Espinho is a small city on the Atlantic coast of northern Portugal. It’s a sleepy kind of a place, overshadowed by its much better-known neighbour, Porto. Belgian photographer Vincen Beeckman stumbled on it by accident back in 2016 when he was travelling around Portugal in his van, but he’s returned many times since. In particular, he’s been back to the Bairro Piscatório, a tiny fishing community at the heart of the city. The Bairro isn’t traditionally picturesque, but for Beeckman it has a beauty all of its own.

Close-knit and often related, the people in the fishing quarter uphold a way of life that’s remained essentially unchanged for hundreds of years. They still use the arte xávega, a type of trawling that involves using wooden boats to send nets out to sea, then haul them back to shore with the catch. Once the hauling was done by horses; now it’s done by tractors. Otherwise, it’s basically the same.

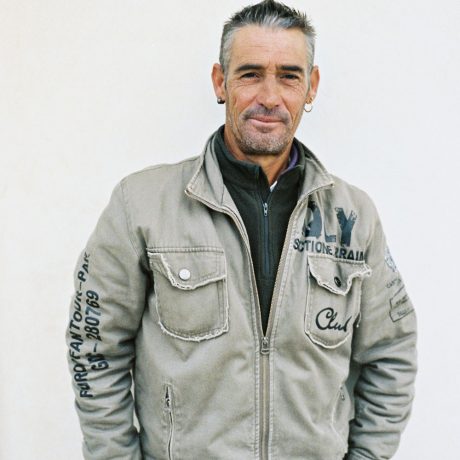

“They have two wooden boats, which are very colourful on the beach,” says Beeckman. “The first time I went I made some images, so I then wanted to go back and share them. I rented a little room in the Bairro, and I started to become more interested. Each time I’ve gone I’ve rented the same room and I’ve worked in the streets, just walking, stopping, meeting people, having a beer, discussing a football match sometimes. You can see the energy between the people.”

This energy is what attracted Beeckman, the people’s sense of affinity both with each other and the natural world. Arte xávega is labour-intensive, exposing the fishing crews to the elements and the strength of the sea, and giving them a healthy respect for both. It’s also sustainable, allowing fish stocks to remain at healthy levels, unlike higher intensity, apparently more successful modern methods. The crews in the Bairro Piscatorio also know each other intimately, having grown up together. They have a different relationship than, say, an employer and employee in a more industrialised port.

“This energy is what attracted Beeckman, the people’s sense of affinity both with each other and the natural world”

One of the local fishermen tried working in Porto but decided to come back because, while the money was better on the company ships, working them made him feel like a slave, he told Beeckman. At least in Espinho he’s living and working with friends. And if there’s an ethos in the Bairro that resists commodification (of the fish, or nature, or themselves) it’s an ethos that can be seen in other ways too, in the DIY signs people have painted, or the outdoor barbecues or decorations they’ve improvised.

Life is hard and money is scarce in the fishing quarter, but perhaps it also has something that’s been lost elsewhere. “It’s not beautiful, and there are problems,” says Beeckman. “But it’s a very strong community. It’s a kind of old-school place.”

“He aims to work alongside the communities he photographs, not zoom in, get a story, and leave”

Beeckman is attracted to communities like the Bairro, places that have lessons for bigger, slicker societies. He’s worked with the people (often migrants) who live around Brussels’ Centraal Station, for example, giving them cameras so they could show their interpretation of their fun-loving, close, though often homeless group. He’s also working on an ongoing project with 20 individuals in a psychiatric centre, combining his images with their drawings and writings to show their creative, heartfelt approach.

He aims to work alongside the communities he photographs, not zoom in, get a story, and leave. Each time he goes to Espinho he takes images from the previous trip to give away to the communities they document. He’s been there so often, he’s now welcomed in. Two years ago he staged an exhibition in the Bairro, glueing his photographs up in the street. Now that he’s made a book

of his images, he chose to launch it in the community, not in a bookshop or museum.

“I took a trolley from the supermarket and just went in the streets in September,” he says. “One guy came to help me find people and translate, and we just went door to door giving books away. Everyone was happy and it’s like a big family, so the word soon spread. I received messages afterwards from people who had missed it, and had to send more copies.”

“I took a trolley from the supermarket and we just went door to door giving books away”

A museum launch will follow, but for Beeckman it had to go to Espinho first. Future copies will emphasise this auspicious start, because they’ll be wrapped in papers showing an older lady in the Bairro receiving her copy. Like the people in the fishing community, Beeckman still has to make a living, but like them too he also demonstrates how to value something more. In a social media age of instant gratification, it is a vanishingly rare quality.

“I used a shopping trolley because it was practical, I didn’t have a way to carry all the books around,” says Beeckman. “But afterwards I liked the symbolism, of using a trolley not to buy things but to give them away.”

Images courtesy Intimate Structures and the artist