“Photography is not real, it is a technique to reproduce and reinterpret reality. Art is not real, art is fake. Art cannot reveal the truth.” I’m speaking with Hiroshi Sugimoto, the Japanese photographer who turned seventy this year. We’re at the Enoura Observatory, part of his own foundation, located in the picturesque mountains near Hakone, which is about eighty kilometres away from Tokyo.

“A view of the sea is one of my first memories from childhood,” he tells me, “it is reminiscent of the view of the gulf from the Sagami Bay here in Odawara. I was lucky to be able to purchase this piece of land, which overlooks this spectacular piece of nature. Enoura Observatory is all about my artistic production, everything concentrated in one place.” The sea has long been a source of inspiration for the artist, first emerging in the Seascapes series that started in 1976. As Sugimoto recalls: “The view of the sea is something we share with hundreds of former generations and we will continue to share with several future generations. It is a human way of sharing memories and forming feelings that connect us with one another, and the process goes far beyond an individual’s country of origin and national identity. We all share memories, the place of origin is of secondary relevance. In truth, I believe that Seascapes represents the foremost essence of my art.”

- Left: Gemsbok, 1980; Right: Polar Bear, 1976

For an artist who uses such a wide range of methods and techniques, photography remains his medium, and it was a medium that took off in earnest when he began studying at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California in 1970. “I didn’t want to continue my father’s business or become a salaryman,” he says. “Since I was very competent with my hands and at craftsmanship, I decided to study art abroad.” Self-taught and perseverant from a young age, as a child Sugimoto was particularly attracted by making models. “As a kid I didn’t like to socialize and I spent a lot of time in my room enjoying craft-making with traditional materials such as wood. I was able to build and assemble things independently and I was particularly interested in making models using traditional methods of construction. I am a handyman. Because of my enthusiasm for making models of trains, taking photos of real locomotives was initially a supporting activity to perfect my modelling skills while looking at accurate images in the process of reproducing the trains. At the age of twelve, my father gave me a professional camera as a present, a Mamiya 6 with 6×6 images, and I learnt to use it all by myself at that young age. I learnt all the functions, mastering tricks little by little. I find enjoyment in learning advanced manual techniques, despite the initial challenge.”

“The view of the sea is something we share with hundreds of former generatons and we will continue to share with several future generations”

Boden Sea Uttwil, 1993

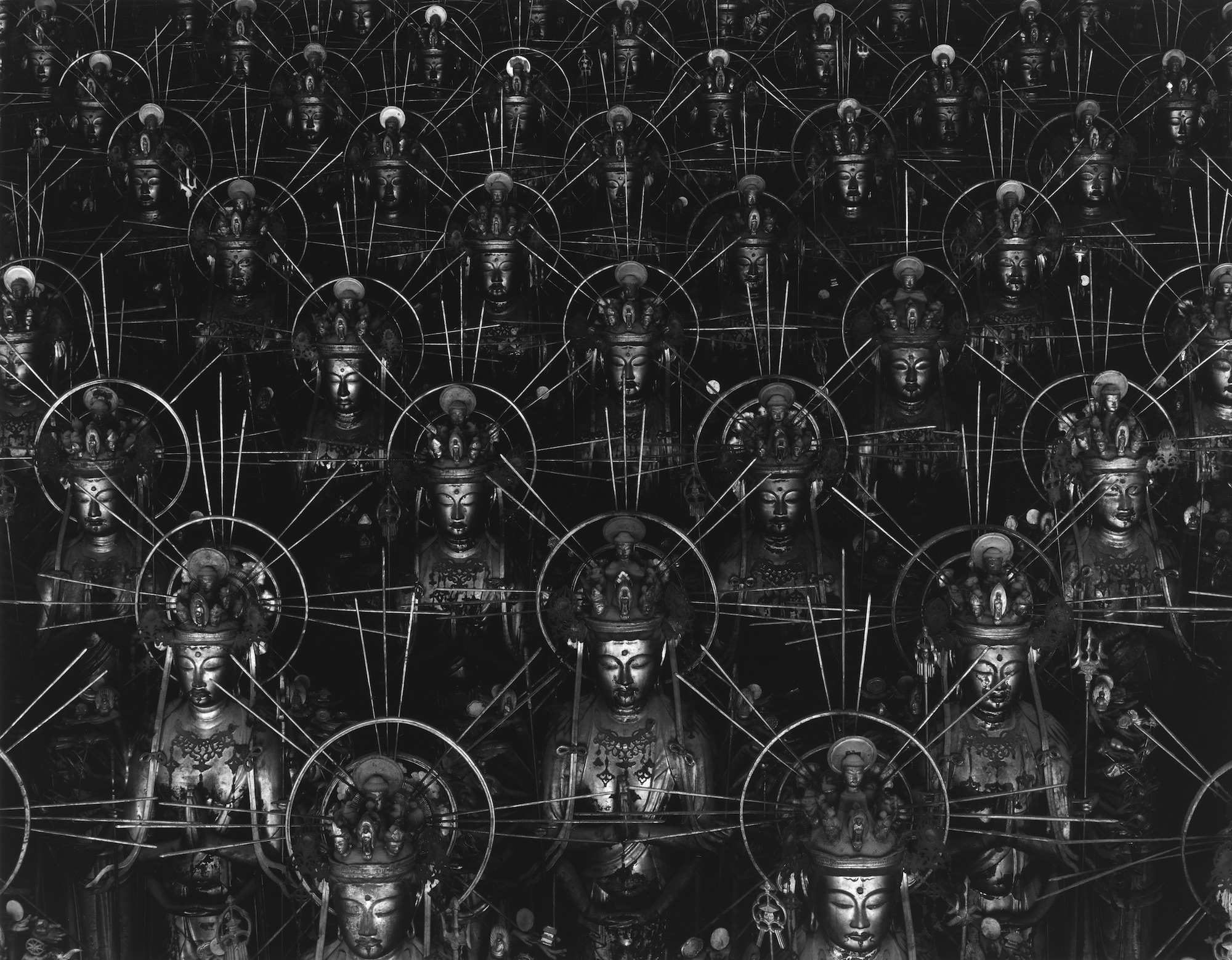

Renowned works by Sugimoto, such as the series Dioramas, Architectural Series, Conceptual Forms, The Images of the Sea, Sea of Buddhas, The Gates of the Paradise, Theaters and Seascapes have been showcased and sold worldwide. In two consecutive years, 2016 and 2017, the artist spent some time in Italy working on the ongoing series Theaters, shooting images of empty movie theatres using a bespoke 8×10 old-fashioned large-format camera operated manually.

“I am probably the only person who retains the traditional techniques needed to operate this camera, and I want to continue to achieve this quality,” he says. Sugimoto thinks that working with traditional photography instead of digital media makes a better picture if the photographer masters the handling of fresh film. Photography as a medium has been subjected to unparalleled technological advancement in recent years, but Sugimoto has no plans to stop working with his custom-made, old-fashioned camera. “I know all the tricks of operating this traditional camera and the quality of the final print is far superior to the outcome someone could obtain with digital photography. I spend a lot of time in the darkroom mastering the art of developing images and personally checking the quality of each piece, from the first stage of developing to the last step of printing and framing.” It was during recent travels around Italy that he proved he can still handle the challenging demand of using traditional photography methods. With a difficult-to-obtain permission to shoot inside the Pantheon in Rome for three consecutive nights, from dusk after public opening times until early morning before the site reopened to the public, Sugimoto worked non-stop round the clock to take long-exposure images of the Pantheon at night, developing them in the hotel room during the day to ensure every shot was as good as it could possibly be. “While shooting in the Pantheon at night, I developed pictures with a tray and portable equipment in my hotel room during the day. It was exciting and exhausting at the same time, but I needed to make sure I had the right images before the shooting permission ended. It was critical that the negative of each picture was just as I envisaged it.”

- Left: Ohio Theatre, Ohio, 1980; Right: U.A Walker NY, 1978

The photographs of the Pantheon are part of the series The Gates of Paradise, whose name is inspired by a discovery made by the artist during one of his visits to Italy. Sugimoto was shown the relatively unknown fresco entitled I Quattro Ragazzi, on the ceiling of the Teatro Olimpicoin Vicenza, the latest Palladian building in the north east of Italy near Venice. The fresco tells the story of four Japanese boys who converted to Christianity and toured around Europe visiting the leading spiritual places of the faith—Rome was the final stop.

Sugimoto already knew about the story, and the rediscovery inspired him to retrace their itinerary, which led him to shoot images of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, known as the Duomo, and the Gates of Paradise, known as Porta del Paradiso, the east gate of the Baptistery of St John, both in Florence, as well as the Pantheon in Rome. This story epitomizes the theme of exchange across different cultures, which is a running theme in Sugimoto’s work and life. “I was born in Tokyo where I was educated at a Christian school. Then I studied Marxism, economics and German idealism in Japan. It was only when I moved to the United States that I discovered Zen and eastern philosophy.”

The project and development of the Enoura Observatory is intended as a celebration of Japanese culture. The site comprises a display of ancient stones that Sugimoto eagerly collects and studies. They are displayed in triangles and circles across several areas of the space. “The stones are laid using an ancient Japanese technique. The work is so extensive that I have a team of dedicated craftsman who pose stones specifically for me. The site is unfinished. We plan to extend and develop it as far as the land stretches to the sea,” he explains. The Enoura Observatory is surrounded by nature and it dominates the bay, but “as with my work, where I make nature look even more natural, I modify and reinterpret it. In Enoura Observatory, the aim is to fulfil expectations about nature which are intrinsic to the Japanese culture. You cut trees, you remove grass and lay gravel instead. It is not wild nature we are recreating, but a space that reflects grace and embodies tradition.”

The view of the sea is of exceptional beauty and offers a new perspective on Sugimoto’s art, which encompasses art in a wider sense, including land art, space design and performance art, complementing his iconic photographic artworks that are displayed in the Summer Solstice Light-Worship 100-Meter Gallery, a fifty metre glass corridor that ends with a breathtaking view of the sea.

- Left: The Enoura Observatory by Franco Zanetti; Right: Hiroshi Sugimoto Portrait by Franco Zanetti

“After I established myself as an artist and had exhibited my works widely, I developed an interest in architecture. I am a sort of autodidact architect. That is how my knowledge of architecture evolved, learning by myself. I do not have a formal architectural education. I make architectural drawings and my associates endorse my ideas using the CAD system, and they ensure the construction is sound.” In 2008 Sugimoto founded the architecture design office New Material Research Laboratory in Tokyo, and through it he designs buildings, ranging from tea houses to shrines.

Sugimoto rejects the idea of retirement any time soon. “Inspiration is continuously coming to me, I believe there is no retirement age for artists. In my case, I want to renew myself year after year, and I want to avoid repetition, apart from my defining series Seascapes and Theaters. I continuously have new ideas coming to my mind. I am ageing, but I have new assistants who help me in fulfilling new challenging projects,” he jokes. “Some artists entirely delegate the manufacture of their works. Instead I produce artworks by myself to control quality and achieve the ultimate result. An artist who allows sufficient time for completion of each art work achieves perfection in every one. Even for architecture, I meticulously hand draw and then inspect each stage of design and production. I am very old fashioned.” If being old fashioned is part of his personality, it is also a way to avoid the pressure of the contemporary art market, which requires artists to produce a constant stream of new works for the satisfaction of a hefty and ever-growing demand.

“Inspiration is continuously coming to me, I believe there is no retirement age for artists… I continuously have new ideas coming to my mind”

In recent years and certainly since the beginning of his Odawara Foundation, the artist has been spending an increasing amount of time in Japan where he personally oversees the development of the Enoura Observatory. “After spending several years in New York I realized my inner self still remains deeply Japanese,” he tells me. “I am not American in any way. I just happened to spend many years living there and time passed very quickly.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 36

BUY ISSUE 36