The figures that twist and fragment in the paintings of Magnus Plessen seem to possess both mechanical and deeply human qualities; a curious match of fleshy limbs and synthetic form. The body is cut, taken apart and re-stitched, as if each part belonged to a child’s puppet.

Plessen’s research in recent years has focused on the horrors of World War One, exploring the physical traumas and the long-term psychological wounds inflicted. The introduction of automatic weapons brought with it a new ferocity of violence and injury, whereby hundreds could be wounded with little more than a trigger-pull from a distance. The pioneering work of doctors at the time in their attempts to reconstruct the broken and maimed body, particularly in assisting soldiers with facial injuries, paved the way for modern-day plastic surgery.

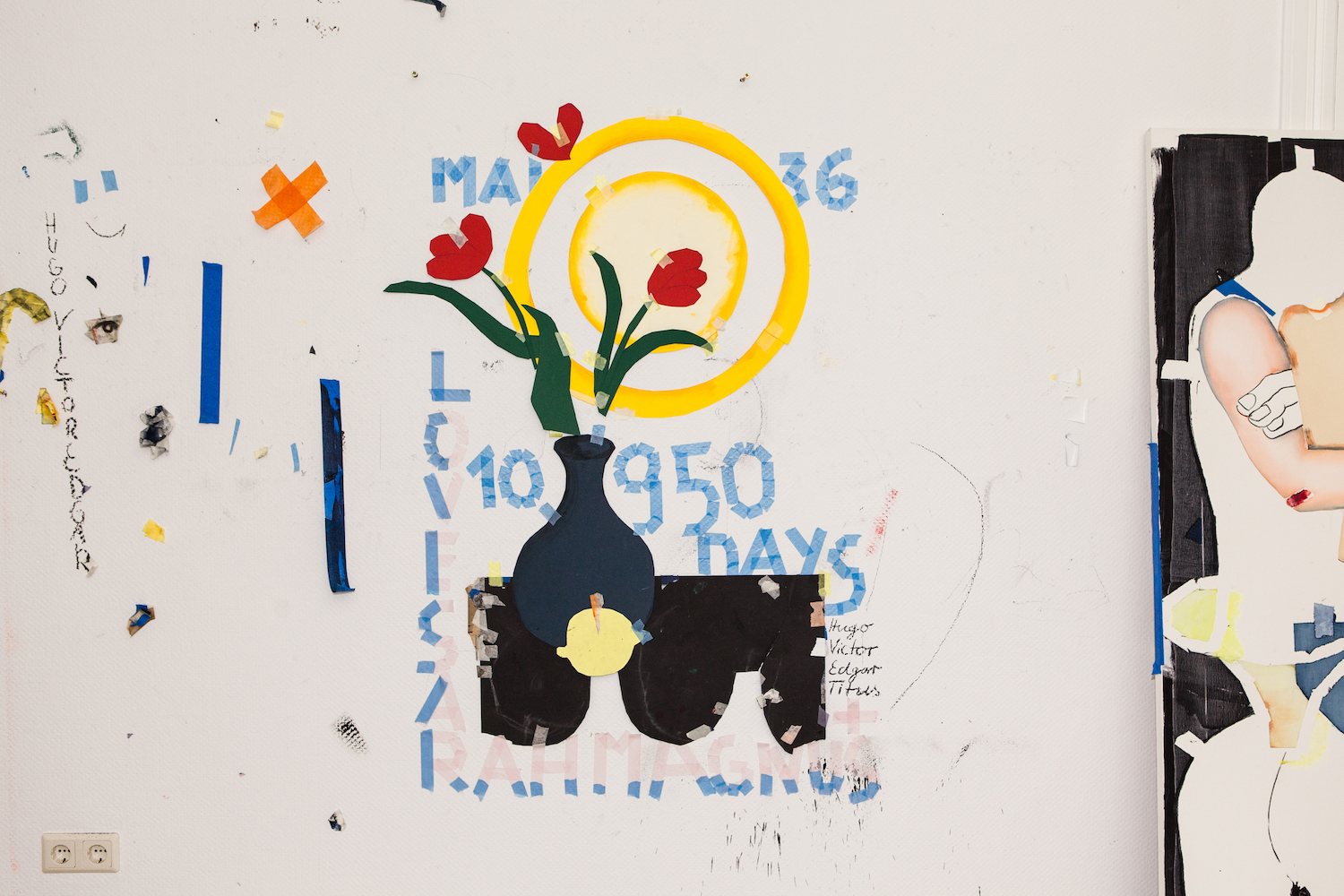

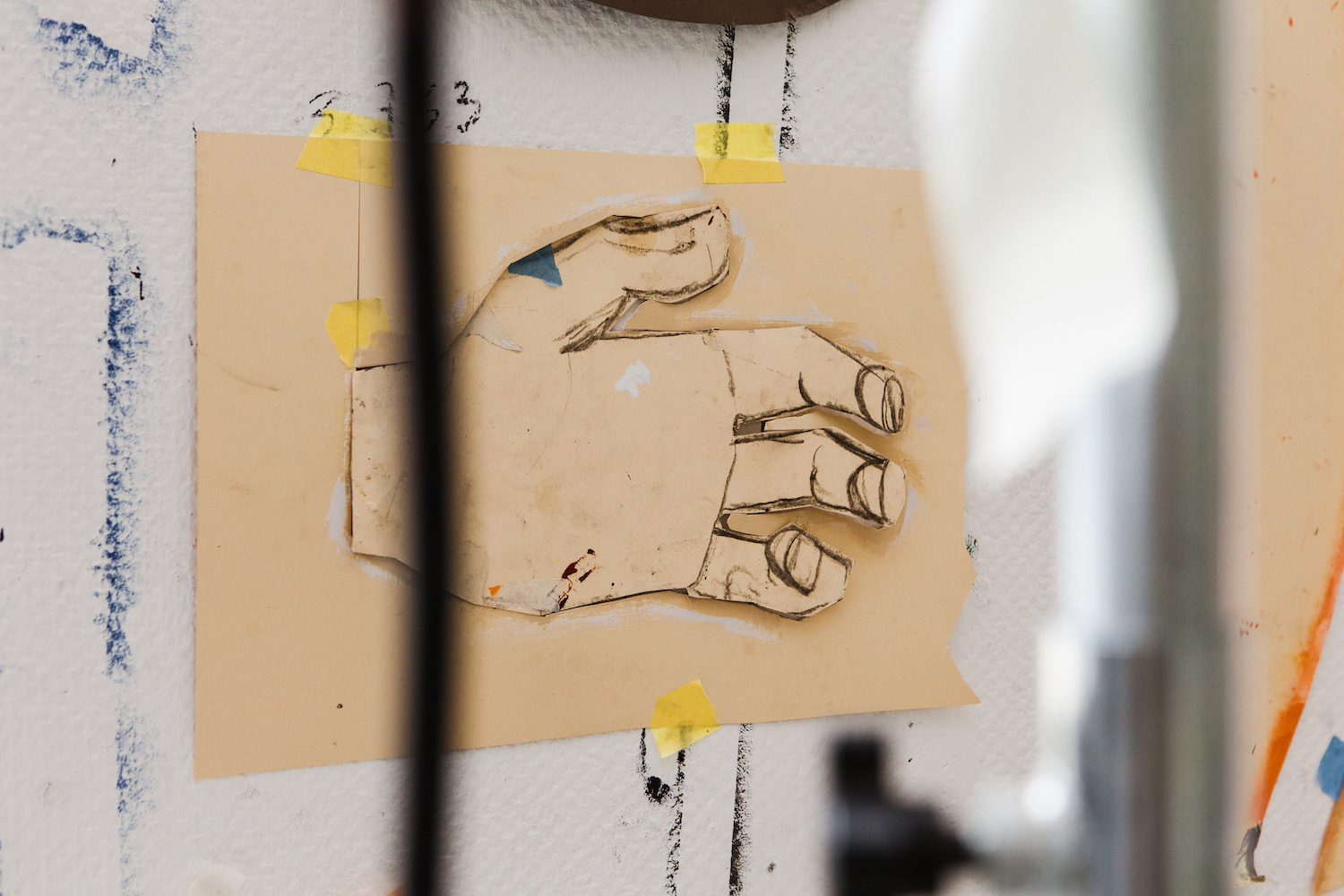

Plessen works frequently with stencils, using these cutouts as a starting point for his paintings. Arms, legs and ghostly faces appear and disappear, gathered in layers that highlight the spaces between them. These are bodies that have been broken but built up once more—restored but never fully repaired.

How long have you lived and worked in Berlin?

I moved to Berlin thirty years ago.

What is most important to you in a studio, and why?

I have worked in different studios all over Berlin. Different in terms of architecture, historical context, feeling and physical location on the city map. I was able to move to areas in the eastern part of town, for instance, which were invisible to the radar of the art scene at that point. I had a studio in a former Aga Film building next to the Strafvollzugsanstalt Rummelsburg. To walk past the old prison wall along areas of industrial waste was very inspiring. Today, the wall is gone and the prison has been converted into a housing project. I believe this is a fantastic characteristic of Berlin: because of its historic situation, I was able to continuously discover places which had not been used as studios before.

I worked on top of a corn silo in Moabit in a space which, cathedral-like, opened up in the middle to a ceiling height of about eight meters. Instead of an altar, though, there was a huge machine in the middle of the space: a corn mill which reminded me of Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936). I also worked in a hangar on the former Royal Air Force Station in Gatow, which today houses part of the Military History Museum. The original airport was built by the Nazis in 1936. I worked alongside soldiers in uniform who were restoring historical aircrafts.

Today my wife and I and our four sons live and work in a manor house which was built in 1914 in Dahlem. It is a great place which stands with one leg in the nineteenth century and the other in the twentieth century.

“I have worked in different studios all over Berlin. Different in terms of architecture, historical context, feeling and physical location on the city map”

Do you paint from photographs? How does history shape your work?

I purely work from my imagination. I have, however, researched extensively on the hardship soldiers went through in World War One trenches. The body of paintings which I have been working on over the last four years (over fifty paintings by now) is informed by what I found out. I will continue to work on my 1914 series until 11 Nov 11 2018, the date the war ended a hundred years ago. I will be closing this project with a show at Konrad Fischer Galerie in Düsseldorf.

Your paintings take on an almost sculptural quality with their many layers. Could you describe your process of building these up?

The first portraits of the series, which I did in 2014, focused on soldiers with facial injuries. These were injuries inflicted by a new generation of weapons, which exposed the soldiers to an unknown experience of physical and psychological violence. A team of doctors and artists tried to rebuild lost facial parts, sometimes using techniques common in sculpture making. This is the beginning of plastic surgery as we know it today. The figures in my paintings are built from individual body fragments, which I pre-fabricate as stencils in my studio. Hands, legs, feet, heads and so on. The process does feel more like assembling a sculpture than painting an image.

You are largely self-taught. What were some of the biggest influences for you when developing your practice?

Manuals of sculpture- and photography-making, and technical manuals which are about how to make a sculpture and image. Particularly in sculpting, I am intrigued by methods which involve the touching of reality—like taking a cast. Even though painting is praised for its visual qualities, I have developed methods of blind representation.

“The figures in my paintings are built from individual body fragments, which I pre-fabricate as stencils in my studio”

You have been working lately with stencils. What led to this, and how do you utilize them in your paintings? how has this shaped your work?.

I am quoting from a very moving song by Reinhard Mey’s It’s About Time:

“I hope it was a clean shot that hit you.

Or was it a bullet that shattered your limbs?

Did you call out for your mother until the end,

did you run away on your leg stumps?

And your grave, does it hold more than a leg, a hand?”

World War One created a previously unknown need for prosthetics of all kinds. Legs, hands, arms, noses, chins, eyes… My idea of mankind has changed finding out about what happened to soldiers in the war.

The elusive figures depicted in your paintings suggest everything from folk art to surreal marionettes. What is your relationship to them?

Looking at Untitled 45 (2018), I feel that the three heads could exchange places. The female head could move up to the position of the skull, and the skull to the position of the face wearing a mask. This movement feels mechanical, as if involuntarily provoked by an inbuilt mechanism. At first this doesn’t feel human. Looking at the puppet-like figures, however, I am intrigued by their ability to involve the viewer emotionally and intellectually. This exchangeability of given body relations—female head on female body, male head on male body, skull and skeleton—moves me very much.

In the many field reports I have read, soldiers tend to talk about losing their ability to distinguish between living and dead comrades. The way these soldiers talk about this sensation feels emotionally detached. Robert Graves writes in his autobiographical book, Goodbye to All That, of how the human faculty which registers emotions shuts down after the first combat.

Do you keep regular hours at your studio?

If things go well… I keep regular hours from eight in the morning until four in the afternoon.

With the rise of digital culture, there has been much discussion around the possible imminent death of painting, as well as much enthusiasm for its continued success. What is your take on this? What appeals to you about painting?

I feel that by accepting a set of given limitations that come with working in the traditional medium of oil on canvas, I have discovered my own way of representing the world as I perceive, think and feel about it. I believe that this is probably even more so than if I had based my practice on technical novelty.

Photography © Kristin Krause