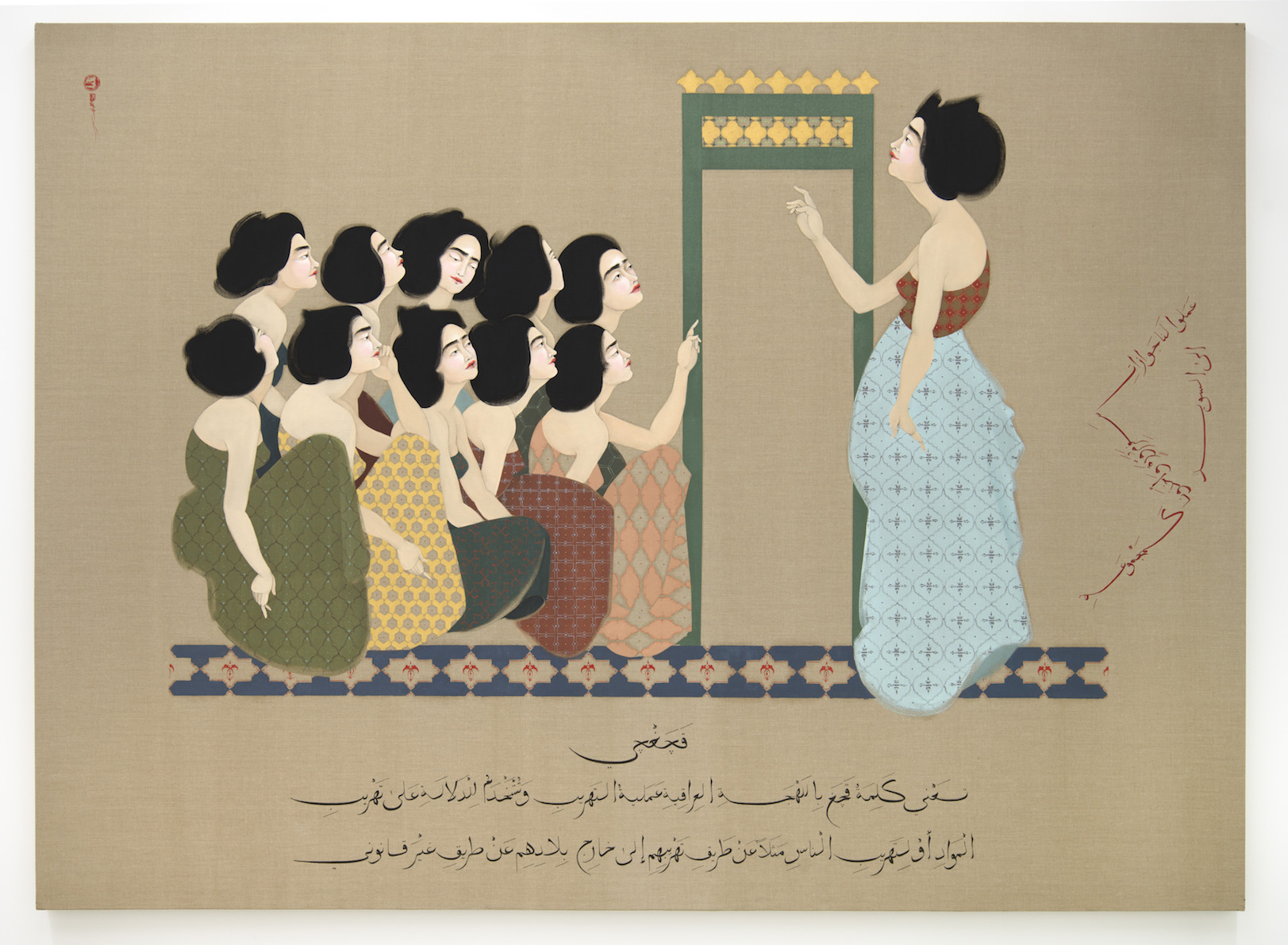

This summer, she is showing works from her How Iraqi Are You? series at the V&A Museum after being nominated for the Jameel Prize. In this group, jokes about language and assimilation are made alongside references to a 12th century Baghdad manuscript, the Al-Hariri Maqamat. The performance accompanying her work for the Prize took place in the Raphael Gallery, and Kahraman is excited by the disruptive potential of placing “our brown bodies amongst these white statues.” Performed alongside five collaborators, all women living in the diaspora, the ‘choreo-essay’ is an expanded version of a text published in 2015, Gendering Memories of Iraq, and which she has updated and performed in spaces across the US and Europe.

“‘I am very aware that my viewer is most likely going to be white, and somewhat privileged. How can I mediate images of distant suffering bodies to this white audience?'”

How much does she consider the viewer when she makes her work? Does she intend the act of looking to be painful, and in sharing that pain is there any potential for healing on either side? “This is why I paint these Renaissance bodies, these white bodies. It’s going to be easier for the viewer to connect to that body, and in that connection, hopefully there is going to be an uncovering of other layers in the work. Things like memory, history and erasure. It is definitely something I think about when I place my work in the gallery space…I am very aware that my viewer is most likely going to be white, and somewhat privileged. How can I mediate images of distant suffering bodies to this white audience?”

“When I walk into my studio, I realise I am building my own army of women. It is an army.”

I am surprised by how directly this impacts her creative choices. It is sad that gallery goers are probably more capable of sisterly empathy with figures that share their skin colour, and this brings us back to the connection between bodies and objects. In the US and Europe, images of cultural destruction throughout the Middle East region are obsessively reported by the media, seemingly resonating more strongly than the massive human losses of the conflict. For Kahraman, coping with this reality from the vantage point of her life within the invading nation has been a curious process of disconnection and creation: “She emerged at a point in my personal life when there was the need for me to have Her, and to give Her my agency…I see us as a collective force. When I walk into my studio, I realise I am building my own army of women. It is an army.”

All images courtesy of Defares Collection