This Artwork Changed My Life is a fortnightly series of personal essays that share the stories of life-changing encounters with art.

In 2017 I quit my job at a fashion magazine to, in short, decide what to do with my life. I’d been working in fashion magazines since before I left university, and by the latter half of my twenties I’d found that the deeper I got in the industry, the more boring and prescriptive I found it. It was all dresses and money, and I was tired.

I was not sure what I wanted to do next—maybe more journalism, maybe write a novel. Maybe retrain entirely, develop some practical skills. I thought that starting by going freelance might give me the time and space I needed to figure all of that out.

Twelve months later, the initial patina of freedom from the office had started to wear thin. For one thing, it wasn’t quite ‘freedom from the office’. I was now making my living working a series of short-term freelance contracts in ad agencies and for brands, and in between was writing articles on culture and books. The work was fine, sometimes fun, but it was work, regardless, and this was the inescapable truth that I’d managed to figure out: life, freelance or otherwise, was always going to consist of a series of agreements you make to sacrifice your time in exchange for some money.

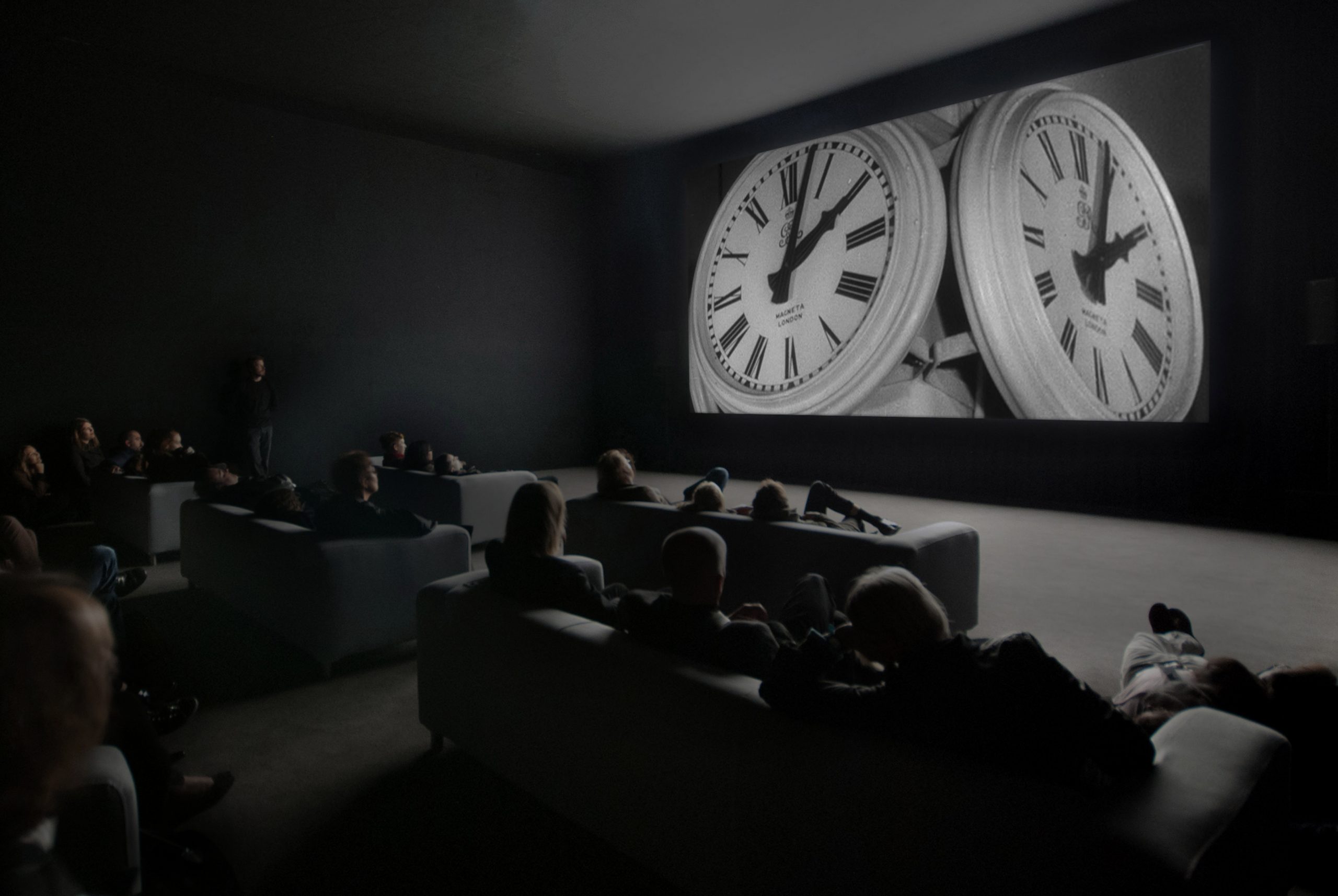

The location of my latest contract was a glossy, high-rise building near the Thames. It was autumn, and Christian Marclay’s film The Clock had just opened at Tate Modern. It was a piece of art I’d first heard about at university and had been fascinated by: a 24-hour-long video that stitches together clips from thousands of films in which clocks and watches feature. The result is that The Clock functions as an actual timepiece, in that viewers are watching an endless succession of images of the time at that very moment as it marches relentlessly on, in clip after clip from across the history of cinema.

One day, on my lunch break, I walked through Bankside and slipped into the Tate Modern’s Blatavnik Building. In a dark room upstairs, I took a seat and quietly pulled my packed lunch from my handbag. For 20 or 30 minutes, I watched The Clock. There is so much ticking on screen that it was impossible for me to forget about the other clock, the one that compelled me to go back to the office and earn my day rate. So after a little while, I stood up and headed back to the glass and metal building where the ad agency was located, and sat down to another afternoon of work.

“The Clock uses time in the way I do in my own life. Sometimes it is everything, and in other instances it ebbs away in the background”

At my desk I thought about what I’d seen. Time, I learned watching The Clock, is the container for everything in our lives. That’s why it can grate when I hand mine over to a company for a pay-cheque, paid by the hour and not by the word or the job.

In The Clock, time is incidental as much as it is crucial. For every scene of gripping tension, like the scene from The Thirty-Nine Steps (1978) where the protagonist clings to the hands of Big Ben, there is another scene where a clock just happens to be in the background while two characters converse or make love. Sometimes time is pivotal in these scenes: cowboys duelling at high noon, or lightning striking the clock tower at 10:04pm in Back to the Future. In others, the exact time itself is incidental. In this way, The Clock uses time in the way I do in my own life. Sometimes it is everything, and in other instances, such as at my desk at the ad agency, it ebbs away in the background without my noticing.

I kept going back to The Clock. I worked my way through Marclay’s day and some of his night. During my lunch breaks I managed to cover the whole run from 12pm to 2.30pm in small chunks. When I returned to the office, I opened my notepad and marked down the times I had seen. On a weekday off, I arrived when the gallery opens at 10am and stayed until high noon with a handful of clock-watchers: pensioners, students, tourists.

On a Saturday night, I queued with my friends and the rest of London for an all-night screening, drinking cans of beer while a DJ played LCD Soundsystem downstairs. We got in just before midnight and sit on the floor in the dark. We stayed until three in the morning. This, by the way, is a good section of The Clock, filled with dancefloors and lovemaking, crime, airports, nightclubs.

It is unbelievably difficult to watch The Clock and not try to put a narrative on the montage of scenes before you. As one sequence slips into another, I am left wondering what happened to the boy or the bank robbery in the previous clip. But Marclay’s narrative, if there is one, is about time itself, and in my own life I am also constantly trying to find through-lines, red threads that link the disparate events, chaos and nonsense I am always living through.

“I thought about what I’d seen. Time, I learned watching The Clock, is the container for everything in our lives”

I look for morals, lessons, closure, and routinely find nothing. I am still annoyed at friendships that fizzled out without fanfare years ago, or the toxic men I’ve worked with who never suffered any consequences for their actions. Right as some denouement seems to be coming, often I find that my life moves on to the next thing regardless.

Now it has been four years since I left my job to figure my life out. I have not retrained, or developed any new real-world skills. I started a novel the same autumn that I watched The Clock. It is long since finished and is now in a drawer. I still work freelance contracts in ad agencies. I have made my peace with the sale of my time for money. It’s fine, and it means I can live the kind of life I like, with some free time for my own art, if you can call it that. I will continue to work in this way.

I still look for the narrative in my life, even when I know it’s not there. But the story of any life, if there is one, is bigger than that. It is sprawling, boundless, incessant, like Marclay’s The Clock.