Writer Eloise Hendy explores the incredible work that Hospital Rooms are doing inside, and for, hospitals in the UK.

Around ten years ago, a close friend of Niamh White and Tim Shaw was admitted to a mental health unit after being sectioned. When the pair visited her, they were struck by just how inhospitable the hospital was; how devoid of colour and comfort. They couldn’t shake the feeling that the harshly lit, austere corridors must be unbearable for someone experiencing serious mental illness and distress, like their friend. “The shock of visiting them in that stark, cold ward made us want to see if we could do something to improve spaces in mental health wards,” White and Shaw tell me. Having worked in the arts for ten years each – White as a curator and Shaw as an artist – they believed they had the skills and the community connections to be able to transform hospital environments with contemporary art, making them less dingy and clinical for the patients and staff residing there. They also believed that these transformations would be more than aesthetic facelifts, but could play an active role in the recovery process, providing solace, inspiration and dignity for people during their most vulnerable moments.

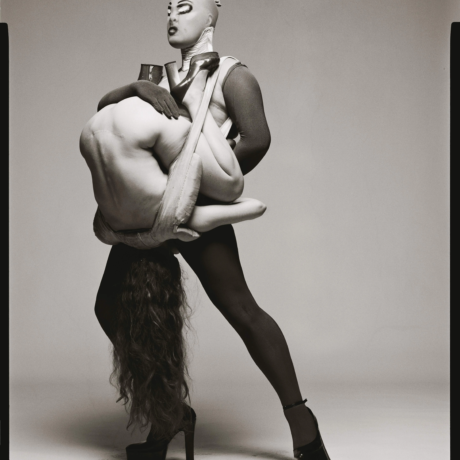

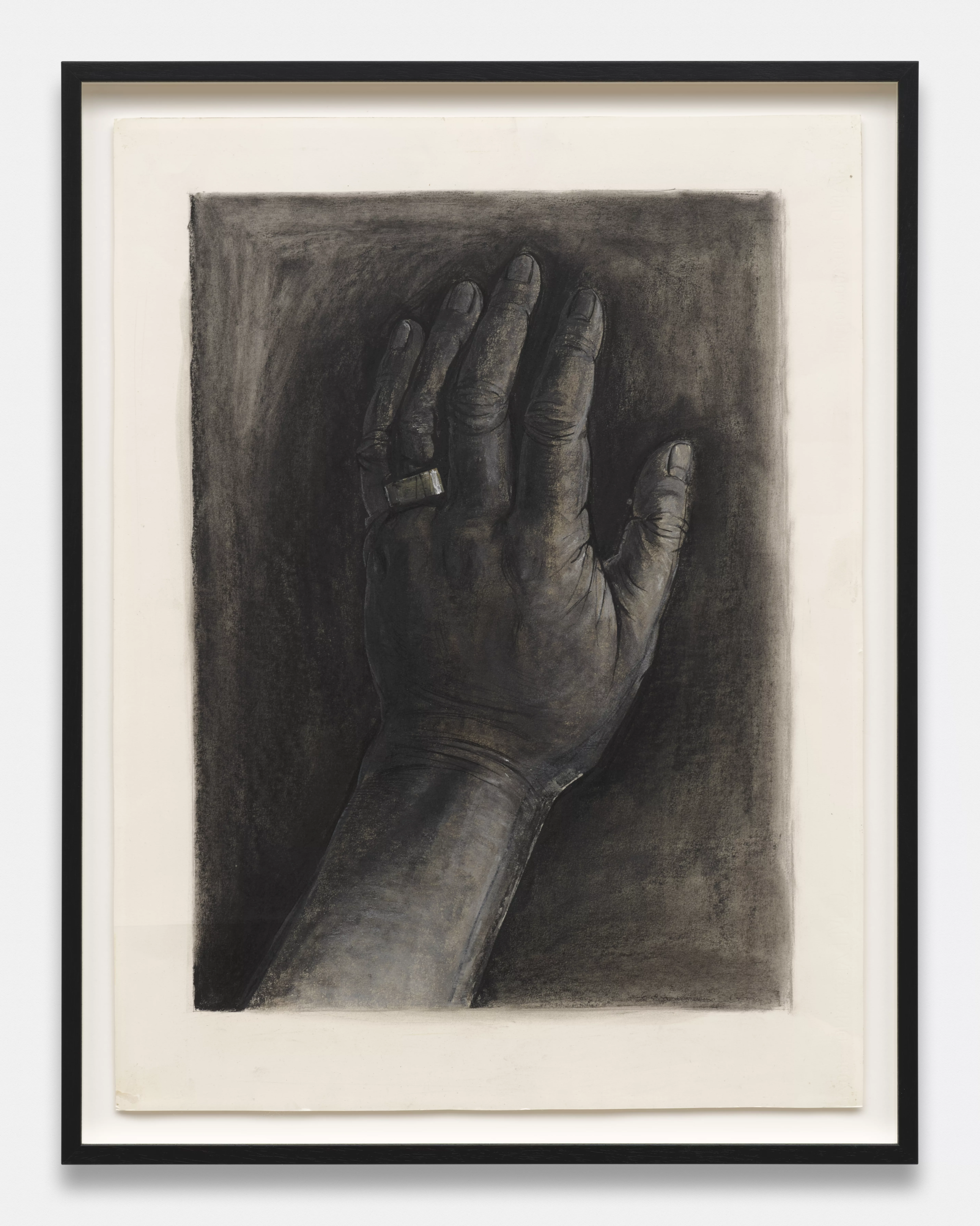

Nearly a decade on, both beliefs have been proved right. Since 2016, the charity White and Shaw co-founded, Hospital Rooms, has worked with forty four mental health facilities across the UK – from a forensic secure unit in Norwich, to a mother and baby unit in Exeter and a unit for people with dementia in North London. For each location, Hospital Rooms commissions gallery-quality works from leading artists. And from the get-go they thought big. Their very first project, for instance, saw Nick Knight, Gavin Turk, and Turner-Prize winning collective Assemble create site specific artworks for the Phoenix Unit, a rehabilitation unit for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Since then, Hospital Rooms have commissioned bespoke work from Mark Wallinger, Jade Montserrat, Tschabalala Self, Richard Wentworth and Harold Offeh, among many other world-class contemporary artists. As if this wasn’t enough, this year the charity launched a national Digital Art School programme to bring online creative workshops and art materials to NHS mental health hospitals in England. As of May, all 58 Mental Health Trusts in England have participated in the programme, meaning Hospital Rooms have successfully been able to deliver artist-led sessions and art boxes to every NHS inpatient mental health site.

Photo © Hospital Rooms (Tim Bowditch)

Given this success, it may come as a surprise that there was a time when White and Shaw thought they wouldn’t be able to get Hospital Rooms up and running at all. “In the beginning no-one wanted us to do a project with them,” the pair tell me. “We were asked, ‘where’s the data to say what you will do will be beneficial’,” they explain. “We were also told that bringing artists onto wards and leading workshops wouldn’t be possible in an inpatient ward”. It started to seem like their dream would remain just that. “It took 18 months to convince one NHS trust to work with us,” White and Shaw say. Eventually though, medical director Dr Emma Whicher (now one of Hospital Rooms’ trustees) gave them the opportunity they needed. And once the press and, even more crucially, the patients at the Phoenix Unit saw the results of Hospital Rooms efforts, the ball really started rolling. “Things are very different now, and we are inundated with requests for projects,” White and Shaw admit. “It took us a year-and-a-half to get the first project off the ground,” they note, “but since then we’ve never looked back.”

Two years ago, Hospital Rooms got another boost, in the form of a partnership with Hauser & Wirth. Committing to raising £1m for the charitable organisation by 2025, the gallery is now also playing host to a new interactive exhibition, which offers the public the chance to enter Hospital Rooms’ world and participate in their work. Essentially, ‘Digital Art School’, at Hauser & Wirth’s Mayfair space, recreates Hospital Rooms’ Digital Art School format, allowing visitors to join in creative workshop sessions led by artists such as Abbas Zahedi and Eileen Cooper, and watch art activities projected onto the walls of the gallery, which are also hosted by artists and designers including Giles Deacon and Sutapa Biswas. But, really, the exhibition is much more than a public space for interactive screenings – it’s the entirety of Hospital Rooms’ project in microcosm.

Walking in, colour washes over you. Gone is the traditional white cube; here, two walls are coated in pink and teal, while, across the room, over 2000 sheets of paper are pinned from floor to ceiling. Representing just two weeks of artistic activity that the Digital Art School makes possible in hospitals across the country, these sheets of paper will be transformed as the exhibition goes on, swapped out for visitors’ drawings. Plants hang from the roof and bookshelves sit next to artworks on one wall. The whole space feels bright and inviting – more like a living room or an artist’s studio than a Mayfair gallery. Which is, of course, exactly the point. Hospital Rooms have transformed Hauser & Wirth just as they do mental health units, making the usually cool, ordered space into one of creative play. “We have learned more and more how important it is to have exhibitions and public facing events,” White and Shaw say, when I ask them about the role public exhibitions like this one have in their wider project. “Very few people, other than the people who are patients or staff in the hospitals we work in, will get to see the artworks made in the projects,” they explain, “and the exhibitions are a way to share this work and have conversations about the problems with the mental health system and how art can play a part in improving and destigmatising severe mental illness”.

There’s a very real practical purpose for the exhibition too though. Alongside the books, plants and free art materials at Hauser & Wirth are artworks from leading contemporary artists: a chair by Martino Gamper, for instance; a glossy Maisie Cousins photograph; a sunny painting by Sola Olulode. All these works – every single one on display throughout the duration of the exhibition – are up for auction. Digital Art School culminates in a live fundraising auction at Hauser & Wirth London, hosted in partnership with Bonhams, on 11 September, and an online-only auction at Bonhams.com the following day. Both auctions will showcase works donated by artists across the UK, and all of the proceeds will go towards Hospital Rooms’ upcoming work, including a number of as yet undeclared projects that Shaw and White tell me “will be taking place in Yorkshire, Birmingham, Bristol and London”.

This isn’t the only way the artwork at Hauser & Wirth will live on in future Hospital Rooms’ work though. One of the standout features of the Digital Art School exhibition is the floor. Swathes of colour spill across the gallery: sunny yellows, warm pinks and pops of blue. It’s as if the whole building has been turned upside down, the gallery floor transformed into a vivid sky, held evocatively at sunrise or sunset. This is an adaptation of a mural by Nengi Omuku, which was originally created for a 60 square metre gym wall at Hellesdon Hospital in Norfolk, as one of Hospital Rooms’ commissions. “The mural was inspired by a workshop I led with Hospital Rooms in October 2023, where service users were invited to create collages representing things that bring them joy, using cut fabric and paper,” Omuku explains. “One artwork that particularly resonated with me was a hot air balloon crafted by one of the participants,” she adds. “He described the hot air balloon as a symbol of freedom – representing his desire to break free from the constraints of his mind and the challenges that led him to this place.” When this participant asked Omuku if she could include hot air balloons in her Hospital Rooms’ mural, she “wholeheartedly agreed”. Now, at Hauser & Wirth, these hot air balloons from Omuku’s original sky design have cleverly been turned into bean bags – symbols of comfort and ease as well as freedom. After the exhibition, these will return to Hellesdon Hospital, to be united with their painted counterparts and the patients who dreamed them up.

Given the charity’s origin in a personal story of seeking to make a friend’s life better, it shouldn’t really come as a surprise that mental health inpatients are at the heart of the Hospital Rooms project. Yet, this is also what makes their work so radical. “There are still lots of misconceptions that things are the way they are for good reason,” White and Shaw profess – “that patients should have white or magnolia walls, and low stimulation in every space, and shouldn’t have things around them that challenge them.” Over 25 projects and thousands of patient workshops later, they have found “this is far from true”. This is not to say that every patient’s feedback has been the same however – far from it. “We have seen patients react differently to the wards they are in,” White and Shaw say. “Sometimes people in the wards are less embarrassed having visitors, some find rooms that speak to them and find escapism or joy in certain artworks,” they add. “Some people who have taken part in the projects have gone on to have a very meaningful relationship with art and making.”

These meaningful relationships go both ways too. Many of the artists who have created site-specific works with Hospital Rooms also profess to have found the experience life-altering. “I cannot speak highly enough of the work that the whole team at Hospital Rooms achieves through working with artists and medical teams in mental health care, across our NHS mental health care units here in the UK,” Sutapa Biswas tells me. Since the 1990s, Biswas has developed a number socially engaged projects in collaboration with various museums and arts organisations, alongside her studio practice. “Between 2011 and 2018, through my work as an academic teaching within art schools in HE, I witnessed first hand the psychological impact that government austerity policies in the UK, and world events – the rise of a toxic male culture for example – was having on the mental health of my students,” she says. This experience, which Biswas described as “deeply distressing”, combined with the tragic loss of someone close to her to suicide, was what “really made me want to support the work of Hospital Rooms within mental health care,” Biswas declares, adding that she strongly believes “that art enriches, and has a huge part to play in all walks of life, including mental health care.”

Biswas’ first collaboration with Hospital Rooms was in 2017, when she was commissioned to undertake a mural of a garden for the ‘Women’s Room’ of the NHS Garnet Ward, Whittington Hospital, which was used by elderly and Alzheimer’s patients. “The idea came about through my long-standing love and fascination for gardens, and through some initial discussions with some of the elderly patients in the ward,” Biswas tells me. “Due to the fact that the in-care patients were not able to visit the outside without supervision, and the exterior spaces immediately outside the windows felt bleak, what I wanted to achieve was to create a sanctuary of sorts, that patients could sit in surrounded by images of trees and plants.” Attempting to bring the outside in, Biswas says it was “both fascinating and incredibly moving” for her to discover “from many staff that they too would sit in this ‘space’ during their breaks for solace and comfort”. This, perhaps more than anything else, affirmed for her “the huge importance” of the work that Hospital Rooms does. “I have seen first hand how the work they do within these contexts really impacts positively on patients, visitors and staff,” Biswas stresses.“Hospital Rooms is all about transformation,” artist Susie Hamilton echoes. “The work of Hospital Rooms artists, as painters and workshop leaders, can bring inspiration and understanding to people going through very tough times,” she adds, by “replacing the dullness of dingy walls with radiant, imaginative vistas and thereby helping to change people’s lives.” Like Biswas, it was this capacity to change lives that prompted her to work with the “amazing” charity. “I know how art can turn things around,” Hamilton says simply, “using the very experiences that seem so difficult or unacceptable to make work that is vivid and forceful, and in so doing to turn feelings of inertia or helplessness into a sense of purpose, dynamism and even, at times, joy.”

Words by Eloise Hendy