There is a tenderness to being read a bedtime story by your mother as a child. Bedtimes in our household (as in many) weren’t smooth sailing. In an attempt to make sleeping in my own room an adventure, my mum purchased a classic IKEA bed with a twist. A lightly coloured wooden bunk bed, suspended in midair, was installed in my room with a slide attached, which occupied nearly the entirety of the floor.

I can remember how many invented games revolved around that bed. The empty space underneath the bunk bed became a secret cave. We transformed the slide into a jungle gym, creating an obstacle course which required us to climb onto the top bunk and descend down the slide as quickly as possible, one after the other. There are photos of me on the bunk with arms wrapped around my childhood best friend and gleeful ear-to-ear grins on both our faces. I know that bed was a source of ecstasy and fantasy while I was growing up, but the first week of its existence in our house was a different story.

“I discovered the potential of artworks to mirror and encapsulate the emotions which I could not express through words”

That photograph of my best friend and me, caught in a state of pure bliss together, represents a lightness in my childhood. But there are many other photographs from that time in my life where I am frowning or tearful, which paint another picture altogether. I was a child riddled with anxieties and a chest full of fears. I was often disgruntled and perturbed by my surroundings. It is hard for me to discern how much of my early childhood was coloured with discomfort and how much I’ve rewritten in hindsight, with the knowledge of the chronic mental health conditions which have come to characterise much of my life.

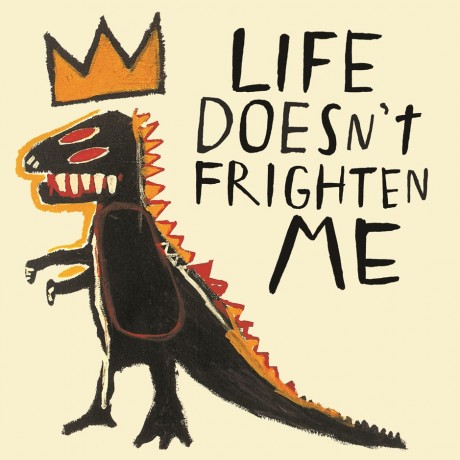

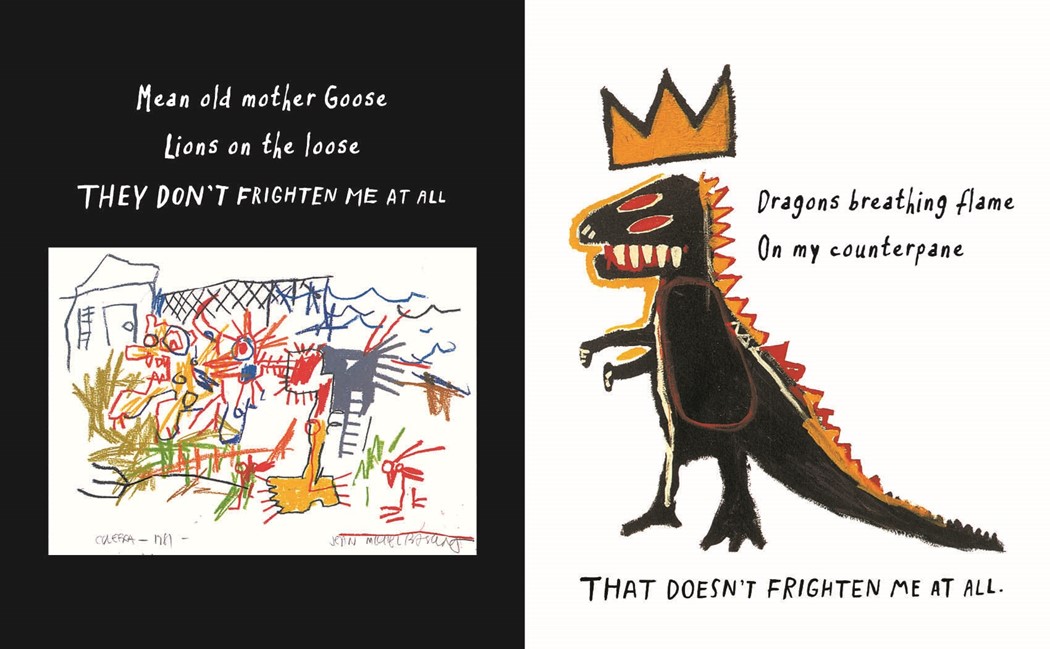

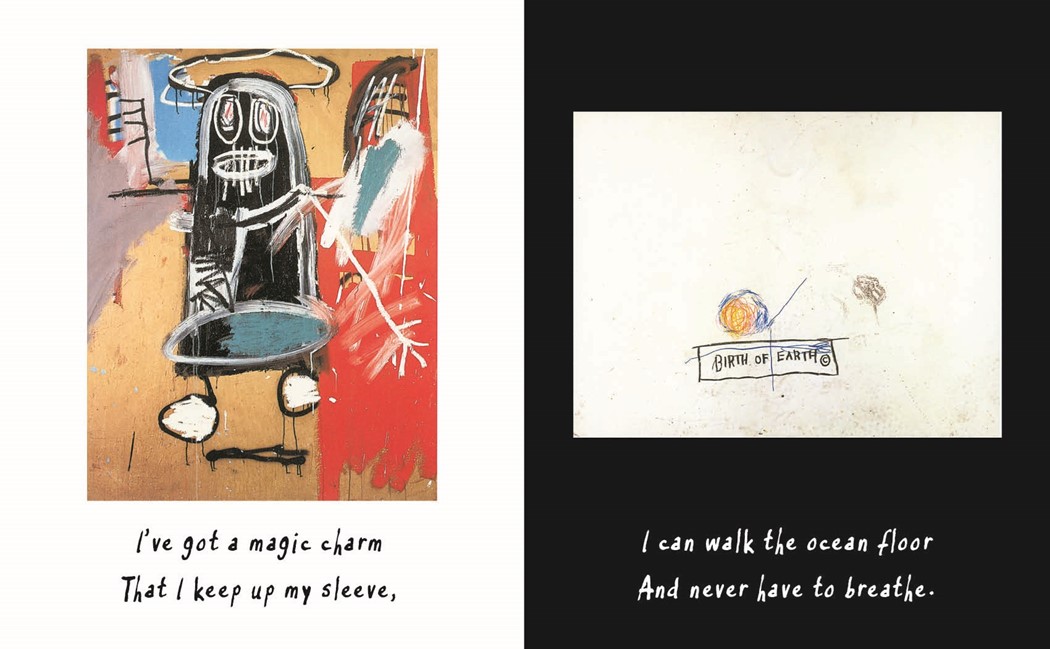

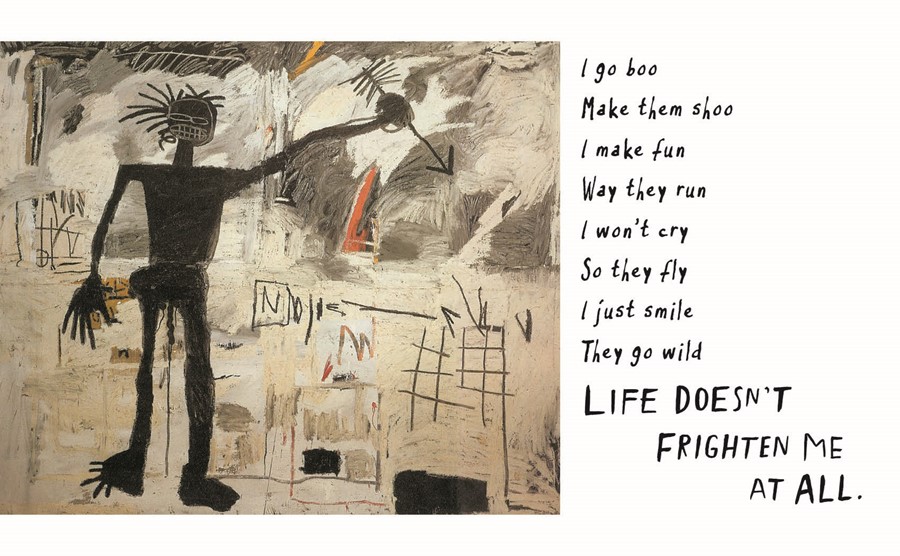

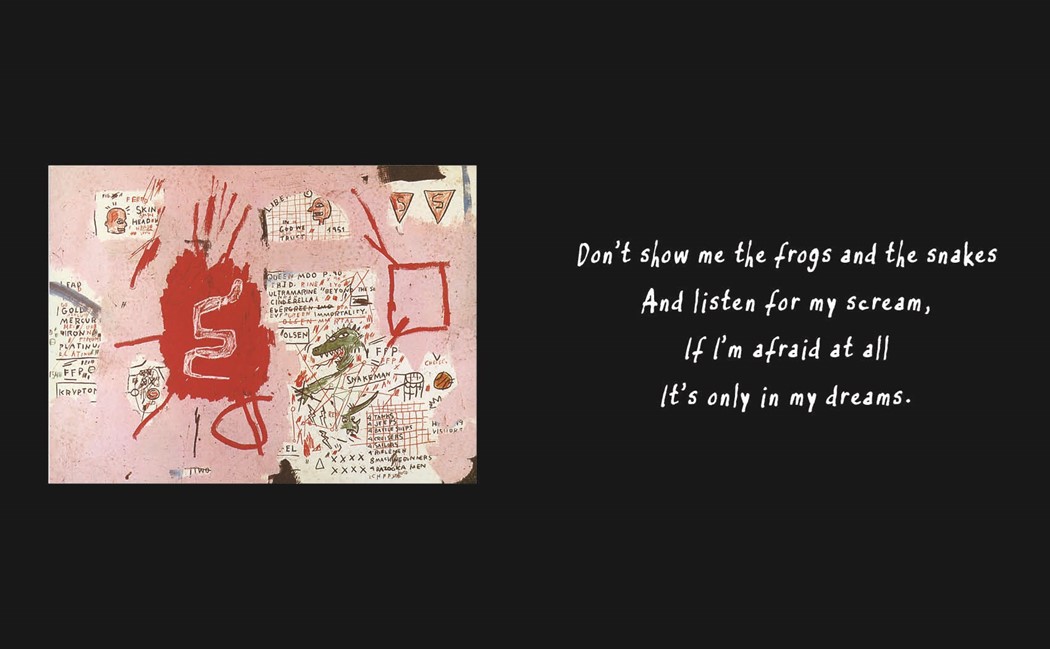

Spread from the 25th Anniversary Edition of Life Doesn’t Frighten Me. Courtesy Abrams Books

That first week in my new bed, at least, is where my mum’s memories and my own align. Exciting and adventure-filled, the bed was chosen as a ploy to lure me into sleeping on my own, but in the first week of its existence it barely fulfilled its role. As a toddler I was endlessly frightened by the possibility of monsters lurking under the bed and I persuaded my mum to stand holding my hand until I fell asleep. The height of the bed meant that she was unable to sit and so would nod off in a vertical position, threatening to topple over. In a state of desperation, wanting to end the pattern of standing guard as my protector, she dusted off a children’s book in the hope of remedying my nighttime affliction.

The illustrated version of Maya Angelou’s Life Doesn’t Frighten Me, published in 1993 and adapted from the original story first published in 1978, sees Angelou’s words paired with the distinctive drawings of Jean-Michel Basquiat. It opens on a double-page spread, with white cursive writing framed on a black background: “Shadows on the wall, Noises down the hall.” On the adjoining page sits an artwork in darkened hues of black, grey, red and deep purple, and what I now recognise as the familiar “paintmanship” of Basquiat. The artwork depicts a red face with the characteristic symbol of a crown atop their head, hollow, threatening eyes and a criss-crossed mouth resembling a mask.

In an instant, all the invisible monsters lurking under my bed were given a clear and distinct image. Yet upon turning the page to the next spread, the mood of the book has transformed. Now, that monstrous character has emerged out of the shadows and revealed themselves to be an angel of the night. Arms outstretched, that criss-crossed mouth has shifted into a wide smile, surrounded by hasty, bright brushstrokes as if sparks of light are bouncing off the figure, complete with a halo floating above their head. Accompanying the artwork is the defiant declaration: ‘Life doesn’t frighten me at all.’ Across the next pages Angelou and Basquiat detail an array of fearful scenarios, from bad dogs barking loud to big ghosts in a cloud, panthers in the park to strangers in the dark, before announcing confidently after each one that, yes, life still doesn’t frighten me at all.

“Basquiat’s illustrations demonstrate the power of art to translate our own internal emotions, isolating and tumultuous”

At the age of 26 I am now closely acquainted with Basquiat’s oeuvre. I recognise his semiotics and,can easily distinguish his work at a glance. Yet as a young child, Life Doesn’t Frighten Me represented one of my earliest engagements with any artist. Of course there were artworks and illustrations to be found in many of my children’s books, but with Basquiat and Angelou I found something different, something mind-bending and completely novel to a four-year-old.

In my first introduction to Basquiat I discovered the potential of artworks to mirror and encapsulate the emotions which I could not express through words. By the time of publication of the special illustrated edition of Angelou’s book, Basquiat had already been dead for five years., but it was as if his creations were inside my head and vividly alive. All the uncertainties and anxieties which had previously plagued my bedtimes were simultaneously given a name and dispelled. What was this magic language that I had come across?

“It was through this book that I was able to reach the undeniable conclusion that, even in our darkest moments, we are never truly alone”

I now work in the arts, starting out first as a curator, attempting to build platforms and environments for artworks to reach more people, then as a writer, communicating my own interpretation, and finally as an artist in my own right. When I think of the reasons that I was compelled to start working in this creative field, I come back to how integral art was to my early life. As an artist herself, my mum spent the initial years of my childhood dragging me unwillingly around exhibition after exhibition, including a major retrospective of Basquiat at the Serpentine in 1996, when I was just 18 months old. Though at the time I resented being pushed through strange, white-walled buildings filled with even stranger pictures, I now recognise how formative my exposure to art at an early age really was.

Basquiat’s illustrations in Life Doesn’t Frighten Me demonstrate the power of art to translate our own internal emotions, isolating and tumultuous, into the external world for others to see and understand. The real magic comes with the moment when a person views a subjective artwork, something inextricably personal to the artist, and sees their own self reflected back. Through painting and drawing, strangers are able to speak to one another. They can share stories and share fears. It was through reading this book that I was able to reach the undeniable conclusion that, even in our darkest moments, we are never truly alone.

Jamila Prowse is an independent curator, writer and editor based in London

Maya Angelou, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Life Doesn’t Frighten Me: 25th Anniversary Edition

Published by Abrams Books in 2018

VISIT WEBSITE