This Artwork Changed My Life is a fortnightly series of personal essays that share the stories of life-changing encounters with art.

I grew up in photographs. A photograph was a bright and vivid proof of life as it is lived, all colour and movement, glued into family albums. Photography was also the work of my artist mother. For her, I lay on the floor twisted in fairy lights with my brother and sister for a Christmas card picture, and later I lay on the roots of a bleached tree for an art photograph. I didn’t mind, I was a child taking instruction.

Then one day I did mind, and stopped cooperating. I don’t remember this decision, but my refusal is visible in my disappearance from the albums. Just as I’m leaving childhood, I become the back of a head, or occasionally a face contorted in rage that I’m there in the picture for a moment again.

Later, I started taking pictures myself. Perhaps it was a way of exerting control, putting myself safely on the other side of the lens. At the time, though, it didn’t feel like that. I was drawn to image-making, but it wasn’t an impulse I thought hard about. As a teenager studying literature, my sense of photography was as a comparatively blunt instrument, recording only the outer surfaces of things where books could describe the interior.

“It’s a self-portrait, but it’s also a self-effacement, a complication of the self, rather than a capturing of something essential”

At best, a photographic portrait might show the crudest facts of a person’s split-second experience (grief, pride, longing) but where was the nuance, the temporal? How could the outward appearance of a person or situation get at the heart, the mind, the relentlessness of change?

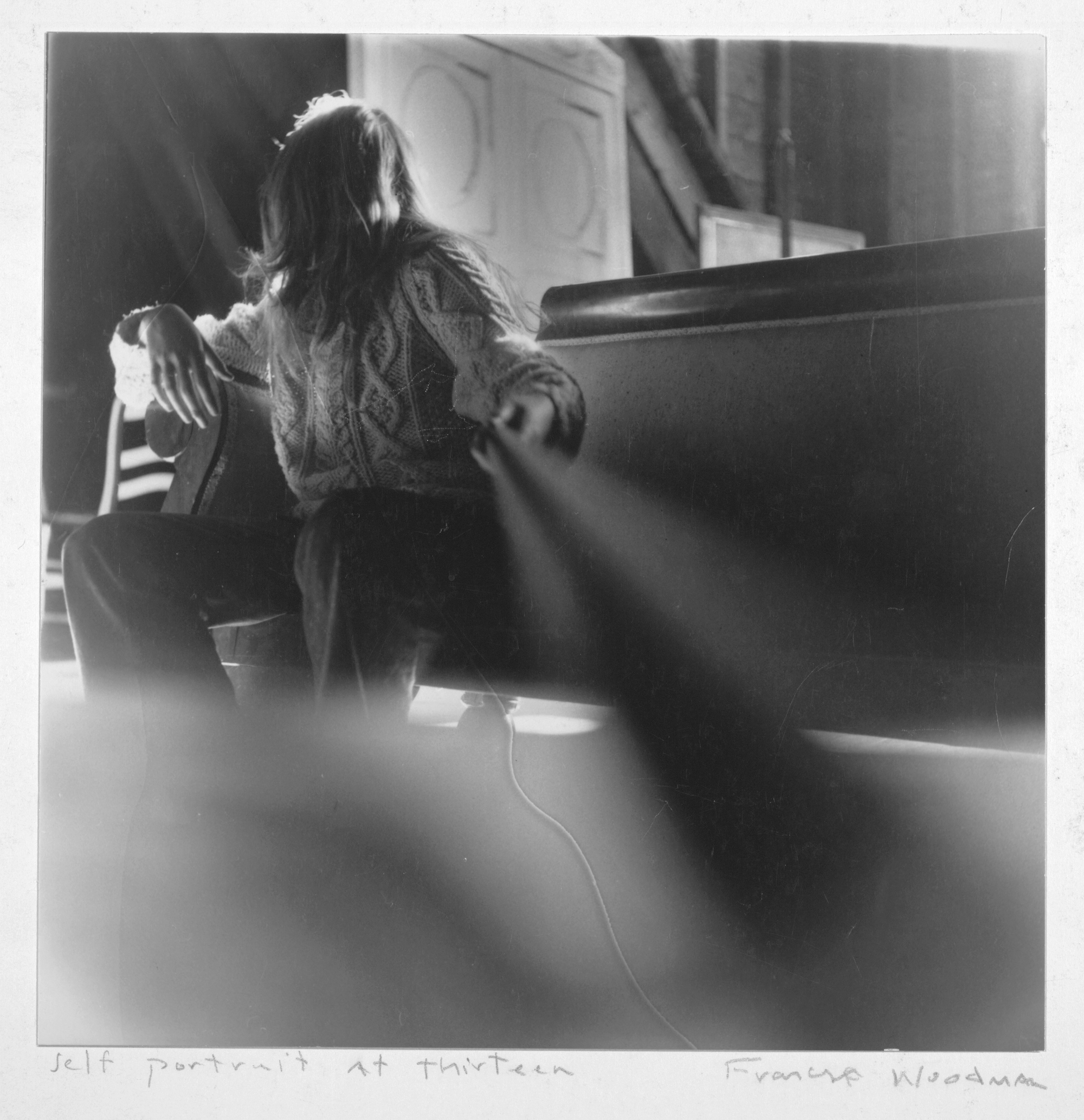

That winter my assumptions were upended when I met a friend at Victoria Miro gallery in London on a cold white day. It was here that I saw Francesca Woodman’s work for the first time as I stepped quietly around the gallery. The prints were small and intense in their velvet greys, and showed figures and forms twisting and elided by long exposure, hidden or distorted by wallpaper and clothes pegs.

In Self Portrait At Thirteen, Woodman uses herself in the frame, but she is turned away from the camera. Her body is a kind of graphic element, just as much as the cable from the shutter release. Light frames the back of her head, forms a delicate halo around her exquisitely relaxed hand. It’s a self-portrait, but in her turning away it’s also a self-effacement, a complication of the self, rather than a capturing of something essential.

“Woodman showed me that refusal and disappearance could be the subject of the work, an image could be both things at once”

Looking back at the moment when I saw that image for the first time, I think of my own refusal, my own turning away from the camera at a similar age. Self Portrait At Thirteen countered my belief that you could either turn towards or away from images. Woodman showed me that refusal and disappearance could be the subject of the work, an image could be both things at once. As I pursued photography more seriously in the years that followed, I began to wonder what else it could do.

Woodman’s work opens up a space that words can’t access, using the symbols of myth or religion to provoke questions, or induce a restless kind of feeling that can’t be easily described. It reminds me what visual art is capable of more generally, articulating something beyond words. As a teenager this felt revelatory. I had a new sense of the possibilities of photography, the ways it might broaden rather than foreclose the scope of our feeling.

“I had a new sense of the possibilities of photography, the ways it might broaden rather than foreclose the scope of our feeling”

In the decade since I first saw it, that photograph has continued to exert a subtle influence on both my thinking and my practice. I have started to step cautiously into my personal work, seeing the self as a formal material that can be explored or challenged on the photographic plane. A few years ago, I photographed throughout a phase of personal upheaval, eventually making a project about archives and memory, cringing at the self-exposure and vulnerability it required. When I returned to look at it later, it felt both completely entwined with and completely separate from me.

Last spring I collaborated with another photographer on a series of self-portraits. When the rolls of film came back, I was amazed to find that they seemed to know things that we didn’t, standing there in the pictures with the dawn light on our backs. The figure I saw in the images felt not like myself, but like a symbol. The photographs were the record of a performance whose own logic I had not understood as I was enacting it. Such is the potency of the photographic scenario. Woodman demonstrated the camera’s capacity for the uncanny.

In her final diary entry before her death in 1981, Woodman wrote that she was “inventing a language”. If photography previously felt to me like a proof, here is a work that proves other worlds can be created with all the strangeness of fiction. This is one of the reasons that biographical readings of her work, which focus on her depression and eventual suicide, are so frustrating. Rather than offering clues as to the meaning of her photographs, she believed that her death would leave her work “intact”.

“A medium that seems, on its surface, to depict reality is also ideal for antagonising that relationship”

As a reader, I am drawn to the push and pull of reality and fiction, towards and away from one another. In the decade since I discovered Woodman’s work, my inclination in photography echoes that push and pull. A medium that seems, on its surface, to depict reality is also ideal for antagonising that relationship. A picture that uses the self and yet conceals it carries the same tension at its core.

Loving Francesca Woodman is not unusual now: her work has been picked over, analysed, lauded and dismissed. But Self Portrait At Thirteen was my first encounter with a photograph that played at the borders of fiction and fact. I see its influence in all the images I’ve been most drawn to since, and in the photographic works I am tentatively beginning to make. My relationship to it, and to her, is ongoing.

Alice Zoo is a photographer and writer based in London. Her work has been commissioned by publications including BBC News, The New Yorker, and National Geographic