For Jo Spence, one of the sharpest ironies of the camera was how quickly it stopped telling the truth. By the early 1980s—when she was completing her undergraduate degree in photography at the Polytechnic of Central London—the medium was a mass art form, and cheap cameras were easily attainable. Yet for all its ubiquity, Spence felt the camera was failing in its duty to bear witness. The medium “has never been taken up by most non-professionals as a tool for showing other than idealised versions of everyday (and especially family) life”, she observed in 1982.

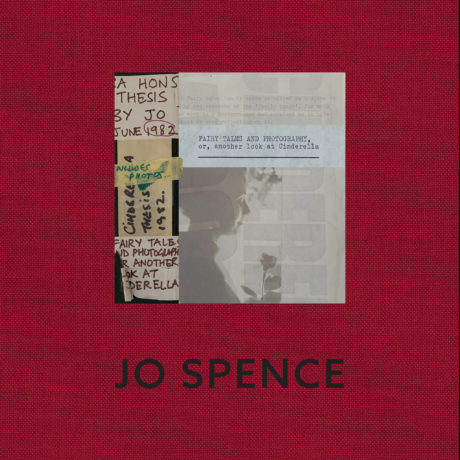

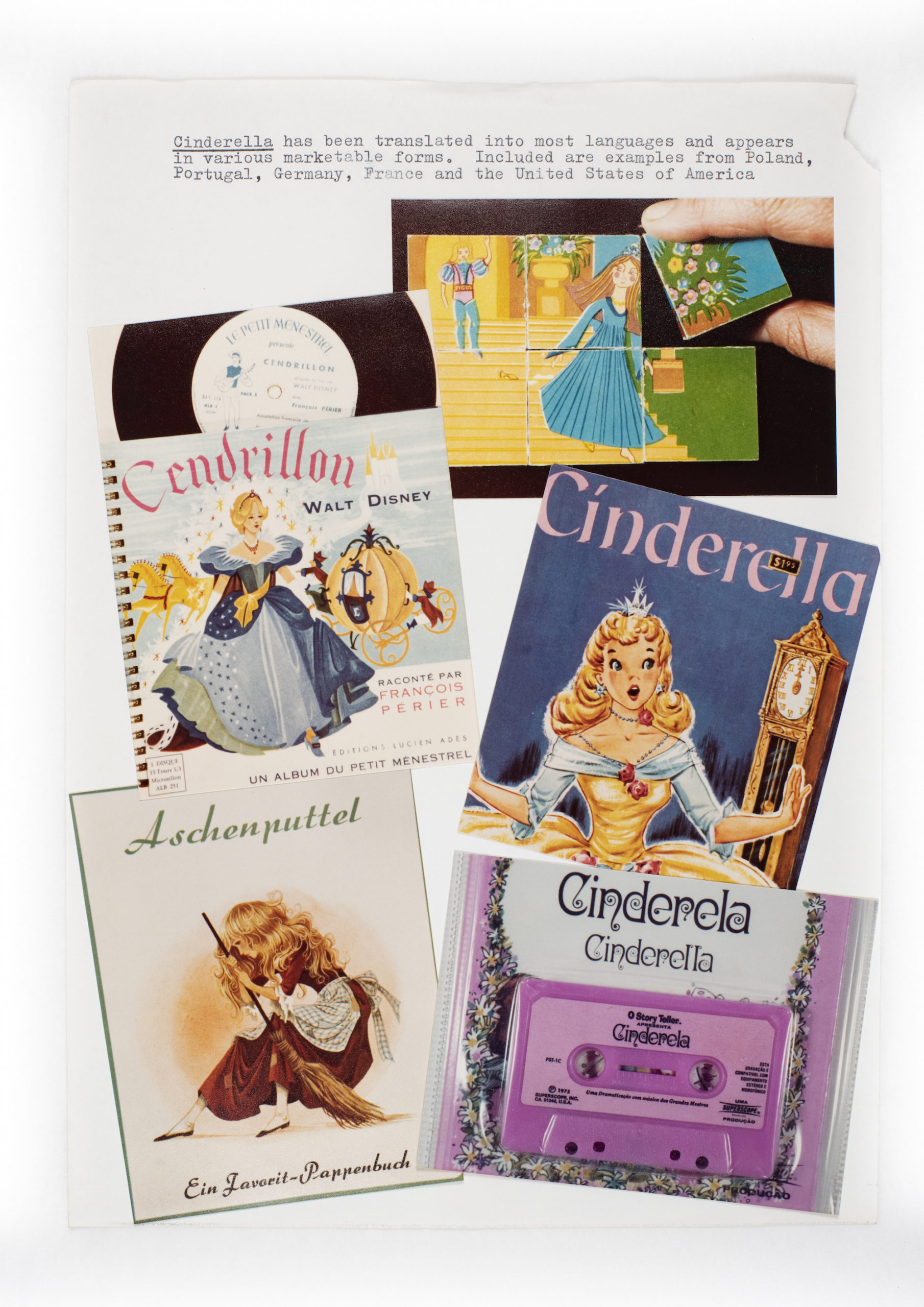

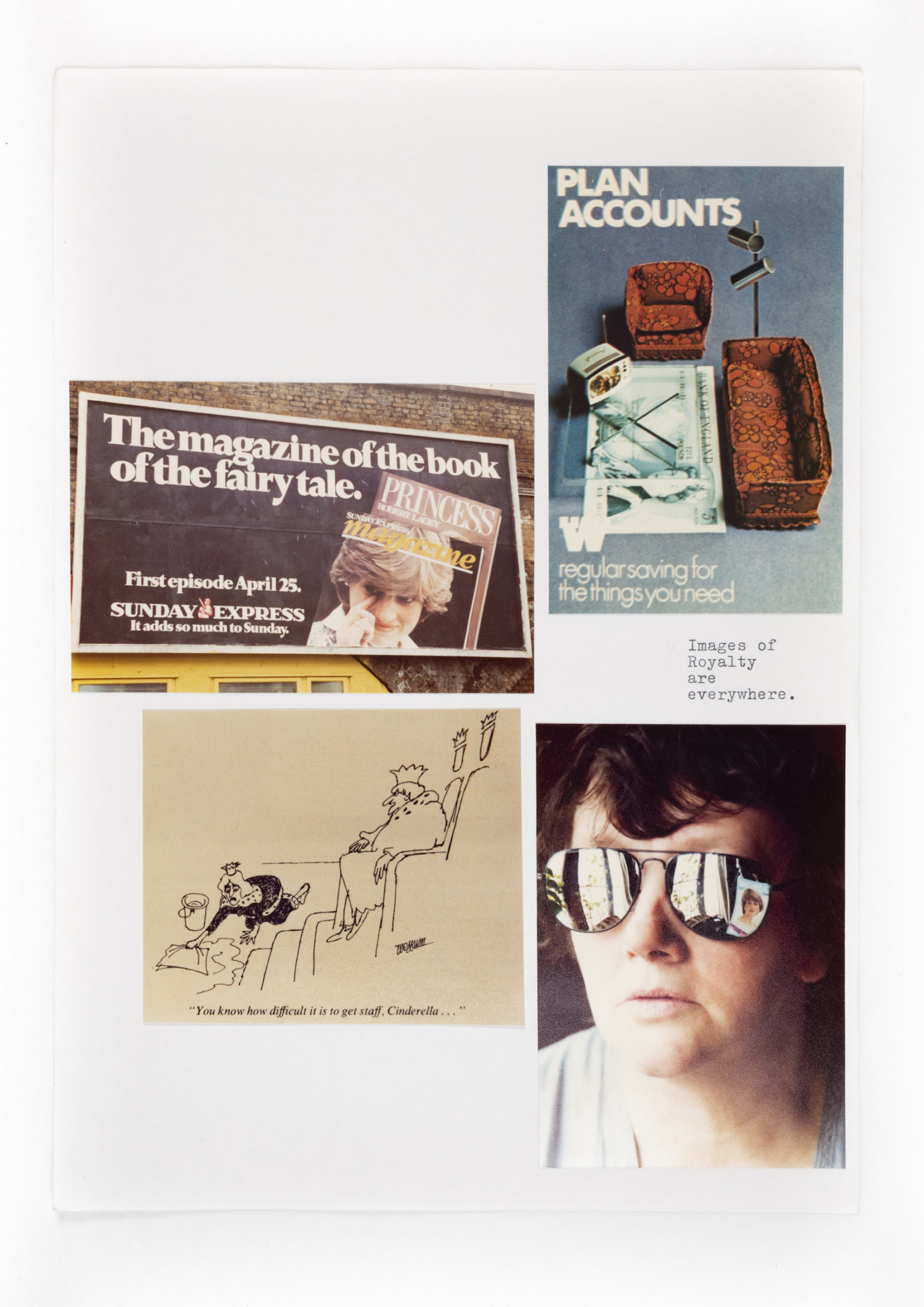

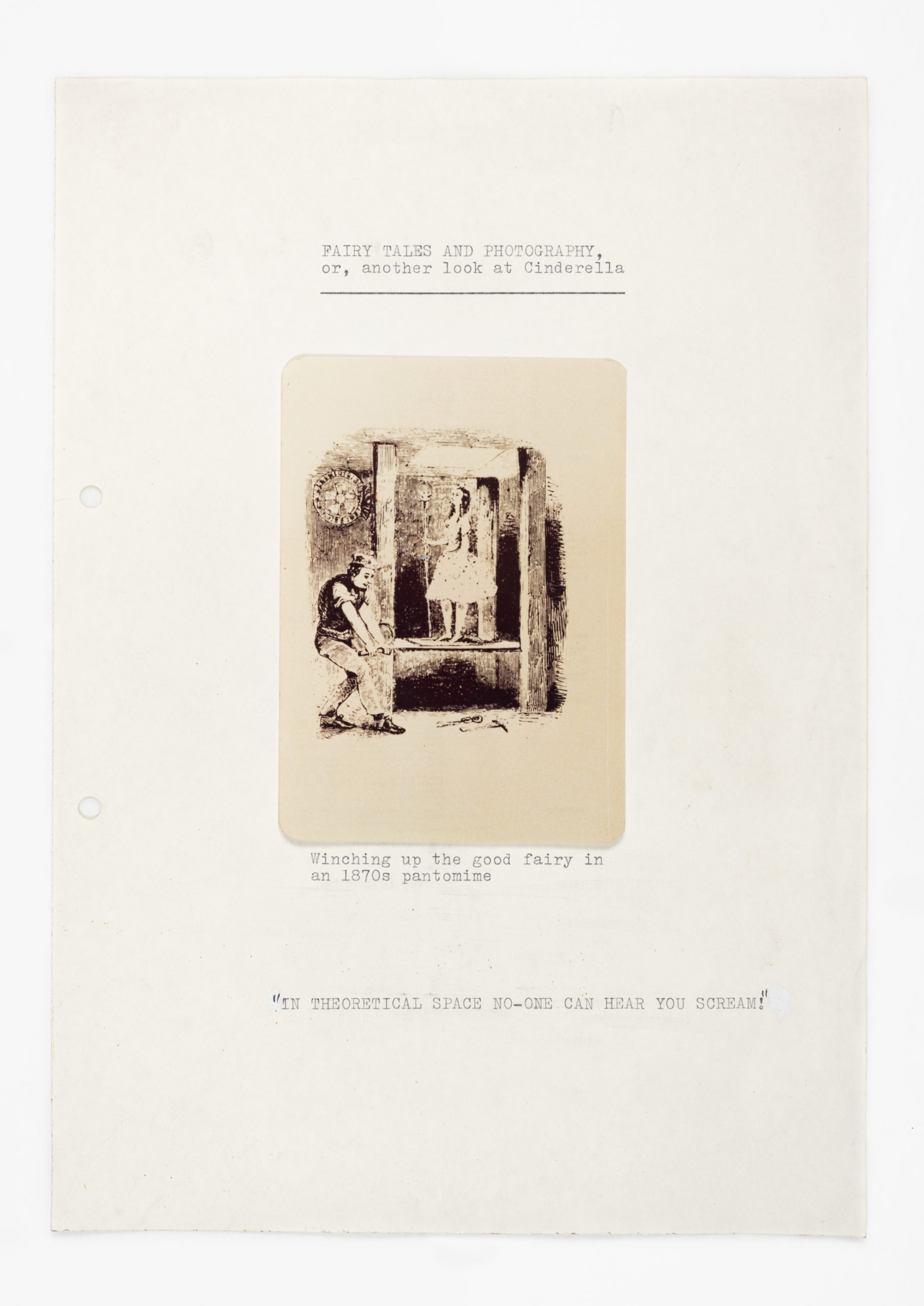

This assessment of photography’s shifting role in our daily lives come from her undergraduate dissertation, Fairy Tales and Photography, or, Another look at Cinderella, published in full for the first time in December 2020. In this landmark piece of writing, Spence dissects the currency of the Cinderella figure in mass media and advertising. The remarkable essay more closely resembles a doctoral thesis in its reach, taking in not only adverts but newspaper journalism, film, music, pantomime, opera, ballet and theatre—as if, in spotting a rotten apple, Spence discovers the whole barrel has gone bad.

“In a society at pains to hide its machinations, Spence holds back the curtain and lets us look right in”

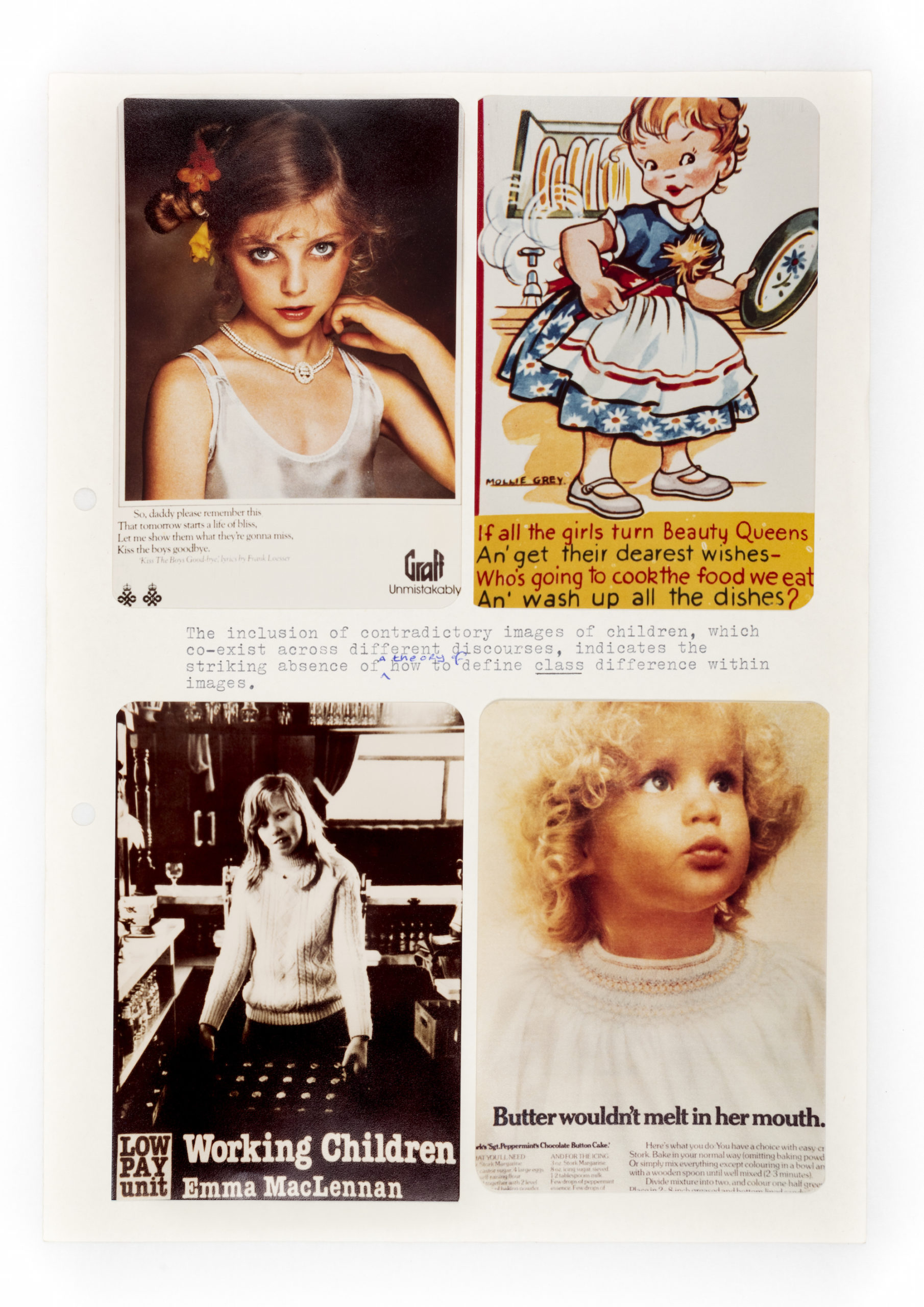

Spence was in her forties by the time she started her studies, a mature student who had worked as a high street studio photographer, capturing family groups and newlyweds, and as an artist and activist working as part of collaborative groups. As well as being working class and having never finished her secondary education (she left school aged 13 for secretarial college), this gave Spence a perspective shared by few others in the arts. And although she started the degree with enthusiasm, she was disillusioned with it on many fronts when the time came to write her final thesis. In an introduction addressing the tutors she felt had fallen short, Spence describes being baffled—angered even—by a set of theories so determined to treat “people as if they were ahistorically, universally gendered subjects”. “I’ll admit,” she goes on, “I wanted a theory that could take account of the construction of class difference.”

Earlier in the course, Spence had turned to fairytales “as a way of seeking a more utopian and fantastic future”. And yet even here, she explains, she could not escape. Reading Cinderella, she began to encounter the familiar dread she met elsewhere, and the fairytale princess therefore became a kind of mascot—an unlucky charm Spence finds everywhere. Even in work dating back to her time as a studio photographer, the princess-in-waiting is in evidence. Spence reproduces one of her earlier bridal portraits, a wistful young woman, eyes cast downwards, with a rose in her hand, and writes: “I have no explanation for how I came to be able to encode a photograph in this way.”

What troubles Spence most are the subjectivities the story delimits; Cinderella at odds with other (read: less attractive and/or youthful) women, and passive with regards to her own fate. The tale redeems her eventually—not thanks to her own faculties, but a heady mix of magic, marriage and material wealth. When you hold it up to the light, Spence argues, the story is just another suppressive tool of the ruling classes to make the forces structuring society appear unimpeachable. Photography becomes an arch enemy proliferating images of simpering, photogenic young women across our pages and on our screens.

Here, the thesis is tantalising in the clues it gives as to how Spence will go on to resist this unholy alliance. She starts as she intends to go on with her own text, drawing attention to the crossings-outs and Tipp-Exed corrections on the page. “Most dissertations I have read seem to deny their ‘marks of production’… those [students] that come after me… might be glad of evidence of the mental and manual toil, and stress, which preceded this essay,” she declares. A self-proclaimed “cultural worker”, she has no interest in artistry for its own sake.

“Spence describes being baffled by a set of theories so determined to treat ‘people as if they were ahistorically, universally gendered subjects’”

Throughout, admirers of Spence will glimpse her frank, raw, rough-edged approach: the hallmarks of her pioneering projects on trauma, illness and her body. And when her own artwork arrives, peppered through the book amidst the saccharine images of Cinderella, it is like a bracing breath of cool air. However tempting it might be, it would be superficial to suggest Spence was writing her own fairytale: although she graduated with a first class degree, she left feeling exhausted and confused. Instead, Spence offers something a little more unruly and open-ended; not “a thought”, as Elizabeth Bishop wrote, “but a mind thinking”. In a society so at pains to hide its machinations, Spence holds back the curtain and lets us look right in. She shows that stories aren’t the problem, if we only make sure they are better and more variously told.

Joe Spence: Fairy Tales and Photography, or, Another look at Cinderella

Out now, published by RRB Photobooks and The Hyman Collection

VISIT WEBSITE