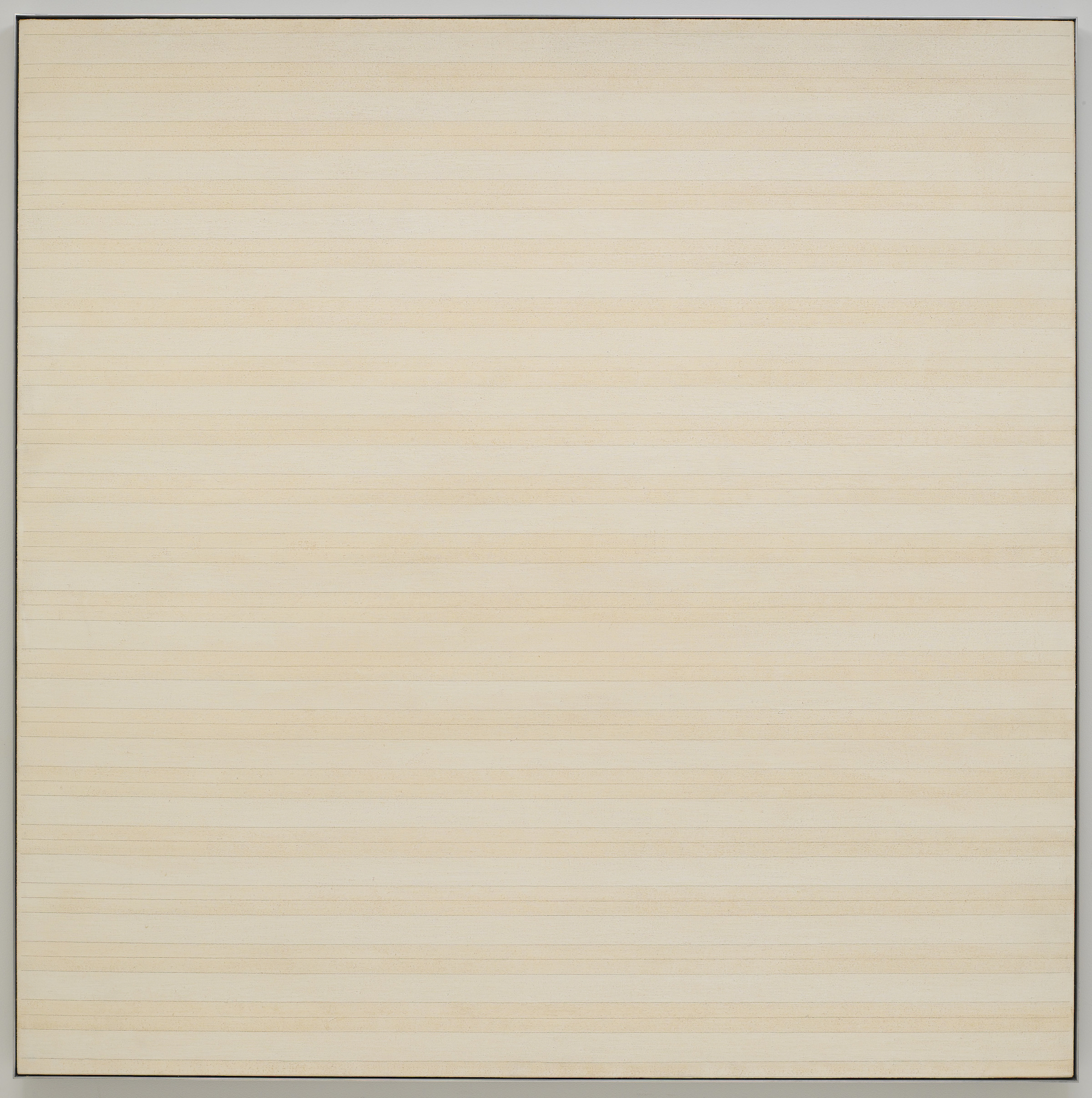

Agnes Martin, Desert Flower, 1985 © Estate of Agnes Martin /Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This Artwork Changed My Life is a fortnightly series of personal essays that share the stories of life-changing encounters with art.

I discovered Agnes Martin on an ill-fated trip that my father and I took to visit my sister in San Francisco. I was mired in an unfamiliar, all-encompassing feeling which would later be diagnosed as depression, though the term feels strange and inaccurate to this day. I felt everything and nothing, and I didn’t have the language for any of it. As soon as we walked out into the California sun, I wanted nothing more than to go home, back to London. My awareness of that selfishness, alongside my father’s twinned concern and anger, numbed me into a sullen inertia.

During the day I would lie in my sister’s bed, listening to the acrid whirr of the air conditioning. She would return from work every evening and hand me a cup of half-melted frozen yoghurt which I would eat, propped up like an invalid, as she talked to me about her pedantic colleagues. My father would hover in the doorway, frustrated by my apparent sullenness, newly alienating aspects of my behaviour which I had no interest in explaining for his benefit.

There is an almost 60-year gap between myself and my father. At the time of the trip, he was in his late 70s and I, at the age of 20, was on the verge of dropping out of university. He and I have a few set topics that we talk about (books, plays, my siblings). Otherwise we sit together in companionable, if vaguely awkward, silence. He is a particular man, with habits that have calcified as he has gotten older. He gets angry when you renege on plans last minute. He hates it when you cry. I have an acquiescent streak and so we rarely have arguments, but when we do he will remove himself completely from the conversation, either walking away as you are speaking or simply pretending not to hear you.

“There is something reserved about Martin’s work, something ostensibly impassive, but with a sense of buoyancy too”

On one of my more capable days, he and I went to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He was frustrated with me for something and I didn’t much care, so we were on our own, separate tracks through the gallery. I have always liked the idea of looking at art. I like the fact that it will trick me into being thoughtful, serene and mysterious, instead of what I really am (impatient, irritable, slouched). But I am often overwhelmed by art, like every nerve ending has been exposed, before that collapses into a kind of childish resentment at not being able to parse what is in front of me. I am not proud of that.

I don’t believe art should have to be instantly legible to its viewer. I used to attribute my inability to “get” art to the art world’s exclusivity, and while I still believe that to be partially the case, I can see now that my own impatience and youthful arrogance also contributed to me not wanting to engage with anything that wasn’t immediately comprehensible. Inevitably, the artworks I responded best to when I was younger were the ones that appealed to some immediate, fleshy gut instinct: like the dimly lit room of Rothkos in the Tate Modern, which feels like being ensconced in a womb, or L’Orangerie in Paris, where Monet’s water lilies wash coolly over your skin.

I found myself, almost by accident, in one room, surrounded by a series of square pastel canvases in soft focus. I had never heard of American painter Agnes Martin before. The pieces all seemed to have been composed out of the same few rudimentary parts: pale washes of colour, scored through with pencil-drawn grids, horizontal and vertical lines criss-crossing. I was drawn first to the colours: eggshell blues, flushed pinks, speckled creams, and then to the lines. I felt cushioned by the work, supported by it, but there was also a profound sense of release. There is something reserved about Martin’s work, something ostensibly impassive, but with a sense of buoyancy too.

Art historian Nancy Princenthal wrote in her intimate biography of Martin that the artist’s work exists in “the most extreme forms of abstraction: pure, silencing, enveloping, and upending.” The totality of Martin’s work is what I found irresistible: it was pure sensation, nothing overly cerebral about it. Her work engulfs you completely.

Desert Flower, a 1985 piece, was one that I felt particularly drawn to. It follows a simple pattern with two slimmer rows of a warm, peachy sand colour, and then one thicker row of a slightly cooler buff shade, repeated. Martin always rejected literal interpretations of her work: “Beauty is unattached, it’s inspiration,” she said. Desert Flower still evokes to me an expanse, swathes of space, the horizon stretching out, the feeling of sky and sand, if not an actual representation of it. An undeniable sense of freedom, even if you cannot quite see it.

Martin’s grids, drawn with soft pencil, feel like they should lend themselves to restriction. Instead there is a sense of porousness and possibility to them. Martin often drew these lines with a ruler, but if you get up close you can see the inevitable wavers that come from drawing with a human hand, a sense of fallibility. Curator Nancy Spector draws attention to the “fragile, almost dissolving lines, and hushed tones.”

“Martin’s grids are guiding lines, a steady, low constant, like a warm hand resting on the back of your neck”

The compositions seem so simple, so pure in their distillation of colour and still so precisely unique, so human. There is a gentle rhythm to these grids: they are guiding lines, a steady, low constant, like a warm hand resting on the back of your neck. Looking at them in the museum, the pressure on my temples had eased. Martin had granted me some modicum of peace.

I don’t remember where my father was. I sat in the room for as long as I could, not wanting to succumb to the heaviness again. I found him waiting in the foyer, holding a gift shop bag. “I wanted to get this for you,” he said, with awkward emphasis, and pushed it into my hands. I opened the bag to find Princenthal’s biography of Martin, a hardback swathed in the colours I had felt so drawn to just moments before. “I wrote something in it,” he said. I opened the book, the spine crackling a little. There, on the title page, written in his near-unintelligible scrawl:

“To my Ava. To remember a happy hour visiting SFMoMA. July 26th 2016.”

Ava Wong Davies is a playwright and theatre critic based in London