The fate of the condiment is to always be the supporting act and never the star. The lonely bottle must resign itself to cheering on the key players on the plate from the sidelines. From ketchup to soy sauce, mustard to wasabi, condiments complement rather than command. Despite their reticence, though, the continual presence of these products at the dining table actually gives them a unique power as the mainstays among an otherwise rotating cast of ingredients. Applied to sweeten, to salt, and to spice, they appear again and again, even as tastes shift and recipes change. It is rare for a new player to join their long-established ranks, but since launching in 1997, one brand has moved from a single woman’s kitchen to the shelves of millions around the world.

“In the last ten years Lao Gan Ma has shifted beyond a cult following and into larders around the world”

Mention Lao Gan Ma (老干妈)

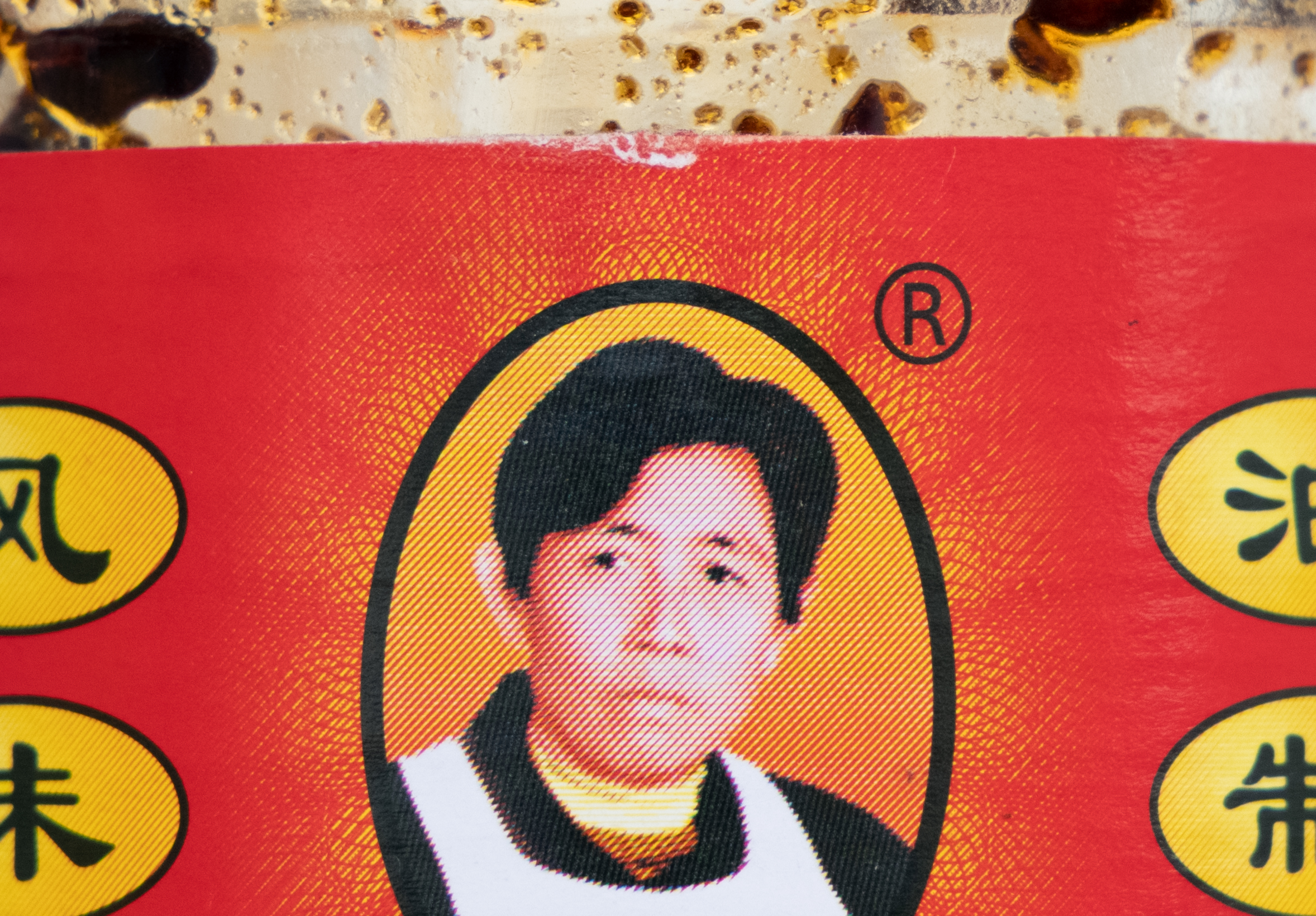

, a brand of chilli oil founded in Guizhou in China by Mrs Huabi Tao, and those in the know will respond with almost evangelical devotion. It is an apt metaphor for a brand that has established its visual language through the iconography of Tao’s own image, which looms like the Virgin Mary from the label of each jar. The founder is displayed proudly as a mark of quality on each and every one of the company’s products, a white apron tied over a stylish roll-neck jumper and loose black shirt. Her face is notably stern, at turns irritated, stoic or pensive, depending on which exact angle you catch her at. Her dark hair is neatly swept to one side, and her nickname of “old godmother” (Lao Gan Ma) is emblazoned beneath.

Branding is key for a condiment to stand out as it jostles among the countless competitors upon the shelves. They must make use of immediately recognisable graphics, which need to be both easily repeated and eye-catching. Lao Gan Ma opts for a bright vermillion red for their label, while the portrait of Tao sits emblazoned against a radiant yellow backdrop within an oval frame.

The particular choice of colours and the circular portrait format are reminiscent in their design of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book, which typically features a portrait of the Communist Chinese leader on the cover. First published in 1964, the book is representative not just of the country’s political system but the highly effective means of dissemination and communication that they have long relied upon. One of the most famous symbols of China internationally, the BBC named it an icon of propaganda in 2015, and more than a billion copies of the distinctive red vinyl covered book have been printed. Lao Gan Ma’s design is similarly iconic, the face of its founder easy to spot at a glance.

Since its launch almost 25 years ago the brand has experienced a remarkable boom. In the last ten years it has shifted beyond a cult following and into the larders of chefs and home cooks alike around the world, notably in the UK and US. Its growth in popularity can be put down in part to a new wave of Chinese diaspora who recommend the brand’s products to non-Chinese friends, while the development of social media has enabled these word-of-mouth tip-offs to travel much, much further.

The Lao Gan Ma Appreciation Society on Facebook has almost 4,000 followers, a hoodie inspired by the brand can be bought on eBay, and there is even a zine dedicated to the sauce. “Old Godmother, the woman; the legend,” one fan writes in the Facebook group, while British chef Alex Rushmer left no doubt over his devotion when he wrote on Twitter last year, “I would eat a bowl of gravel smothered in Lao Gan Ma.” In 2018 the American wrestler John Cena shared a YouTube video in which he praised the brand in fluent Mandarin.

The appeal of Lao Gan Ma lies in its remarkable adaptability: it’s as delicious on a bowl of Chinese noodles as it is on a fried egg on toast. This easy movement between cuisines, from Chinese to Western, speaks to the broader question of national identity with which condiments are so frequently tied up. Ketchup, wasabi, soy sauce and mustard are linked with the culinary identity of their respective countries, and represent more than just simple seasoning.

Interestingly, ketchup comes from the Hokkien Chinese word ‘kê-tsiap’, the name of a sauce derived from fermented fish. Traders brought the fish sauce from Vietnam to southeastern China, where it was encountered by the British and eventually popularised in the west as tomato ketchup in Philadelphia in the early 1800s. The Heinz logo was riffed upon as an icon of American popular culture by Andy Warhol in his silkscreens of 1964, demonstrating not only the power of design when it comes to the branding of condiments but the fierce nationalism that is often associated with them.

“Huabi Tao’s image looms like the Virgin Mary from the label of each jar”

Lao Gan Ma’s success in the west is unusual for a brand that is entirely marketed in Chinese, with labels displaying no English beyond the small print. Chinese characters adorn the front of each jar, relying on the visual cues of the design for an international market not accustomed to reading other languages. It is a resolute yet risky strategy that has decidedly paid off.

Lao Gan Ma now produces 1.3 million bottles of sauce daily, with exports to more than 30 countries. In 2015 Forbes calculated the 73-year-old founder’s wealth at $1.05bn. The company saw its annual sales revenue reach a record high of more than $835.6 million in 2020. From its deeply savoury chilli black bean sauce to the delicate crunch of its crispy chilli oil, in just a few years Lao Gan Ma has developed a powerful brand recognition that most could only dream of. Against the odds, Lao Gan Ma has broken out from the supporting cast into a leading role.