Isn’t a holiday supposed to be a time of rest and recuperation? You wouldn’t think that in the west, where screams of “Spring Break!” permeate our vision of school holidays in the US and public holidays are often an opportunity to spend five hours too many in a bar or pub on a perfectly good and sunny day.

Rodnik, Russia. Photo by Dmitry Lookianov

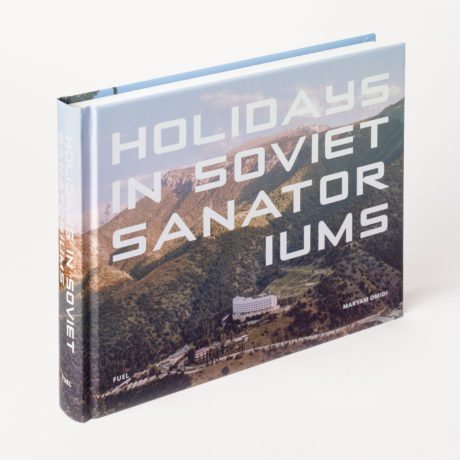

But in the Soviet Union, a break from work was a little more dignified. Holidays served the purpose of maintaining the fitness and health of a productive workforce, as Maryam Omidi reveals in her book Holidays in Soviet Sanatoriums. Omidi, who was previously features editor for the Calvert Journal, takes us on a trip around the USSR, in a survey of the sanatoriums that are still standing—since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, many of these havens of calm and health have fallen into dilapidation and exist only as ruins. Some, however, remain. Some are even still state-owned, whilst others, such as the sanatorium in Lipki, Russia, have attempted to modernize and attract younger visitors with new treatments like chocolate body wraps.

- White Nights, Sochi, Russia. Photo by Egor Rogalev.

- Reshma, Russia. Photo by Dmitry Lookianov

“A cross between medical institution and spa”, sanatoriums rose to prominence after Joseph Stalin’s 1936 constitution announced a “right to rest” for all Soviet citizens. In the early twentieth century, this meant highly regulated and controlled holidays which could be paid for, in part, with “putevki”, state-issued vouchers which, in theory, were prioritized for industrial workers and those with medical conditions. Sanatoriums are some of the most ambitious and utopian examples of Soviet architecture, which shifts from constructivism in the 1920s to Stalin’s neo-classicist empire style and back to modernism from the 1950s onwards—all architecture that has become trendy in the nostalgic west, similar to the way brutalist blocks like the Barbican and Alexandra Road estate in London have become regular backdrops for fashion photoshoots. Fuel, the book’s publishers, are also responsible for photographer Christopher Herwig’s 2015 book Soviet Bus Stops, as well as its second volume last September, and a whole host of other Soviet-themed publications.

Salt Mine, Belarus. Photo by Egor Rogalev

As sanatoriums were taking off in the early twentieth century, the rise of “kurortology” in the USSR—a study of the medical effects of nature and the elements on humans—led to many Soviet kurortologists advocating reconnection with nature and the landscape as a way of healing illness and easing social alienation. It’s no surprise, then, that many sanatoriums are situated in sublime landscapes; lush, densely forested countryside, rocky mountains and fairytale lakes are the backdrop for the often stunning photography (by a host of photographers) which illustrates Omidi’s travels. Some of the most arresting images, however, are Egor Rogalev’s photographs of the National Speleotherapy Clinic in Belarus, which is located entirely underground. This sanatorium is also a working salt mine, offering health benefits to individuals suffering skin and respiratory problems, who spend their time relaxing and exercising whilst breathing in the salutary air.

- Matsesta, Sochi, Mineral Water Bath. Photo by Dmitry Lookianov

- Tskaltubo, Georgia. Photo by Claudine Doury

Omidi describes visiting a Soviet-era sanatorium as “like stepping back in time”, yet the treatments available at these establishments may seem space-age to those used to going to Cowshed for a massage. She guides us through the crude oil baths of Azerbaijan’s Naftalan, the paraffin wax masks and UV light-emitting sterilization lamps of Kyrgyzstan’s Aurora and the sweet foamy oxygen cocktails available at Bucuria-Sind in Moldova. As someone who has never been to any form of spa, I know now that I will settle for nothing less than lying back and being slid into a hyperbaric oxygen therapy chamber.