What do your houseplants say about you? Are they perky or limp; in bloom or bare? For many, a cactus is the plant of choice, while the perennial cheese plant is also favoured. There is a houseplant boom quietly taking root with the millennial generation who, bereft of the financial security and prospect of ever becoming homeowners, have directed their attention towards more achievable goals. Plants brighten and add colour to a space, as well as introducing a personal touch.

Earlier this year, the New Yorker ran a piece titled “The Leafy Love Affair Between Millennials and Houseplants”. It featured a “plantfuencer”, whose plant-care YouTube channel, Plant One on Me, boasts upwards of 80,000 followers. She explained the trend like this: “It’s this wonderful hobby that we have somewhat control over, especially because we don’t have back yards or places to call our own, really.” The movement is showing no sign of abating; the #houseplants hashtag on Instagram has been used over 2.5 million times.

View this post on Instagram

Windowsills: the precious real estate of houseplant lovers. 📷: @nelplant #houseplantclub all-star 🌟

Plants, of course, look great onscreen—an important consideration at a time when social media has enabled us to invite acquaintances and strangers alike into our own homes via the pictures that we upload. What was once a private domain, which a handful of close friends might visit, has become public property via Instagram—albeit a highly curated version of the home. The app has transformed how people decorate, and sales of home interiors products are on the rise.

“Plants look great onscreen—an important consideration at a time when social media has enabled us to invite strangers into our own homes”

This year alone, a glut of books on the subject of plants and flowers as interior decor have emerged, from Blooms, a weighty tome published by Phaidon, to Wild at Home, which offers tips and guidance on styling a verdant indoor space. More than anything, plants offer an outlet for creativity and self-expression, which might sound holistic but is of particular value in an age when the success of a personal brand can be quantified through likes and shares in the ruthless attention economy. In the digital era, we are desperate to assert our own point of difference even as we appeal to the popularity mechanisms of the masses—and what could be more idiosyncratic or personal than a plant?

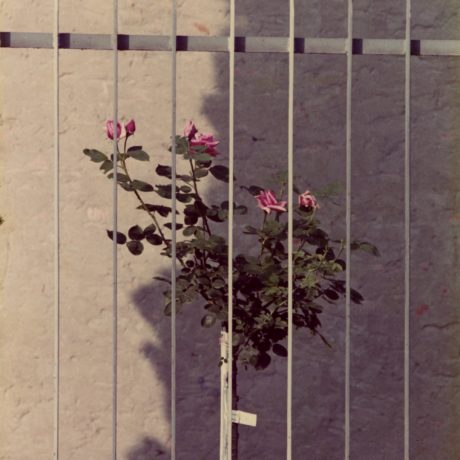

The subtle (and not-so-subtle) self-expression embodied by greenery in and around the home is the subject of a series of images by Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri, titled Colazione sull’Erba, or Breakfast on the Grass (inspired in name by the famous Edouard Manet painting). Shot between 1972 and ’74 in Modena, Ghirri turned his lens not on the wilder reaches of nature but on its quieter interactions with the built environment, photographing pot plants, well-kept lawns, cypress trees and trimmed hedges. The series was published as a book, as Ghirri originally intended, by MACK Books earlier this year, while an exhibition of the series has just opened at Thomas Dane Gallery in London.

“Ghirri turned his lens not on the wilder reaches of nature but its quieter interactions with the built environment”

There is a muted intimacy to these frothy flowers and sensuous green tendrils, shown creeping over windowsills and under panes of glass. Front gardens conjure stories of their unseen owners, decorous and prim, while unkempt shrubbery suggests absent (or absent-minded) residents. Gates and windows form gridded structures that emphasise the contrast between natural and manmade forms in Ghirri’s rigorously structured photographs. The formal consistency of the images in this series serves to highlight the personalised differences between them, to be found in the glimpses of green amidst the concrete and the brick.

Unlike Generation Rent today, the residents of Modena were able to display these splashes of living colour beyond just the interior recesses of the home; particularly useful in the pre-Instagram age. As they venture outdoors, it is inevitably the larger and more elaborate plants that are the most eye-catching—and none more so than the bold examples of amateur topiary.

The art of topiary dates back to classical antiquity, when yew and holly were cut into fantastical, architectural and animal shapes with knives and shears. It was later revived during the Italian Renaissance in the strictly symmetrical gardens of the Medici family. In the seventeenth century the style became popular across the grand gardens of Europe, with lollipop trees and spiral-shaped hedges adopted as high art. In the decades since, topiary has declined—largely due to the intensive attention required to maintain a well-trimmed hedge.

Over on Instagram, however, topiary lives on in the popular imagination, with hundreds of thousands of images uploaded under the hashtag #topiary. Photographs of Northern European formal gardens populate this feed, documenting the madcap creations of royalty and aristocracy of yore. There is something enduringly endearing about the representation of fantastical forms via a simple hedge. That someone would invest the time into a pursuit so grandiose and so fleeting is just absurd enough to be brilliant. After all, an object or animal that has been either scaled up or down holds a fascination for many since childhood, when our toys are most frequently representations of the real world, from our stuffed dinosaurs to our toy cars.

“Topiary turns heads; it is a form of outsider art in full bloom“

Topiary is a dying art, like many other folk crafts such as patchwork or crochet. In the age of hyper-convenience and overwork, to spend time on an independent pursuit purely for the pleasure of the process itself is increasingly rare. As an article published in the New York Times last year argued, “It’s time to divest hobbies from productivity. Their value lies in more than their relationship to work.” In the face of neoliberal global forces, it is hardly surprising that we find ourselves mimicking the capitalist cycles that govern our world as we look for endless means by which to maximize our creative output.

Today, topiary is uncommon outside of the grand gardens of stately homes; and yet, when it does appear, it has the power to unite a neighbourhood and attract visitors. Topiary turns heads; it is a form of outsider art in full bloom. Just a few streets from my home in London sits a giant topiary dog, lounging outside its owner’s house as if waiting patiently for them to return home. It has been snapped and uploaded to Instagram hundreds of times, becoming as much a symbol of the neighbourhood as any other, more permanent, architectural landmark.

Further north, a trio of elephants march cheerfully around a corner; they are the creation of Tim Bushe, an architect and topiarist who has taken his hedge cutters to a range of London front gardens. “The hedge sculptures take about three or four years to properly form their shape. I mainly cut animals but I’ve also started doing figures. Last year I started a Henry Moore reclining nude in Holloway, but it’s headless at the moment and the boobs are in the wrong place,” Bushe told Time Out last year.

There is a age-old appeal about the collision of the manmade with the natural, whereby plants are potted, hedges are pruned and lawns are trimmed. In living alongside nature even within the built environment of the city or the home, humans find themselves able to reconcile their modern-day existence with the quieter rhythms of the world. A cactus might not change much day-to-day, but it represents all the aspiration, longing and frustration that are so often bound up in our lives. Like the snatches of greenery that Ghirri turned his camera towards, plants offer a release—a moment of silliness or calm—amidst the chaos.

Luigi Ghirri: Colazione sull’Erba