When I was a teenager, during long weekday evenings at a playground near our secondary school, my friend Sammy would take a lighter and burn ‘smileys’ into her arm. The skin would pucker and bristle under the heat, forming a bulbous mound of skin, the colour of the inside of a watermelon. I would sometimes hold her wrist and turn it over, inspecting the damage, telling her it barely looked like a smile. I don’t think she intended to cause herself harm in any deep psychological sense; in fact, she didn’t ever seem to wince as she torched her flesh with the lighter. I would pull out my water bottle and squeeze the liquid over it.

Sammy felt no shame as our friends would jeer and encourage her. She used to look at me after, beaming. To make a mark can be thrilling, she seemed to suggest. Jackass’s Johnny Knoxville had an unyielding influence on a lot of the people I knew during my teenage years, a man who becomes a leitmotif of the individualist, post-millennium, self-injurious stuntman throughout Phillipa Snow’s Which As You Know Means Violence. Snow describes the book as a “pervert’s guide, examining the possibility of pain as an effective vehicle for profundity, liberation, feminism, subversion, eroticism, humour and divinity every bit as interesting as pleasure.”

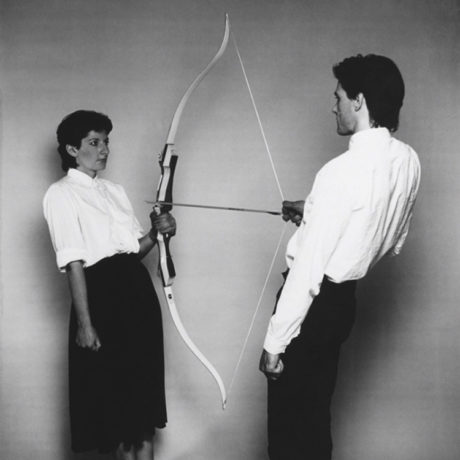

However, while Knoxville and his troupe of Jackass players were keen to distant themselves from ‘pretentious’ performance artists, for Snow it became “harder to tell the difference between what Johnny Knoxville et al, did and what, for instance, Chris Burden had done in 1971 when he enlisted an anonymous friend to shoot him in the arm”.

Snow’s ability to move from niche performance art to the messianic iconography of millennial Americana is one of the book’s greatest strengths. Indeed, through unlikely commonalities, Snow draws together performance artists such as Chris Burden, Nina Arsenault and Bob Flanagan with Buster Keaton and Johnny Knoxville.

While Burden’s performances commented on the brutality of the Vietnam war, Snow suggests that the two are not altogether dissimilar. Wasn’t Jackass a commentary on a post 9/11 masculinity? Snow characterises the show’s purpose as exploring “what it means to be a young man in America beset by the psychic indignities of economic downturn, terrorism, unemployment, hopelessness about one’s place in an increasingly dysfunctional society, and distant, quietly raging war”.

For artists such as Burden, Marina Abramović, or even Knoxville, Snow suggests that “it takes youth” to conduct death-defying acts like getting shot in the arm or carving a pentagram into one’s stomach (as Abramović did in Lips of Thomas). Like my friend Sammy, Snow suggests that artists prone to self-injury are “motivated by a kind of restlessness”, that they exalt an almost puerile thanatological drive, that “they do not so much announce themselves as carve their identities, bloodily and publicly into their skin, the way a teenager might carve his or her crush’s name into a school desk or a tree-trunk”.

How and why do people develop relationships with intense pain? There are many possible reasons, Snow says, which “tend to be one of more from a certain laundry list: trauma, Eros, infamy, national identity, parental influence, an interest in religious martyrdom, and war.” Most predominantly, however, Snow suggests that an artist’s tendency towards pain reveals the complicated nature of gender’s social conditioning, especially as it is projected on the body.

“Snow suggests that an artist’s tendency towards pain reveals the complicated nature of gender’s social conditioning”

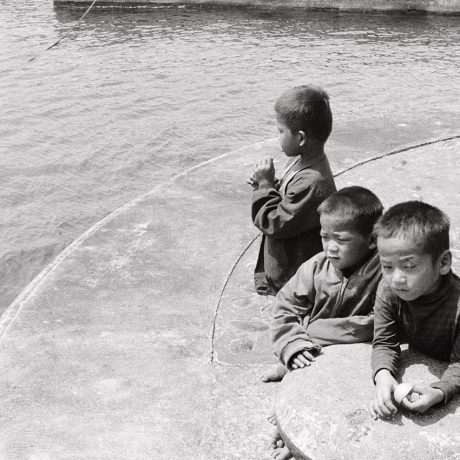

In a point that could have been further elaborated (and is underexplored in the history of performance and body art in general), this artistic tendency towards pain and self-injury also reveals the privileged contours of whiteness. Snow reflects that “most practitioners of this kind of art tend to be white. This is perhaps because Caucasian people do not have the same historical relationship with pain as other racial groups”.

Cis white women who make this kind of work, Marina Abramović or Gina Pane, for example, do so to exorcise “the feminine itself, a self-lacerating admission of the same terrible feeling of inherent victimhood”. That is, these artists make a spectacle of female suffering through pain.

By focusing on a larger corpus of artists, with a more concerted effort to focus on self-injurious and endurance-based body art from queer, and POC communities, Snow’s exploration of gendered embodiment might have put pressure on the idea that female subjectivity is some sort of internal truth emerging from the body.

In her brilliant reading of the viral YouTube video, British lads hit each other with chair, she writes that it “express[es] a truth about the use of injury and agony as a conduit for escaping, or at least gratuitously fucking with, the gender binary.” While Snow veers toward this territory of unpicking how gender operates in the history of the genre, there is another category of body artists absent in the book, those who don’t all necessarily ‘wound’ the body, but are invested in a politics of pain, endurance, and suffering that puts pressure on the gendering and racialisation of the body, (and the histories of violence which attend such processes). Tehching Hsieh, Ana Mendieta, Chitra Ganesh and Simone Leigh (known together as Girl), and Cassils all come to mind.

“What happens when these forms of self-injury intersect with other forms of self-harm, like exhaustion, hunger, confinement and endurance?”

In Which As You Know Means Violence, Snow figures most of the theoretical work of the book through the lens of physical wounding. But what happens when these forms of self-injury intersect with other, perhaps less obvious, forms of self-harm, like exhaustion, hunger, confinement and endurance? With a focus on the spectacularisation of self-injury, there is a critical tendency to only read this sort of performance or body art as extreme or excessive, or through the lens of annihilation or aberration.

Works like Chris Burden’s Shoot, which is often considered as an exemplary work of 1970s body art, are habitually thought about in terms of “mania”, “oblivion”, “agony”, “ecstasy”, “physical discomfort” and “inner turmoil”. Much of Snow’s criticism is focused on the excessive aftereffects of this genre, but I would argue that what undergirds so much of painful and self-injurious body art is the precarious balance between excess and mania on the one hand, and control and restraint on the other.

Crucial to all Snow’s artists is the use of pain as a conduit to authenticity, as a way to access the real. What feels striking is how staged and less-than-real these pursuits sometimes appear. Indeed, something that Snow only discusses towards the end of the book is what happens when things go wrong (she explores the tragic death of Pedro Ruiz at length). The ways in which the lure of pain, in its proclivity for accident, offers an epistemological break from what is knowable.

Though the works in Which as You Know Means Violence produce entertaining or spectacular forms of injury, scarification, blood, and pain, much of this kind of art is also about carefully controlling the execution of a plan, or about training and restraining the body in judiciously managed ways. Perhaps the rub, then, is that while it is a very human impulse to desire death-defying mastery over the self, what these works tend to always reveal is that despite our best efforts, we are complexly vulnerable to a world, and others, that we cannot always control.

is a London-based writer and academic

Which as You Know Means Violence by Philippa Snow is out on 13 September (Repeater)