‘Not everything has to be precise—like life, unexpected things happen.’ DO HO SUH is well known for the meticulous precision of his sculptural works. But recent experiments and discoveries are drawing his practice in unforeseen, more chance-led new directions. ‘And, you know what, it’s fun,’ he tells GILLIAN DANIEL.

‘I really should stop giving interviews. I feel like everything has been asked and I just have nothing to say anymore,’ Do Ho Suh announces in a resigned tone as we settle down in his studio on a grey London morning. That’s not a promising opening statement for an interviewer. But my nervousness is quickly dispelled over what ends up being a two-hour conversation about chance, discovery and speculation. These three ideas are not what immediately come to mind when thinking about Suh’s best-known work—meticulous replicas of his previous homes.

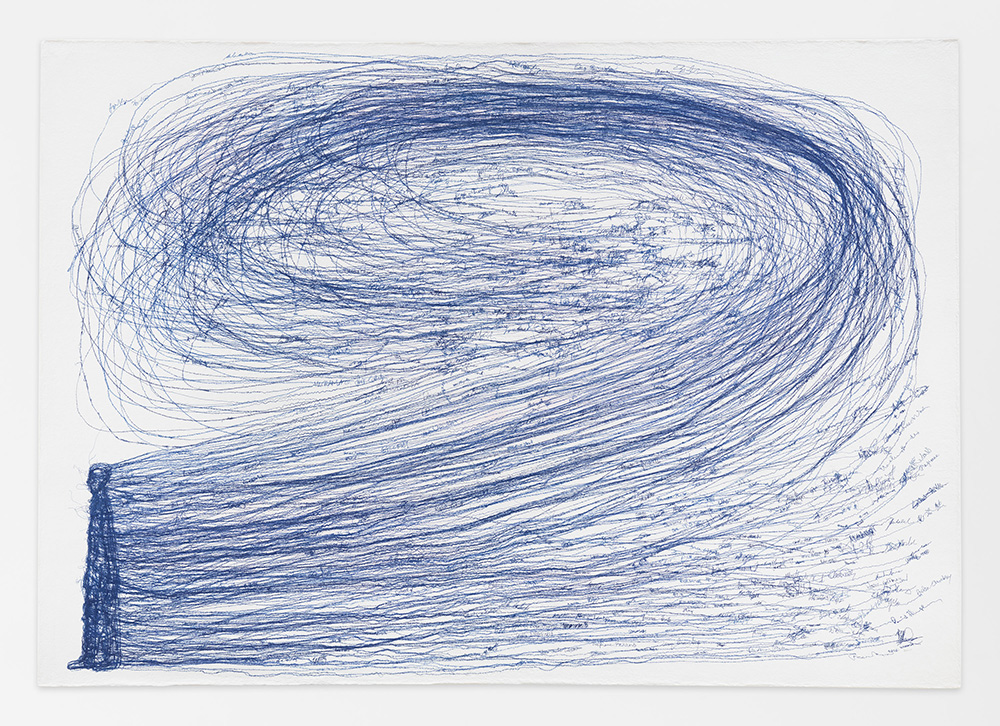

Suh busies himself by taking out hundreds of bits of colourful embroidery from a bag and laying them out on the table. ‘Maybe we can talk about the thread drawings for a change. I’m getting a little tired of talking about my fabric architecture,’ he says. The technique Suh uses in his fine thread drawings was developed during his first residency in 2010 at the Singapore Tyler Print Institute, a creative space for conceptual developments in print and paper. The first two weeks of his three-week stint were a struggle. ‘Printmaking and papermaking were not my speciality. But STPI allows artists to explore techniques and medium in paper and printmaking that are vastly different to their practice. I was stuck at first, though. I only made drawings on my sketchbooks. Then they suggested: why don’t I play with thread?

‘It’s funny. I never came across the idea of using thread even though I use thread all the time in my fabric pieces. But I gave it a shot. I started to make drawings out of thread on wet paper. But the loose thread was hard to control. So we came up with the idea of sewing on thin tissue paper and trying to dissolve the bits of paper around the drawings and transferring that onto thicker paper.’

Many of these early experiments failed as tissue paper proved a difficult medium. Suh struggled to fully dissolve the paper and transfer his small drawings to make larger-scale works. ‘It was actually one of the interns with a background in textiles who asked me, “Why didn’t you use gelatine paper?” That’s how I learned about this type of paper. Gelatine paper is actually used for embroidery and is designed to completely dissolve in water. When paper is being made, it is wet and spongy. When the gelatine paper touches it, it mostly dissolves and leaves only the bits with the thread behind. We then rub the drawings gently to transfer the threads and help the fibres bind into the paper fibres.’

Suh found this mode of working and the results it generated so fascinating that it left a lasting influence on his practice. He is currently gearing up to do his second residency at STPI, with an exhibition planned for November. ‘I like that there is an unexpectedness to the thread drawings that is so different from my other works. There are all these little accidents. Sometimes, when the tension between the two threads in the sewing machine is not right, little loops of excess thread appear at the back of the sewing. In the beginning, I trimmed these excess threads, but I grew to like how they change the shapes of my drawings when they interact with water in the paper pulp. Also, when the gelatine paper dissolves, my drawings often shrink a little bit and the lines go wiggly, so there’s lots of room for little accidents and chances.’

I express surprise at this, as extensive planning and precise control are central to so many of Suh’s architectural pieces. ‘When I developed this technique,’ he replies, ‘I didn’t know I would feel this kind of freedom. It’s a very different process from making my installations. My installations, especially the architectural pieces, take a very long time to plan and execute. Everything has to be exactly the way I want it, down to the last little detail. Here, on the other hand, it’s the opposite. I can plan it, but it doesn’t come out exactly how I want it. I think that there is a kind of beauty here that the artist cannot control everything and in the end you just have to play with it. One of the reasons I became a sculptor after being a painting major was because I was attracted to how it was a different way to make art. In painting, you cannot really explain every colour and brushstroke.

‘As a young man, I was frustrated by how the artist can never have full control over his own work. That’s why I became drawn to sculpture and architecture, where there are always rules, like the laws of gravity, that you have to work with. Everything has to be planned. I liked that aspect. I felt I was making something more real. Painting was too arbitrary. But now I realize that’s why painting is painting and sculpture is sculpture. Not everything has to be precise—like life, unexpected things happen. I still like making big things that involve rigorous planning, but I’ve discovered something different inside me, that actually I’ve been looking for some kind of excuse to enjoy the freedom of creativity. And I found that in the thread drawings. I like the different forces and energies I encounter making these works.’

Before moving to the US as a young man and embarking on his career as a sculptor and installation artist, Suh had planned to follow in the footsteps of his father, the influential South Korean painter Suh Se-Ok. ‘It’s funny how these things happen, how life works out. It really is coming full circle—I’m even thinking about painting again. It may take a while, as I still have many ideas I want to work out for installations, videos, sculptures and things like that. I don’t believe anything happens without a reason. I am sure that there were undercurrents of a different type of creative energy that I didn’t know about that the STPI residency helped me discover. And I’ve kept going.’

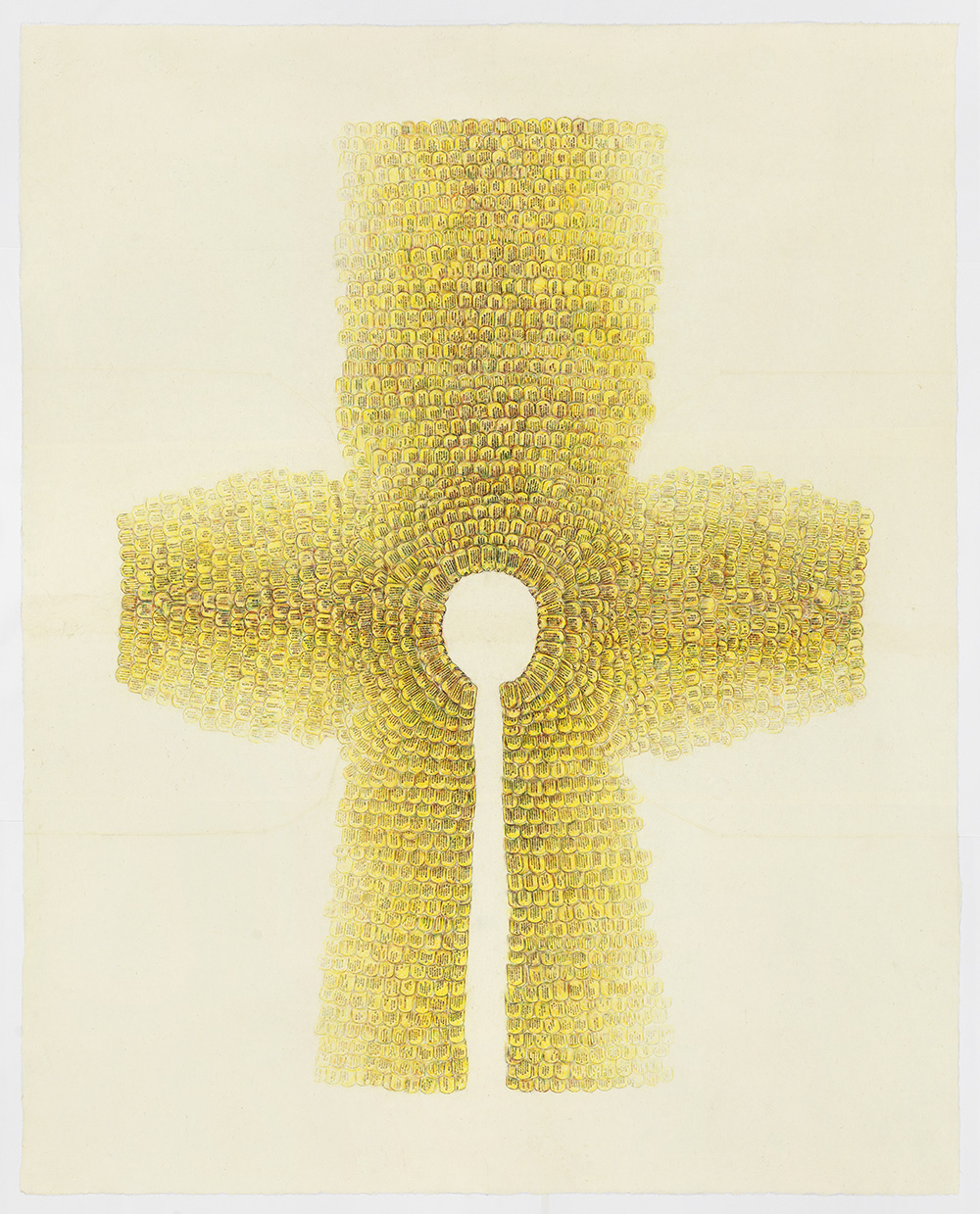

The concept of home never fails to come up in the interviews Suh has given. The artist’s itinerant life has indeed had a profound influence on his practice, with spatial and psychological migration a constant thread. I wonder if his rediscovery of works on paper represents a departure from this earlier thematic preoccupation. Suh mulls this over, then slowly replies, ‘My architectural pieces are exact replicas, 1:1 replicas of the actual house or building I was trying to reproduce. They are not abstract forms, but forms based concretely on reality. But drawings can be made of anything. I’ve wanted to make so many architectural pieces that just cannot be realized in the three-dimensional world because of the limitations of materials, space, gravity, financial resources—the list is endless. But all these thread drawings were based on sketches that I’d already made in the many sketchbooks I’ve had over the years. Drawing is the perfect tool for me to flesh out crazy ideas for crazy projects, which is what I like about it.’

Suh goes to a nearby shelf heaving with sketchbooks, ‘For example, this is one of my ideas for the perfect home, on an imaginary bridge between Korea and the US. My house would be right in the middle. This drawing was made in 1999. This is the type of sketch that appeared very often in my sketchbooks, for a project that is impossible to make and so never got seen. Now that I work more with drawings, I have started to show this type of work. It gives me a great sense of satisfaction, showing things that I thought initially were never meant to be seen.’ Suh slides a new book on his Bridge Project across the table. This project started with the exhibition A Perfect Home: The Bridge Project at Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York in late 2010.

‘The exhibition was essentially an elaborate proposal for a bridge, which I took great pleasure in. Of course, there is no bridge that connects Korea to the US because of all the different factors. But the point was that I enjoyed speculating about the possibilities. The project became real to me and it was really exciting, trying to make something tangible materialize. Before I started working more with drawing, it was difficult to realize these ideas. Rediscovering the two-dimensional medium has allowed for these new directions and new expressions of my previous conceptual concerns.’

There is a cathartic element in the vigorous body of preparatory drawings, animations and videos that Suh has produced for his Speculation Project. ‘I have been showing my fabric architecture for ten years and I think it still blows people’s minds because of the attention to detail. But you know I’m not actually crazy about the individual elements that make up those pieces, because they came with the building. The scale of the building is spectacular and the detail is rich, but that was just the conditions that came along with my previous homes—I did not choose these things. There were no interventions or accidents here. Because of that, and also because of the translucent quality of the material, I feel it is actually lacking in some way and becomes sterile quickly.

‘I started the Speculation Project a long time ago. These are the works I have made in between the familiar bodies of work that people have come to know. They’re an important part of my process that has become more and more important to me. There is also a whimsicality to these works; a lot of them are quite funny. There is a childishness to my speculations. I like that there are more points of entry. And, you know what, it’s fun.’

On the topic of fun, the Speculation Project has allowed Suh to rediscover a childhood fascination: toys and modelmaking. ‘It started with me looking for a model truck for Secret Garden. I went to a modelmaking store in Japan and that really reactivated my interest in modelmaking and toys, which I enjoyed as a child, just like every small boy, I think. It started as part of my work but then it became an obsession. I got completely hooked, and now I just keep buying and buying new kits even though I have no time to make them!’

So many of Suh’s earlier projects were about the act of looking back, achieved by trying relentlessly to re-create his previous homes. These recent projects suggest that he has started taking other phases of life in hand. Instead of the poignant retrospection that we have come to expect of Suh, he has started to take things in and weave his experiences into a wider narrative.

‘You’re right,’ he says emphatically, ‘That’s the direction I’ve been going in in my recent works. I now see life as a linear journey. I tend to think of life in terms of space. Your own movement through space is how you inhabit the physical world. I came to London five years ago and right away I got married and had two children. A lot of people used to ask me: Is this going to show in your work? I always responded that it was too soon. But now, I’ve finally started to think about my experiences of living in London.

‘My arrival in London coincided with the arrival of my daughter. We’re both new to London in a way and both discovering new environments together. This is a new element to my work. I’ve made a video-recording device that I can attach to her pram and I push the pram as my daughter and I go places together. Our route—for example, from here to the nursery— will be documented and that is how we will explore the neighbourhood together. I am excited about this and I hope I can show these works soon in London.’