In 1847, John Ruskin arrived in a wet and rainy Venice, eager to begin research for his upcoming study, The Stones of Venice (1851-53). Upon reaching his hotel, Ruskin soon discovered the appearance of another noted academic, one whom also held some notoriety within the tightly wound circles of the British intellectual elite. Anna Jameson, Irish immigrant turned critic and art historian was staying at the same hotel; she too was gathering notes on Venetian painting for her soon-to-be-published tome, Sacred and Legendary Art (1848).

Despite the novels to Jameson’s name and her deep understanding of how to look at and write about art, Ruskin had in 1845 taken his pen and pronounced in a letter to his father that Ms Jameson “knows as much of art as the cat.” Behind this sneer is a simpler message about who can and can’t write about art. As a woman born of comparatively simple means, Jameson’s trajectory into the upper echelons of nineteenth century intelligentsia was uncommon, and Ruskin’s distaste a mirror to the attitude held by the society Jameson moved within.

“Cain’s writing feels more urgent than a lament on the gendered history of art writing”

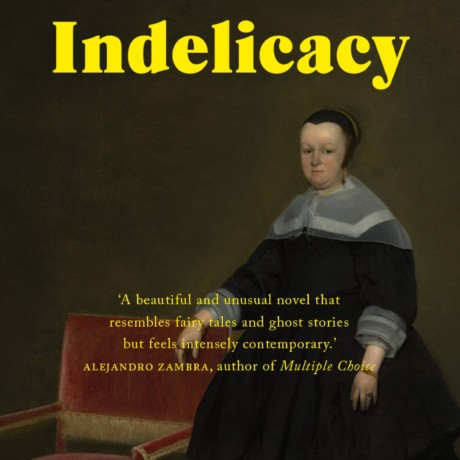

It is a similar but uncanny world in which we find Vitória, a museum cleaner who stars in Amina Cain’s debut novel, Indelicacy, published in February this year. Set within an undefined period and in an unknown geographical setting, Cain blurs the lines between history and modernity. While this isn’t the nineteenth century (or is it?), the streets are lit by gaslight and the rich travel by horse and carriage. The poor, like Vitória, scrub the floors as women in silk dresses look at the art hanging on the museum’s walls. At the end of her working shift, Vitória sits down at her table and writes about the paintings she has seen before falling asleep and waking at dawn. “My rooms were small with hardly any furniture, but what was there was nice enough, if simple, and I kept it neat as a pin,” she describes. “A bedroom with a bed and a blanket. In the kitchen, a table and two sturdy chairs.”

This existence is one shaped by longing, although this longing is unmoored. It takes the form of clothes, objects and social status, with Vitória later entering into an agreeable but ultimately passionless marriage with a very rich man. On looking at a painting of Mary hunched over her table, Vitória writes: “she appears as if she’s in ecstasy. I wonder what that feels like.” Even in her new, wealthier existence, Vitória’s writing is gently mocked as little more than a flippant hobby, her “writing room” soon becoming a drawing room shared by the household—an uneasy and contested threshold within the supposed domestic bliss the house offers. Vitória plots her escape, but remains unsure of what exactly she is escaping from.

At first glance, Indelicacy is a novel in the same vein as Virginia Woolf’s essay A Room of One’s Own (1929), but it feels frank and deliberately relevant to today. The fictional life of Vitória and the lived experiences of Anna Jameson both reflect the age-old question of who gets to write about art and why. While ekphrastic writing in the novels and romances of women writers have been known to exist since the early seventeenth century, these stories have been buried when compared to the prolific distribution of classical male-and-stale writers of the time. Instead, the history of women’s writing is trickier, muddier even. Rather than the published tomes of Pliny the Elder or Giorgio Vasari’s artist biographies, the story of female texts on art exists in scraps to be found in the diaries, letters or fiction that history has been able to salvage.

Yet Cain’s writing feels more urgent than a lament on the gendered history of art writing. For both Jameson and Vitória, their proximity to art affords them a step towards high society, with Vitória meeting her husband whilst at work within the museum: “It’s strange my husband noticed me, but he came to the museum to see the paintings of Caravaggio and then of Goya and the third time I was mopping the floor of the coatroom when he came for his jacket and umbrella.” It’s a clever meet-cute, but also a snarling suggestion of the capital afforded by proximity to art. A Cinderella story, only with more bite.

“Cain reveals that Vitória’s freedom is found not in the writing room, but by opting out of cultured society altogether”

Class certainly isn’t a facet of life that Vitória is blind to, with the protagonist keenly aware of the territory she has at once left and remains bound to: “the women working in the glue factory, I think of them often. Why was I saved from that life, from a mass of dead horses?”

Through Cain’s writing we deftly explore Vitória’s growing numbness to the materialistic values she once gave in to, and watch as she begins to treat her own life as if from a distance. “To eat dinners and sit in restaurants. To sleep with my husband and then tell Solange which rooms need cleaning. To clean my own study and then read in it. To sit in a dark theatre with a stage lit in front of me.” Her writing turns away from art, and inwards towards herself and her routines, as if her own existence can be seen from above, like a miniature portrait on a museum wall.

Indelicacy moves beyond the ideas of A Room of One’s Own, as Cain reveals that Vitória’s intellectual freedom is found not in the writing room she is afforded, but by escaping the upwardly mobile class trajectory and opting out of cultured society altogether. She moves away. Brings her desk. Looks from her window in the countryside and out into an open field. This is not domestic bliss; it is boredom. The pages end with Vitória content, “still in the process of becoming, the soul makes room.”

“Cain’s intention is not to chronicle the death rattle of the culture sector, but she provides a dark fable for our times”

Against the backdrop of Covid-19 and the thermo-nuclear meltdown of the arts sector, Indelicacy feels both uncomfortably close to the bone and a parable of an art world not too far removed from our own. In the world Indelicacy occupies, a working class museum cleaner chances upon wealth and is still unable to attain the freedom to write. In 1845, an upwardly mobile art critic is mocked openly by her male peers.

More than a century later, and the art world continues its struggle to uplift silenced voices, with museum cleaners and front of house staff, many of whom are disproportionately BAME and/or working class, facing redundancies and job losses at institutions such as the Tate, Royal Academy and Victoria & Albert Museum within an industry that promises the opposite: enlightenment.

Cain’s intention is not to chronicle the death rattle of the culture sector (who would have known the world would be as it is now), but what Indelicacy provides is a dark fable for our times, rich in its appreciation of art and alert to the false promises the art world has to offer.