“I learned I was colourblind at the age of fourteen”, says Loren Long, the award-winning American illustrator behind some of the world’s best-loved children’s books. During a regular screening for near-sightedness, Long was diagnosed with red-green colourblindness, a deficiency in perceiving colour that makes it difficult to distinguish between certain colours, in particular, blue, yellow, red and green. There are three types of colour deficiency, and they vary in severity: for red-green deficiency, red and green (and any colours that are made up of either), can both appear murky green. Colours can be confused and appear muted or dulled.

Colourblindness is linked to the X chromosome and therefore affects more men than women—eight per cent of the male population—one in twelve men—are colourblind. For women, the figure is one in two hundred. Despite the large number of people who are affected by colourblindness, it is rarely spoken about in public. However, with an increasing amount of information coded in colour, everyday tasks—from using a computer to navigating systems at work to choosing clothes and food—can become a relentless struggle.

Colourblind people can feel, “excluded from a world that’s so colourful and becoming even more so,” says Kathryn Albany-Ward, the founder of Colour Blind Awareness UK, an organisation providing information and insight into the challenges of being colourblind. Albany-Ward set up the organisation after her son was diagnosed with colourblindness aged seven.

There’s a certain stigma around being colourblind that stops many people speaking out about it —and, as many people who are colourblind are able to live completely normal lives, they prefer others not to know about the ways it affects them. One celebrity who has spoken publicly about colourblindness is Eddie Redmayne, who wrote 12,000 words on Yves Klein’s Blue while studying History of Art at Cambridge University.

“I only decided to share my colourblindness because I was exposed by my older brother during a Facebook live interview at the New York Times while promoting a book,” says Long. “He didn’t realize I didn’t want to talk about it and that I didn’t want people to know I was colourblind. I feared for years that it would hurt my chances of getting hired and I also just didn’t want to draw attention to myself. This is an annoying obstacle in my life—but others are dealing with real disabilities.” His publicist encouraged him that speaking out might help others who struggle with the same condition.

Art might not be an obvious choice for someone who is colourblind, but it doesn’t have to be a setback. It seems very likely that Van Gogh—celebrated for his revolutionary use of colour—could have in fact been colourblind. Albany-Ward points out that when looking at some of the artist’s most famous works through a simulator, they appear even more unexpected in contrasts. Constable is also thought to have been colourblind. The first diagnosis of colourblindness was in 1798, and many major works of art may have been created by colourblind artists.

“Colourblind people can feel excluded from a world that’s so colourful and becoming even more so”

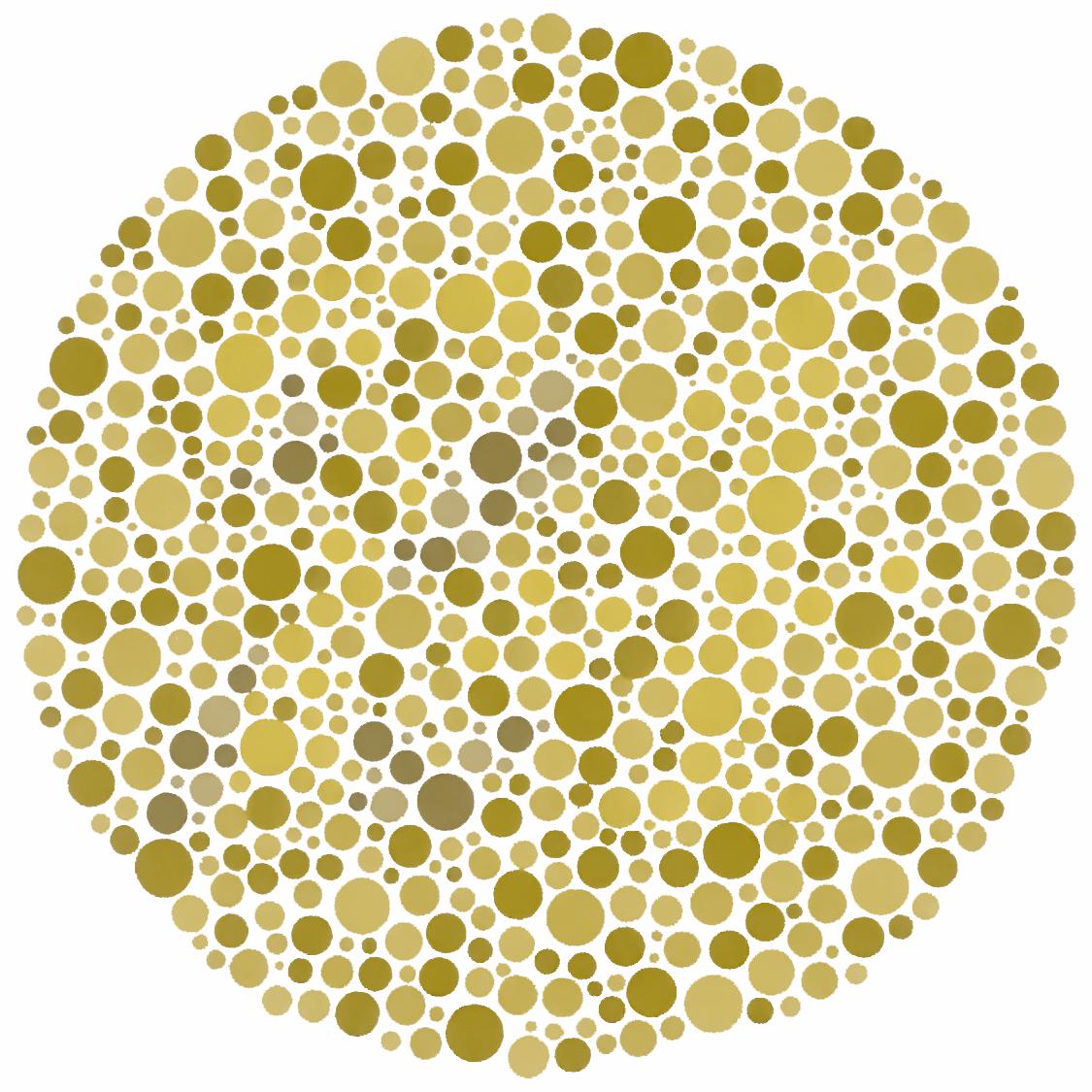

“Being colourblind hadn’t affected my career in design at all, until last year when in passing I mentioned it in a meeting where we were talking about accessibility and inclusive design. (Interestingly I’ve always been told I have a good eye for colour),” says Matt Roberts, lead digital designer at Sightsavers, who was diagnosed with red-green colourblindness via an Ishihara test, aged twelve.

Sightsavers is behind Perspectives—an initiative to promote equality, inclusivity and accessibility through design. They also produced a magazine with tips for graphic designers on how to make their work more inclusive, which has been shortlisted for Best Editorial Design at the Design Week Awards.

“Having spoken about it openly has given me opportunities to develop my career rather than hinder what I can and can’t do. Given how common colourblindness is, I was surprised to hear how few people knew about it,” Roberts explains in an email.

For Long, the experience was more difficult. “I was at the age where I had started to feel that art was my thing. I was a regular kid who liked sports and didn’t excel at school except in art.” Long recalls. “So it hit me hard when the optometrist told my mom that being colourblind was ‘relatively common, especially amongst males. It’s really not that big of a deal unless he wants to be an electrician, a dermatologist or… an artist.’ Hearing a doctor say I couldn’t do it was pretty devastating to me as a fragile fourteen-year-old.”

“Given how common colourblindness is, I was surprised to hear how few people knew about it”

Long—who can’t see the difference between purple and blue, brown and green or shades of grey—says that his colourblindness has affected his work as an artist since the beginning. “I can’t see the subtle hues that are in flesh tones like a John Singer Sargent. It means I can never paint portraits. I start with local colour and paint without worrying—I just do what I can and try to compose the best images I can to tell the stories in my books.”

The EU has guidelines in place for designing websites to enable colourblind people to access them—but for art, this would be impossible. How does art look to someone who is colourblind? What is the viewing experience like when you see differently to everyone else? “I think in art, in many ways, you’re less disabled as a colourblind person, because working in the arts is much freer,” Albany-Ward suggests. “You might notice shapes and imagery no one else would. I have normal vision, but I don’t understand art at all!”

- Left: John Constable, The Hay Wain. Right: The Hay Wain as it may look to a colourblind person

Roberts agrees. “Everyone is different. In the same way some people focus more on composition than content in a piece of art, people who are colourblind will notice different elements. Obviously, if the piece relies on colour, then it’ll be interpreted very differently. However, imagine the impact of viewing a Rothko or Constable in black-and-white. Does that change what you feel about it? Or is it still a block of colour and a landscape?” Colour vision simulators demonstrate to people with normal vision how significant the differences can be, and how vital the impact of colour is to understanding and ‘reading’ images in a full colour-oriented world.

“Make art that works for you and find an approach that suits you”

Despite being told he could never become an artist, Long, aged fifty-five, continues to create and invent ways to navigate his colour blindness. “My advice to young people who are colourblind and interested in a career in the creative industry is that there are so many creative directions one can go. Make art. Whatever kind it is, make art that works for you and find an approach that suits you. Ask for help. Ask for help from friends, family, coworkers and even strangers. My wife checks every painting I do while I’m working on them and before they leave my studio.”

For Roberts, the issue goes further and wider. If we can understand how our experience of the world is affected by the way we see it, we can begin to build a more connected society in which everyone is able to engage and take part in it. “I think more can be done about raising awareness of colourblindness, but I think it’s also important to take the opportunity to talk about other common conditions that can affect people and their ability to engage with art and design, such as dyslexia, autism, hearing loss and visual impairments.”