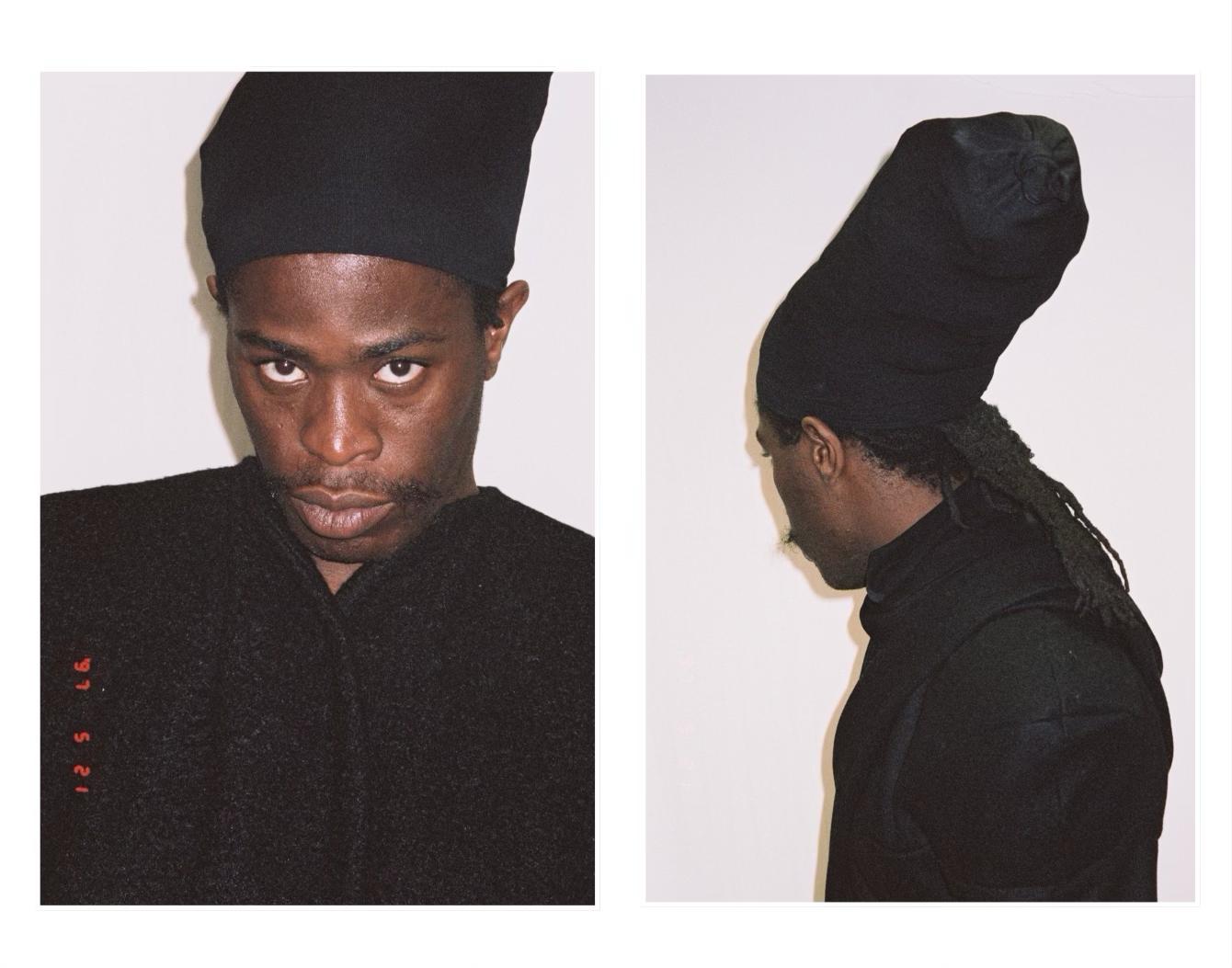

London- Emmanuel Shogbolu is on a mission to keep his culture alive by tracing his influences and memorialising them in his art. Born and raised in East London, the multidisciplinary artist and researcher documents hyper-locality spanning generations and continents. His sprawling practice includes filmmaking, painting, photography, sculpture, music and assemblage.

So far, the artist has turned his lens towards his own adolescence in Warrior Square, an estate in Newham; the legendary UK Grime and Road Rap scenes (and the filmmakers who documented them); Afro-Caribbean youth culture in London in the noughties to mid 2010s; and contemporary African diasporic subcultures all over the world. His love for music reverberates in the cadence of his editing, the countless rappers he lifts from obscurity, and soundscapes that oscillate between soulful and frenetic.

Shogbolu’s expansive archive of found video footage is central to his work, which captures his unique personal philosophy of seeing, thinking and being. “My name is Emmanuel Shogbolu, but everyone calls me Scatty,” he tells me, adding that the name was initially given to him jokingly by a childhood friend. “In UK slang, ‘scatty’ means messy, unorganised or to simply not give a heck. I tried to find a balance, some sort of positive ground within that name,” he says. Now, he finds power in the sporadic nature of the word. “To me it means freedom, to embrace opposing spectrums and some sort of positive ground within that.”

“My way of seeing the world is kind of all over the place, but when it comes together, it says something about the beauty within chaos,” he explains.

Scenes from Shogbolu’s film Pieces of a SCATTSMAN (2023) are now on view until July 21st at the Austrian Cultural Forum in a group show, “Disagreements,” curated by Nimco Kulimye Hussein. Next month, he plans to screen his film SCATTSMAN (2022) on August 9th at Cafe Oto alongside new video and sound work under the alias SCATTSMAN.

Shogbolu, who graduated from the University of Southampton in 2013 with a degree in cultural journalism, started making art three years ago after he began going down rabbit holes on Youtube on a quest to better understand himself. To this day, he shares the footage he finds on his Instagram account, SCATTSMAN. “I wanted to figure out what’s unique to the environment where I grew up in contrast to the rest of the world,” he says of his approach to his never ending anthropological project. “I started analysing the way we walk, talk, the subject matters within our music, our ways of dressing, the experience of being first generation African but also British here compared to the Black/American experience.”

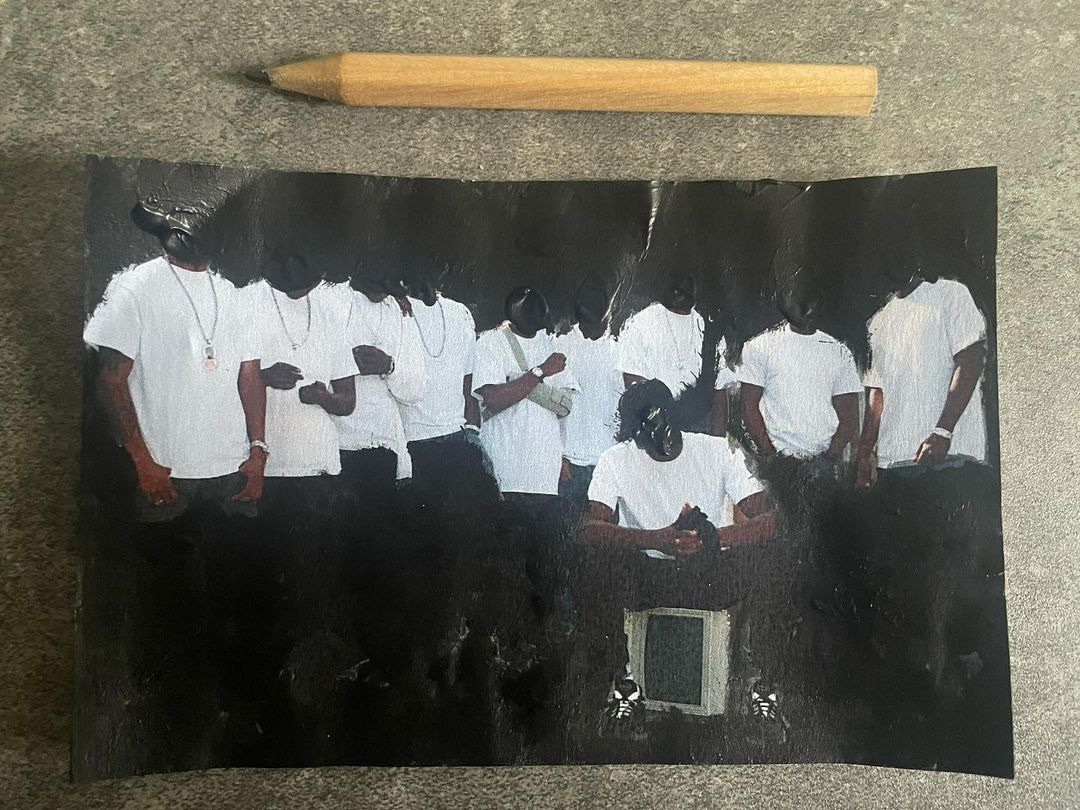

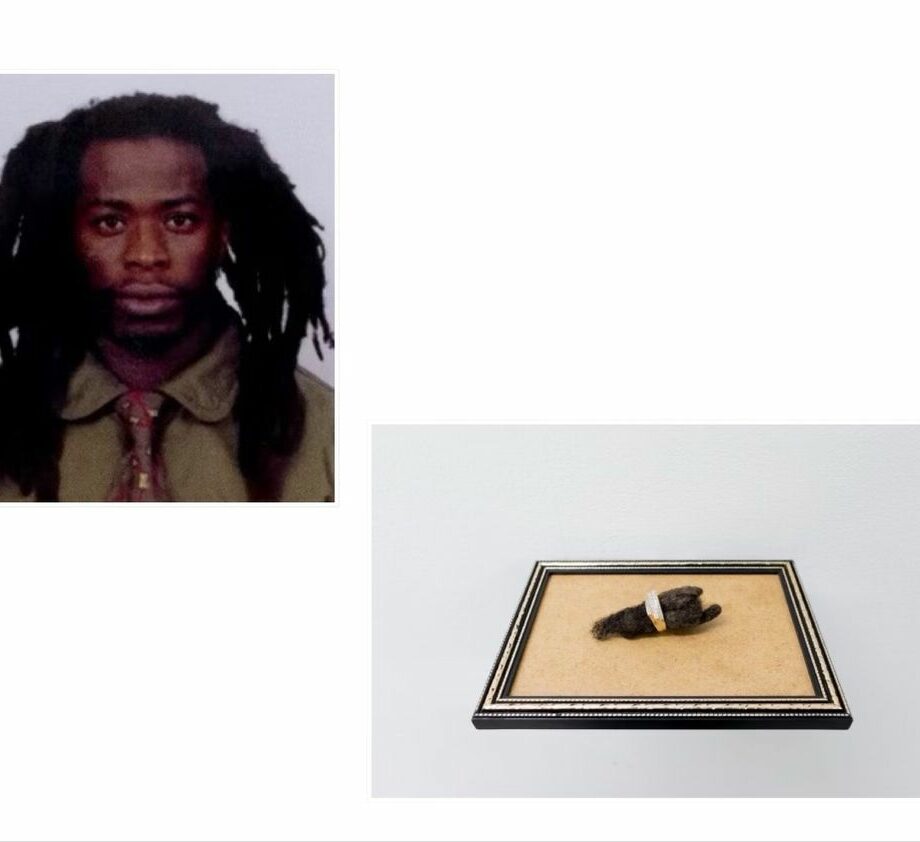

6×4 photograph with acrylic ink on found photo frame. Photo Credit: Harlesden High Street Gallery

The artist does most of his research on his phone. Throughout his work, Shogbolu has probed the question of self-representation and the cultural signifiers that he observed as a teenager in the early to mid 2000s.

“How can I take a self-portrait without actually showing myself?” he asks as we scroll through his Instagram. He lands on a still from a homemade music video that made its way from a DVD to Youtube: A grainy shot of two young teenagers looking over from in front of a brick wall; a long dark shadow cuts a triangle in the green grass at their feet, hinting at a towering building out of the frame. “It could be me and a friend; it could be anyone within that picture,” he muses before continuing to an image taken from a video from 2012.

Here, the boxer Richard Riakporhe formerly known as Blacks is suspended mid-jump, floating above a basketball court in Aylesbury Estate. “He was actually in a gang and a rap group at the same time as he was training as a boxer. Eventually, he made it. He’s doing really well,” he tells me.

The pre-fame image is part of the boxer’s life story; his perfect posture and toned body hint at the determined discipline of a star already beginning to rise. Shogbolu sees this echoed in the shadow of the rim underneath him: it represents “transcending what you are a part of, what you thought you knew, and taking it to another level,” he gestures towards the abstract, dark area. “And that’s just one picture.”

For the artist, every picture represents a bigger story. “I’m not taking credit for all the work,” Shogbolu clarifies, “but when I take the screenshot, it makes a camera sound, and it feels like I was there. I’m still in the area where I grew up, so I can walk past certain spots and remember those moments.”

In SCATTERATION 1.0 (which Shogbolu debuted last year in a group show curated by Infinite Fx for the Institute of Contemporary Arts), a poignant scene depicts cops harassing a group of teenagers playing on dirtbikes. A man urges the police to put down their guns. Another young man begins rapping on the spot; the cops circle behind him, as he outlines the dual ridiculousness and seriousness of racial profiling. Here, the filmer takes on the role of a protector, documenting the ever-present threat of violence at the hands of the same systems that his community should be able to depend upon.

“I am my brother’s keeper,” a man raps to the camera in the first few moments of LDN 2 NYC (made the following year). “Here are the people inspiring me to do what I do, the people that were documenting the moment,” Shogbolu narrates as we watch the film, which begins with a man in a wheelchair making a case for the London rap scene. Through his research, Shogbolu learnt that the man in this footage is the same person who produced many of the videos he used in LDN 2 NYC. “Where is he now? Is he okay? Is he still making films? Does he know how much he influenced me and others alike?” wonders Shogbolu, who sometimes catches glimpses of old faces from the footage in his tight-knit, working-class East London neighbourhood.

Growing up, the artist would watch rap videos in after-school clubs in the youth centre, research in the library, listen to music with his friends, and later, go to museums and galleries to learn about art and study world history. He observes that as a child, the colonial pressure to assimilate materialised in adopting an extensive vocabulary and intricate wordplay. “My family is from Nigeria, and in my household, there was a pressure to fit in, to be more English than the English. For example, my dad drinks more tea than an Englishman,” he laughs. “Growing up, there were loads of words used in my household that I would use in school, and they were surprised that I knew them.”

Shogbolu traces this same desire to excel in (and subvert) the English language to the London rap scene, specifically Road Rap, the descendent of Grime. “With Road Rap, the lyrics tell stories. They are poetic. It is our equivalent of the blues or folk music,” he says.

In the past two years, Shogbolu has built momentum with three films that draw from his video collection — SCATTERATION 1.0 (2022), Pieces of a SCATTSMAN (2023), and LDN 2 NYC: 2003 – 2013 (2023). Pieces of a SCATTSMAN begins with a scene of two young men fighting. At first, it seems as though it may well be a real fight, yet as the film continues, it becomes clear that they are play-fighting, underscored by the faint audio of the men laughing. This opening introduces the tone of subversion, which prevails throughout.

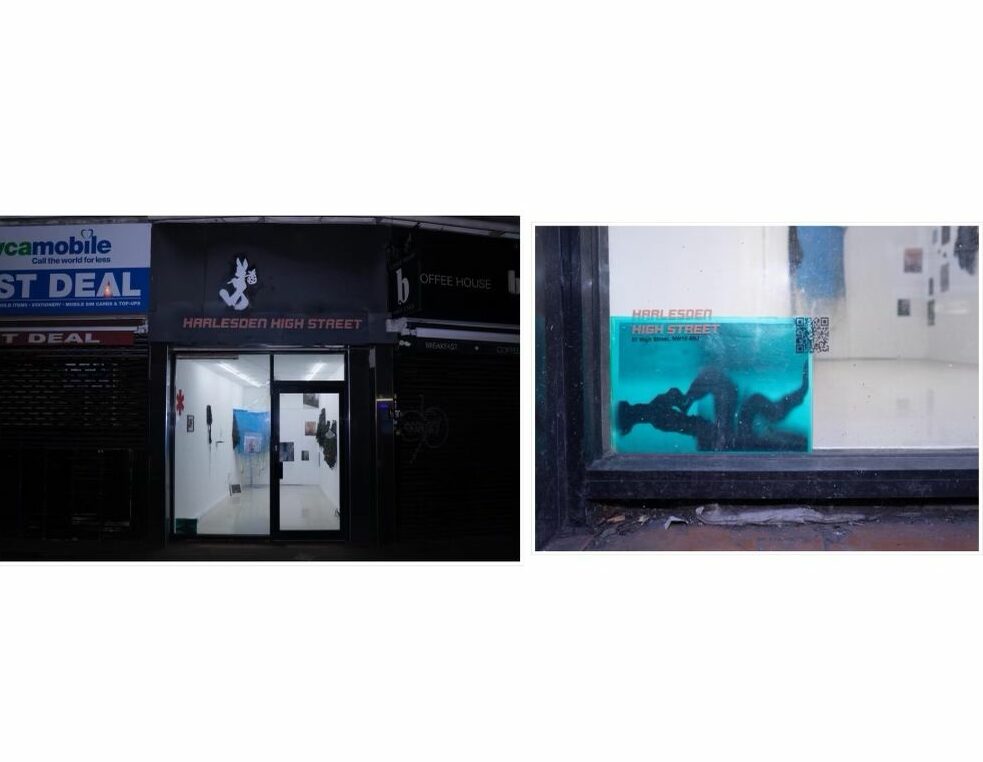

Last January, Shogbolu presented Pieces of a SCATTSMAN for the first time at his debut solo exhibition at Harlesden High Street Gallery, a small space attached to a bakery on High Street in Harlesden with a community-centric program and a dedication to platforming underrepresented voices in the arts.

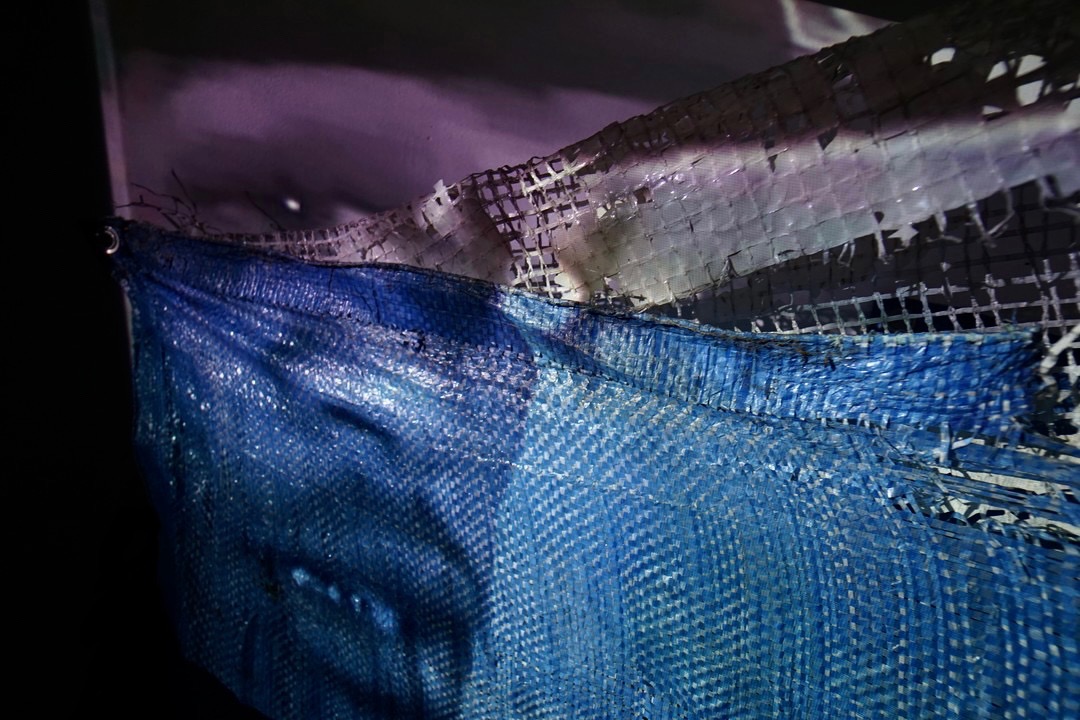

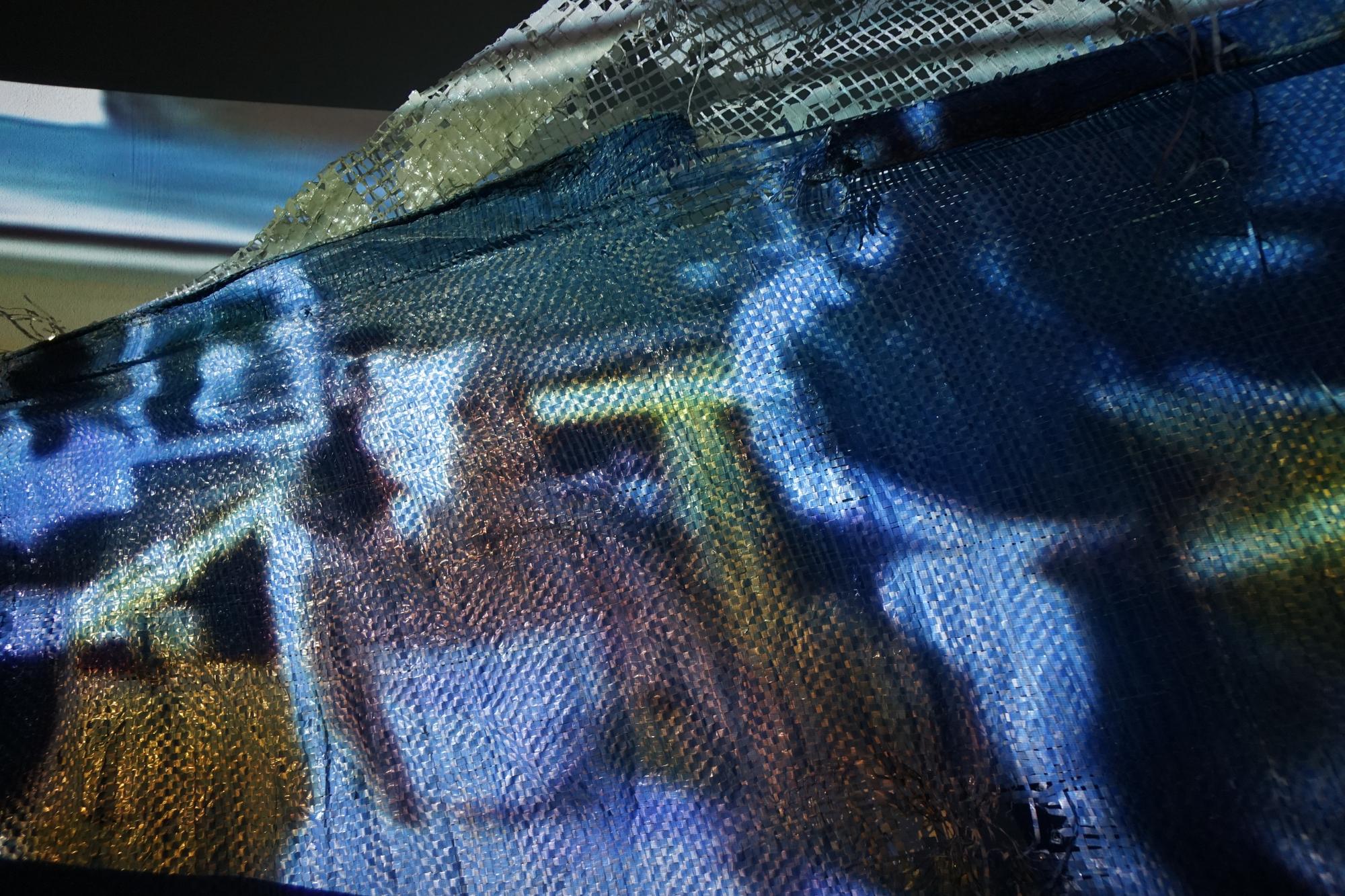

Shogbolu’s immersive exhibition at the gallery presented a visual history of the world that raised him: autobiographical ephemera, sculptures made from his own locs, paintings, assemblages and photographs taken by the artist as a teenager taped to the walls. His film was projected onto a tattered tarp-turned-tapestry seemingly taken from a construction site, accompanied by photos of his friends, which sat alongside old found photos of locals; its audio pulsed through the show. Fragmented verses from rap songs met insightful commentary, which paid homage to the poetic lyricism and astute observations of rappers and filmmakers of the mid-2000s, stemming from London and neighbouring cities like Birmingham and Manchester.

“He is digging up cultural references that are very obscure and have no sort of record or documentation. This is underground stuff, and as time goes on, it will fade away, but he’s building this really strong archive,” says says Jonny Tanna, the founder and director of Harlesden High Street. “This is something that we’re trying to do at Harlesden — create a place for contemporary history to provide people with an insight into the stories that will slowly get lost to time if we don’t do something.”

Tanna met Shogbolu after Joe Bobowicz from Ridley Road Project Space brought the artist into the gallery for an introduction. Shogbolu showed Tanna his archive on his phone, and the seeds of the eventual exhibition and film Pieces of a SCATTSMAN were planted.

“In Harlesden, we are a Black neighbourhood; there isn’t an art scene; there are no art schools; there are no galleries. We’re literally the only gallery around here,” says Tanna who grew up in the area and still calls it home. “Our goal with the gallery was to change the idea of what community art is and to make it accessible for visitors, but also for artists who might want to show with us.” Since moving to his current location in 2020, Tanna has met numerous local artists whom he may well have never encountered had he not found a space in Harlesden. “It’s really heartwarming,” he says. “I really want more people to be aware, not about us in particular, but about the people that we are working with.”

For his second exhibition with Harlesden High Street for the gallery’s booth at New York’s Independent Art Fair, Shogbolu made a video that zeroed in on the cultural exchange between New York and London via the New York Yankee hat. The hat is many things for the artist: a memory of his adolescence (an early photo of himself in the cap sparked the inquiry), commentary on the cultural exchange between the London and New York music scenes, and an emblem of aspirations of the “American dream” as personified by artists like 50 cent and Jay Z, who once rapped “I made the Yankee hat more famous than a Yankee can.” Now, Shogbolu says, the times have changed as American rappers look to UK rappers for inspiration.

The hat also underscores class and race tensions in London and beyond, representing, as Shogbolu explains, “the limiting stereotypes of what Black people can aspire to be.” This sentiment alludes to the oppressive misconception that to succeed in the Black community requires becoming a professional athlete, rapper or criminal.

While his practice extends in countless directions, it is grounded in the conceptual. His work recalls that of visionary filmmakers Kahlil Joseph and Arthur Jafa, who utilise media footage and archival clips as a means to create meaningful narratives that challenge misconceptions of Black life.

For Shogbolu, art is a means to an end. His aim is to ultimately develop a new, transcendent way of thinking. He is inspired by cultural thinkers like Stuart Hall, a Jamaican-British cultural theorist who studied representation in the media, and the radical teachings of Clarence 13X, a religious leader and the founder of the Five-Percent Nation- a Black nationalist movement. “The academic language is kind of off-putting, but through music, sound, and imagery, it can become a lot more accessible to everybody,” he explains. “Part of my job is to make these ideas more digestible.”

The artist sees his project of documenting the world he grew up in as “bigger than race, and bigger than street culture. It returns to our African and Caribbean roots, colonialism, and English literature. It is bigger than style: it’s scatty in nature. It means freedom, really,” he emphasises. “That’s what I want my work to explore: freedom through knowledge.” As Shogbolu outlines future plans for a book, paintings, music, curation and more films, it becomes clear that the artist is just getting started.

Words by Meka Boyle