When Lois Stonock, artistic director of Brent Borough of Culture, was consulting young people earlier this year about plans for Brent 2020, she asked what culture meant to them, and where they might think about going to experience it. “None of them had heard of the Tate of the National Theatre,” Stonock remembers. “They knew about the Southbank Centre, but just the skatepark, not as an arts space. In this sense, I think in Brent we have more in common with Birmingham than we do with people in Zones 1 or 2 [London’s inner travel areas].”

Such responses may be surprising higher up the city’s cultural hierarchies, but for Stonock, they are the expected reactions of a tightly-knit, multicultural community which feels that London’s larger institutions have little to offer them by way of engagement or programming. With a carefully planned series of events disrupted by the first national lockdown, how now to bring culture to these populations? With autumn’s Brent Biennial, libraries are part of the answer—capitalising on existing community networks to showcase a range of installation, conceptual, sound and visual art to often non-traditional audiences across the borough. Featured artists include Paul Purgas, Yasmin Nicholas, Barby Asante and David Blandy. Works range from Purgas’ delicate soundwork to Visions of the Deep Past, Blandy’s conceptual fantasy world presented in Harlesden Library.

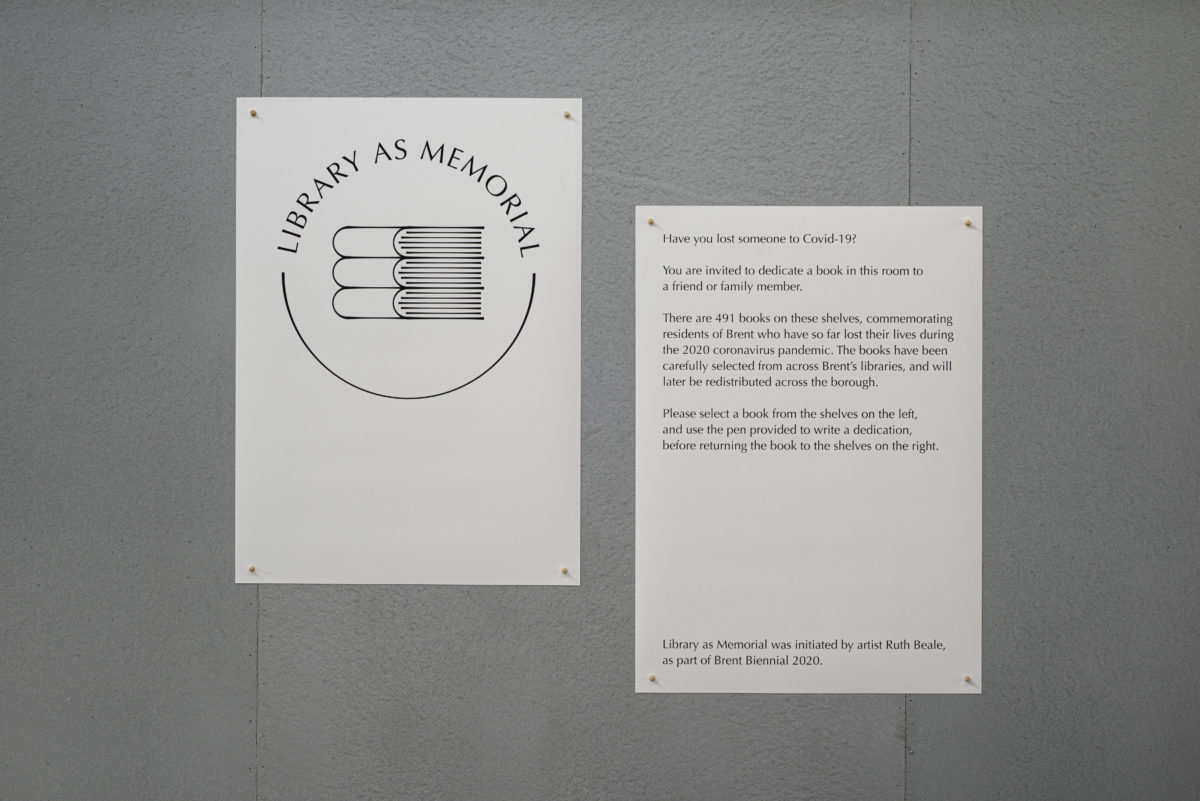

Brent has six council and four community libraries to serve its population of 331,000, which was badly affected by the first wave of Covid-19. In mid-June, ONS figures revealed that Brent had the worst mortality rates from the virus in England and Wales, recording 210.9 deaths per 100,000 people. Up to September, 491 residents had died from the disease, a scarring fact which haunts much of the artwork on display here. The borough’s libraries support their populations—including the most vulnerable—with advice, news, IT equipment, reading opportunities and community initiatives. There is a sense here that those 491 people were not just Brent residents, but likely library-goers, too.

“After weeks of closure, the Biennial is a chance to reinvigorate these spaces with community value”

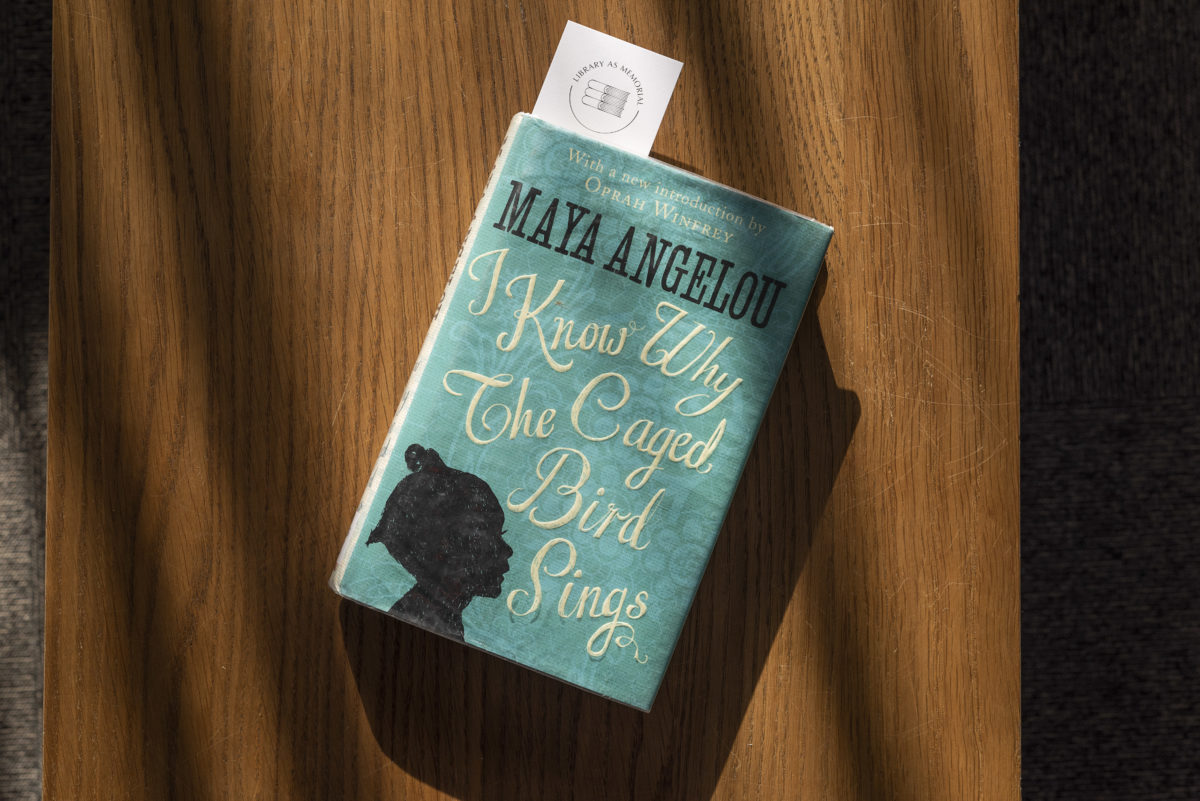

This reality lies at the heart of Ruth Beale’s interactive commission, Library as Memorial, at Kilburn Library. In a quiet side room off the main space, Beale presents a video and installation of books taken from across Brent’s libraries. Six bookcases are marked only by a single sign atop the outside right-hand shelf reading “Filled in Books.” Audiences are encouraged to examine the 491 titles and fill out a dedication slip to commemorate the dead. Several have been filled out so far: familiar titles including Nikesh Shukla’s The Good Immigrant, Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal and Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens. In their own way, all are commentaries on the human condition.

- All: Ruth Beale, Library as Memorial, Kilburn Library, 2020. Courtesy Brent 2020

The room—airy and quiet—has the feeling of an antechapel; a war memorial hangs on the wall opposite the television screen, which shows Holding Breath, a film capturing empty libraries from the inside—upturned chairs, quiet hallways, empty newspaper stacks. The narrator reflects that time has been going faster, not slower, over the past few months. “Remember happy times,” the voice says tentatively, as footage pans from fraying carpets to lonely exhibits and photocopiers, functionless without human contact. “We like having libraries; everyone is there to do the same thing,” the voice continues.

The installation speaks to the dramatic upheaval which has transformed library spaces from community hubs to empty shells—a sequence which has, paradoxically, brought them more into line with traditional art spaces. “At the beginning, we were thinking that the biggest audiences in the borough would be in libraries—and that we could do something there for ready-made audiences,” says Stonock. “What we’ve got now is flipped: it’s more like a gallery—we’re trying to get people to go visit.” Beale’s work therefore exists as something of a hidden commemoration: brought into being by the lethality of the pandemic, but also under-appreciated because of its lasting consequences. It is, above all, a real-time artistic response to the changing nature of public space.

Whereas Beale was able to repurpose her commission within the library space, several artists have faced disruption to their projects because of continuing pandemic restrictions. Brian Griffiths’ work has not been able to open fully at Cricklewood Library for this reason; Dan Mitchell‘s large-scale text work on the glass facade of Wembley Library can now only be seen from the outside, without the context of the library’s information panels.

In response to the closure of Kensal Rise Community Library where he was originally scheduled to give community talks for his commission, John Rogers has created a detailed psychogeographic audiovisual project dissecting the area’s architectural and social history. In one clip (activated by scanning QR codes), a woman explains the changing demographics of several surrounding streets, comprised of dense housing initially built for cemetery and railway workers who gradually made way for wealthier residents. It is a longstanding trend in the city, but is rarely discussed with such proximity to the regions and communities it affects. Libraries are a unique opportunity to start this dialogue.

One clip tells the story of Charles Pinkham, an English Conservative politician who collaborated on houses in the nearby area, giving them their distinctly ornate gables. Pinkham appealed to Andrew Carnegie, then one of the world’s richest people, for an endowment for an extension to Kensal Rise library (opened in 1900 by Mark Twain); he obliged, donating £3000 in 1904. In another, a woman details the 1988 campaign to save the library after the council threatened its closure, which resulted in an occupation: “There was no shortage of kids wanting to stay in the library overnight. The police did come, but we had a fail-safe notice that it was legal to squat in the library—I don’t know if it was,” she remembers fondly.

“The installation speaks to the dramatic upheaval which has transformed library spaces from community hubs to empty shells”

Since austerity was implemented in the UK 2010, over 773 libraries across the country have closed, representing almost a fifth of venues nationally. The number of salaried staff has also dropped dramatically: in 2009, the figure was 24,000; in 2019, it stood at 15,300, with many spaces now being run by volunteers. Central government often shifts blame onto local authorities and favours consolidation of resources, leaving many venues with little choice but to close and be absorbed into new institutions, often without a recognition of the depth of existing community ties. Stonock mentions Ealing Road Library’s unique collection of Gujarati and Tamil newspapers and books, for example. These are spaces which not only reflect but nurture the communities around them. After weeks of closure, the Biennial is a chance to reinvigorate these spaces with their community value.

This gradual erosion has affected the libraries’ ability to look beyond their survival function, says Stonock, creating precarious and often challenging creative conditions. An important distinction lies between council libraries and community libraries: the latter, like Kensal Rise, are completely volunteer-run after being cut off from struggling councils. “The artists working with the community-led libraries are in a context where the institution around them is not there for their artwork in the way that a gallery or museum might be,” reflects Stonock. “They’re there to keep their space open.” Issues around bureaucracy are inevitable: beloved of local government, anathema to artists. Library workers are often immovable from the financial constraints that dictate that money must be spent only where it is most needed; for many, art may not fall under that category.

“Since austerity was implemented in the UK in 2010, over 773 libraries across the country have closed, representing almost a fifth of venues nationally”

For some artists, this community element of curation has been a factor of their work for decades. Carl Gabriel is accustomed to working with councils: the Trinidadian sculptor and photographer has long worked on London’s Diwali and St Patrick’s Day Celebrations, as well as playing a prominent role in Notting Hill Carnival. For him, the Biennial is an opportunity to rediscover the multicultural ties which have diminished as councils have retreated from religious and ceremonial events. His work, a wire sculpture of a humanoid figure reading, is largely featureless—an intentional decision with the aim of enabling a wide audience to relate to it. Perched outside Preston Community Library alongside Gabriel’s more ornate, Caribbean-inspired sculptures, it captures the inclusivity of the project, as well as its adjacency to the borough’s diaspora communities.

Carl Gabriel in studio with Preston Community Library Commission, 2020. Courtesy the artist

The Biennial is a cultural assortment whose scope stretches far beyond making the best of a bad 2020. Its subtitle, On the Side of the Future, is inspired by cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s words when introducing his Kilburn Manifesto (2014), a bold intervention into post-neoliberal social theory: “We must stubbornly defend the principles on which the welfare state was founded—redistribution, egalitarianism, collective provision, democratic accountability and participation—and find new ways in which they can be institutionalised and expressed,” he wrote. The decision to use libraries to bring art to the community is, without doubt, in keeping with Hall’s vision.