Would art exist at all without appropriation? In ancient times, the Romans copied the Greeks. During the Renaissance, subject matters and styles were replicated from panel to panel. The 20th century saw Pop artists take their cue from mass media and advertising. And then there’s the practice of transforming found objects into art: think Marcel Duchamp’s signed urinal and Tracey Emin’s stained and crumpled bed.

Sometimes you have to look back in order to move forward. Today several young artists are dipping into old art forms both to situate themselves within the canon and to start new conversations.

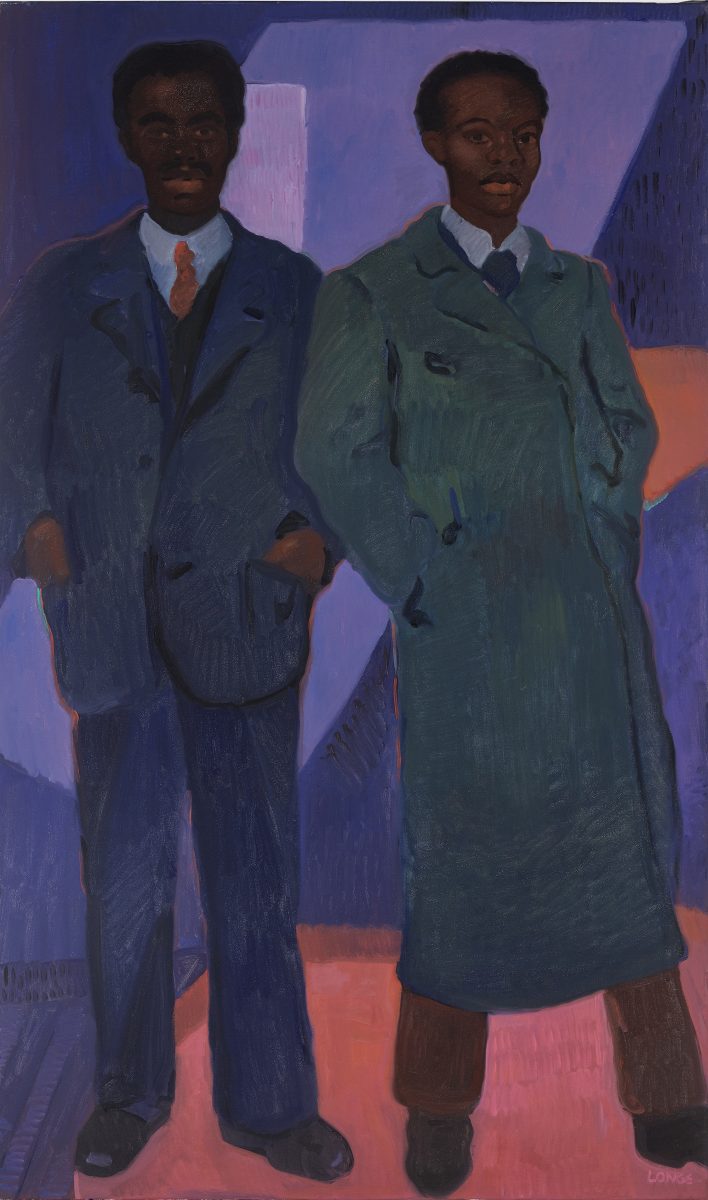

Sahara Longe trained at Charles H Cecil Studios in Florence, an atelier that adheres to the Renaissance tradition of progressing from cast and figure drawings to portraits painted from life. She studied the palettes of Old Masters such as Anthony van Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens and made copies of their works. “To use these techniques and colours that have been forgotten by time is a little like using a lost language,” says the British artist. “It creates a strange connection between you and the past.”

For Longe, who was born in 1994, it’s a way of honouring the qualities that she admires in existing pieces of art history while also developing her own practice. Her approach is reminiscent of the Old Masters, for whom, she says, “Nothing was random, everything was very carefully laid out and planned.”

“Sometimes you have to look back in order to move forward. Today several young artists are dipping into old art forms”

She appreciates their compositional strength and anatomical understanding. Longe, too, uses ‘little tricks’ to nudge the viewer’s eye around the canvas and encourage a certain reading of the narrative. Lately, when it comes to colour, she’s been looking to Edvard Munch and the German modernists, whom she respects for their ability to break down imagery without diluting a story’s essence.

But Longe’s vivid portraits, which flirt with abstraction and appear to gently pulse and glow, are entirely her own. She paints Black figures (family and friends) who she says wouldn’t have appeared in the Old Masters as subjects in their own right. “They wouldn’t have appeared in Modernist paintings either, except in a sort of self-consciously exotic way,” she adds. “They’re wholly contemporary, stories of our time.”

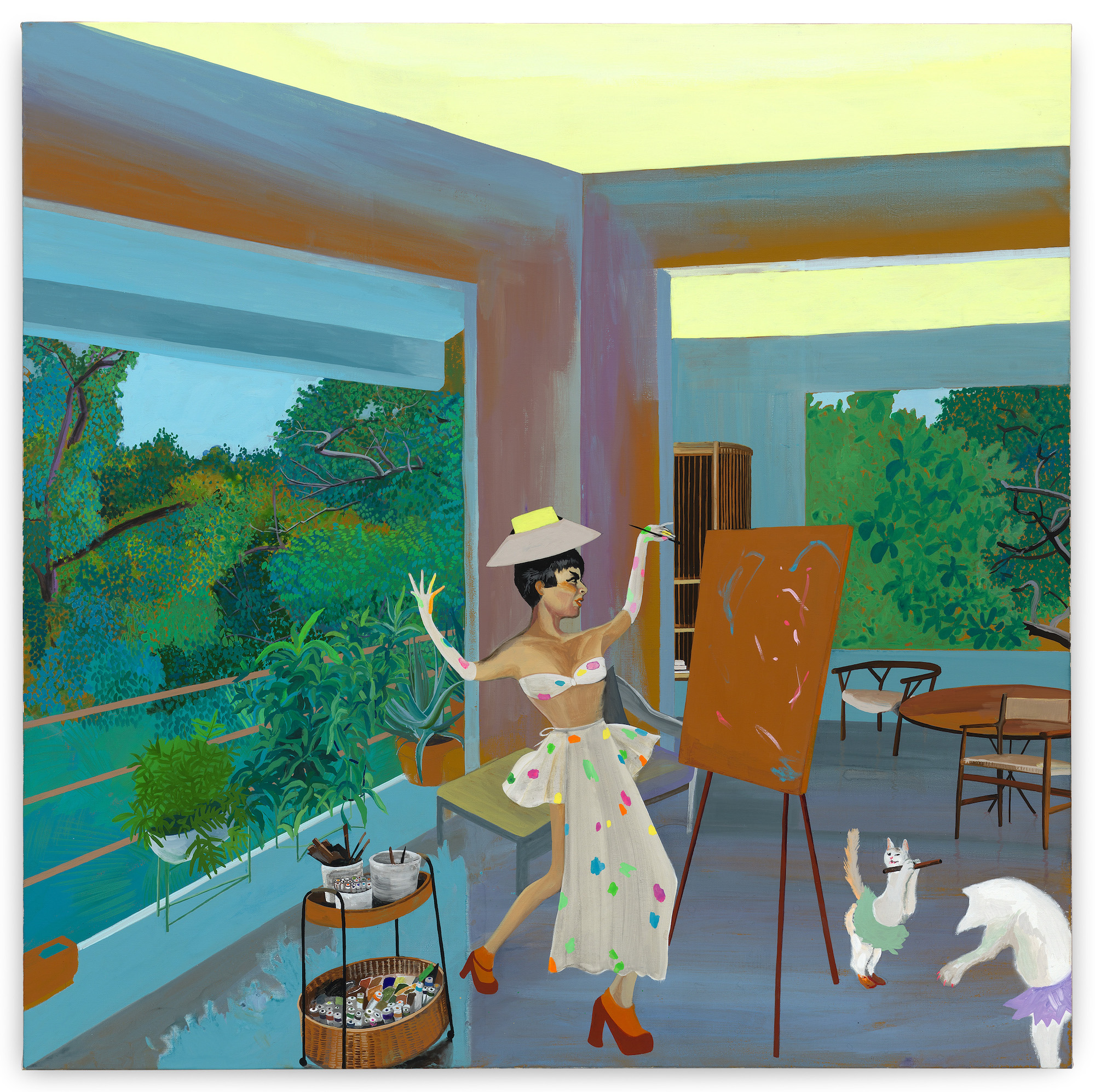

For Flora Yukhnovich, part of the appeal of the Rococo, that 18th-century movement associated with indulgence and ornamentation, is that it feels contemporary. “In a way, I think we’re living in another Rococo period,” says the London-based artist. “The internet and all its tendrils feel Rococo: the way we use images and the theatricality of image-making, the emphasis on consumerism and aspiration.” She finds connections between 21st-century visual culture and the flamboyant paintings of François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, reimagining aspects of their works to explore themes such as desire and the female form.

While she doesn’t regard her works as revisionist, Yukhnovich does find herself critiquing and celebrating certain artists. Take Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. “There’s a complete lack of angst about him and his work, which for some reason we’ve come to think of as an important part of being an artist and a genius,” she says. “His subject matter is slippery, which I like because it means you can come back to it fresh each time. Some people consider it shallow. It’s a shame because I think he’s the best colourist who’s ever lived.”

At times, Yukhnovich’s tantalising abstractions (which comprise pastel greens and blues, lemon yellows, sweet violets, and bodily pinks) stem from a single point of reference. She starts out trying to understand everything she can about a painting and the lexicon of a particular artist. “I’m thirsty to bring together a whole load of material and to find my own language within that,” she says.

With her most recent series, which draws upon a medley of images of the Roman goddess Venus, she printed out pages related to art history, mythology, and popular culture. “I stuck everything on the wall, and reduced it, and reduced it, and I was left with a kind of connective tissue,” she says. “There was a feeling I got from seeing it all together, and I wanted to capture that feeling, to make it solid.”

- Left: Flora Yukhnovich, Bombshell, 2021; Right: Crème de la Mer, 2022. © Flora Yukhnovich. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

The Dominican artist Hulda Guzmán (whose technicolour paintings exist in a space somewhere in between the human, natural, and mythological worlds) also seeks to capture a feeling in her art. “To me, an artist is someone who attempts to express the unfathomable, that which cannot be defined,” she says.

“Your new values and new perspectives will ever so slightly modify the way people look at the old order, the things we took for granted”

Guzmán’s cast of characters (children, animals, fantastical creatures) populate modernist interiors and lush landscapes that echo the paradisical scenes of Paul Gauguin and Henri Rousseau. She draws on surrealism, Mexican moralism, and Caribbean folk traditions to probe postcolonial and ecological discourse. By bringing together the everyday and the allegorical, she hopes to shine a light on multiple ways of being. “I intend to bring attention to the different dimensions of existence that conform our human lives, and which remain ‘unseen’,” she adds. “Who’s to say which perspective is better or more morally justified than another?”

Guzmán isn’t interested in marrying traditional references and techniques with contemporary subjects. Instead, the subjects that capture her imagination (human nature and our relationship with the natural environment) are timeless. Her works celebrate nature in its infinite variety and are painted from life on her native island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean. “I don’t feel comfortable making up information regarding nature, or even relying on my memories of what wilderness looks like, because nature is such an incredible designer,” she says. “I feel like an instrument of nature. It’s a humbling experience.”

“To use these techniques and colours that have been forgotten by time is a little like using a lost language”

Yukhnovich says something similar with regards to quoting from art history. She would go as far as to say that, without it, she wouldn’t be able to paint and have it make any sense. “I’m painting out of curiosity,” she explains. “I’m trying to make and hold and see these things that I can’t quite articulate.” As for why so many artists today are finding inspiration in old art forms, perhaps, she says, it’s simply that they’re allowed to, they’ve been given permission to by those who borrowed before.

For Longe, it’s a balancing act. “You’re trying to add your own work of art to this existing canon, and your new values and new perspectives will ever so slightly modify the way people look at the old order, the things we took for granted,” she says. “And yet, you hope that there’s continuity, that the new work can stand up to look the old works in the face and maintain its own presence; otherwise it isn’t really art.”

It’s about absorbing and adapting, learning and unlearning. As Longe says: “You have to know the past, in order to create the present.”

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April