New York- Hamzat Raheem is a sculptor on a mission to collect 1,000 faces. The end goal is a sum of its parts: Stone with 1,000 Faces, an immersive, monumental sculpture carved on the interior of a cave (likely an abandoned marble quarry on the East Coast).

The project began in 2021 as the artist set out to understand the act of collecting after an early contentious experience selling a stone carving of his own face to a collector. “In order to make that sculpture, my face had to be collected,” says Raheem, setting the premise for a life-long inquiry into the act of collecting. “I thought, what does it mean now that he owns my self-portrait?”

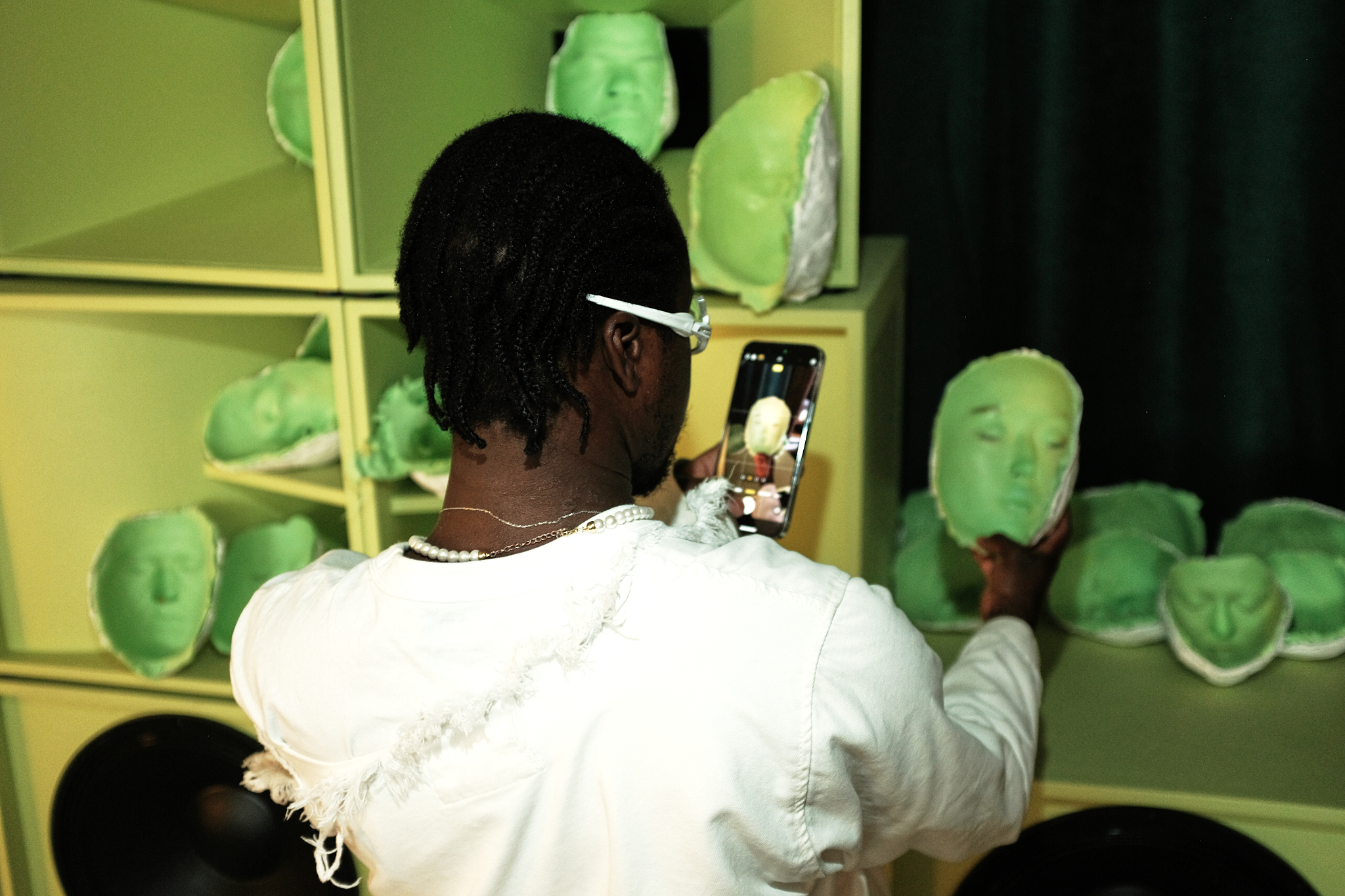

At first, Raheem’s face-collecting project grew slowly — the artist began making molds from the faces of loved ones — then, it picked up momentum a year in. So far, he has collected 156 faces and counting; a large number were collected in mid-May during a pop-up in New York City.

The 27-year-old sculptor collects out of his home studio in Massachusetts, his backyard, in New York startups, hotel rooms, and various locations across the country from Detroit to Miami to Los Angeles. Soon, he hopes to return home to Nigeria and collect the faces of the rest of his family. Whenever he travels, he carries his mold-making materials with him.

Raheem has made molds of the faces of his mother and father, his brother, childhood friends, artist peers, strangers-turned-collaborators from the internet, and a slew of New York City creatives and personalities such as the model Paloma Elsesser, musician the Dare, Drunken Canal and Byline Co-Founder Gutes Guterman, and socialite-turned-infamous-scammer Anna Delvey.

The artist underscores that he wants to collect everyone’s faces regardless of who they are. “One of the most recurring things that I’ve noticed has been people asking if their face is good enough or pretty enough, but that is the last thing that I’m thinking about,” he says. “I’m actually thinking: Are we in the same location? Do you have time when I have time, and are you willing to sit down for 45 minutes?”

The project is the antithesis to Dunbar’s number, the notion that humans can have no more than 150 meaningful relationships. Raheem probes at the underlying capacity for human connection that seemingly has no end in the digital age. “I think about the artist and a network environment, meaning the internet, which can connect way more than 150 people, more than a thousand,” he says. “Conceptually, that’s where that number 1,000 is grounded.”

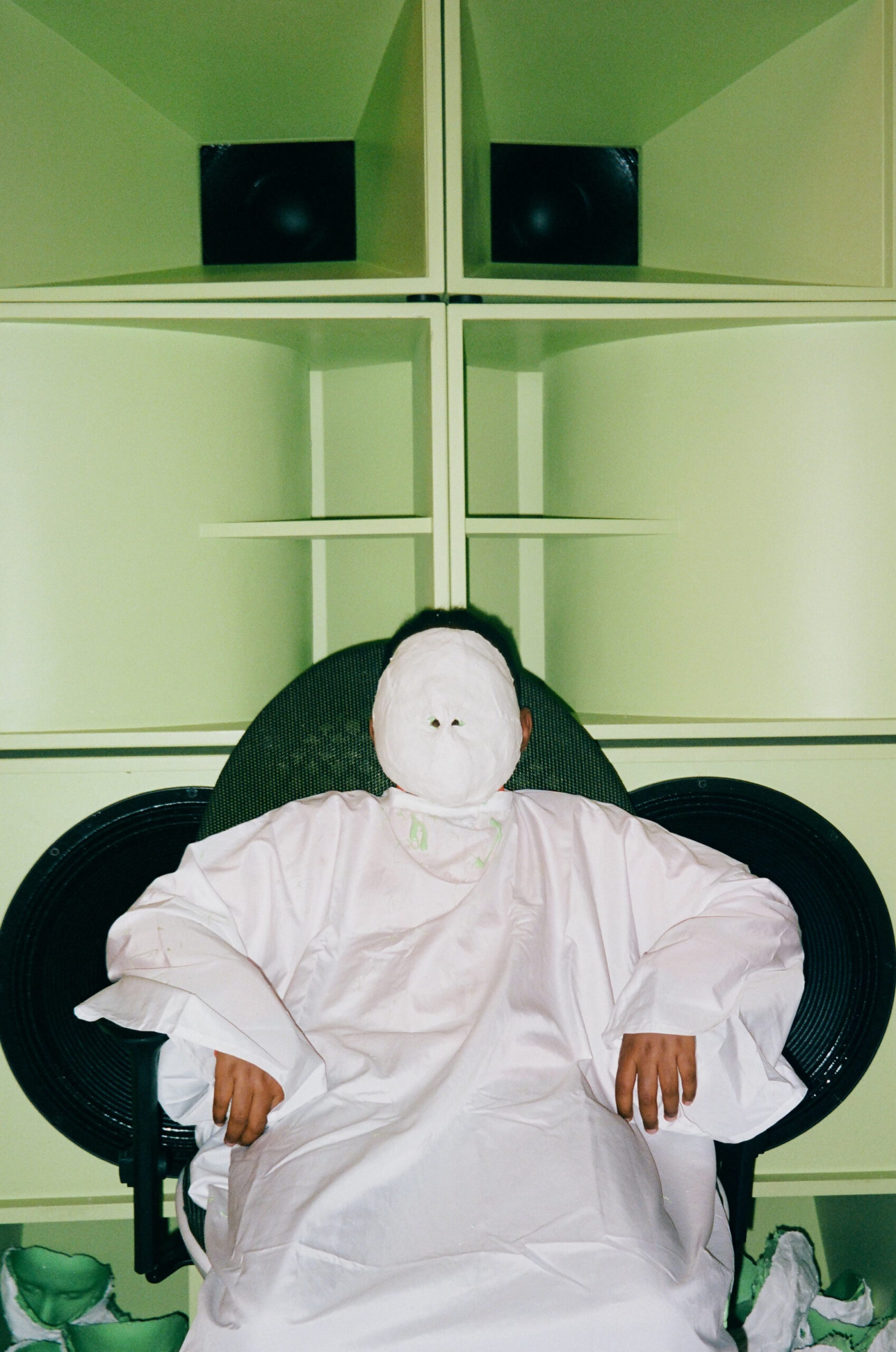

Yet, for Raheem, the individuals cast in a silicone mold are more than faces: each sitter offers a new moment of connection as the artist gently uses his hands, wet with white plaster, to mold rectangles of gauze to their cheekbones, their mouths, their noses, until their entire face is concealed. Face to face, in silence for close to an hour, one can’t help but think of performance artists of the past who grounded their work in endurance. In Marina Abramovic’s seminal act, “The Artist Is Present,” the artist sat across from viewers in a heavy, moving silence. Here, in Raheem’s hands, the viewers become collaborators: eyes closed and silent, they often refer to the experience as a moment of introspection. Some enter a meditative trance. Some fall asleep. The day I was there, a mother was moved to tears afterwards as she held the molds of her and son’s faces in her hands.

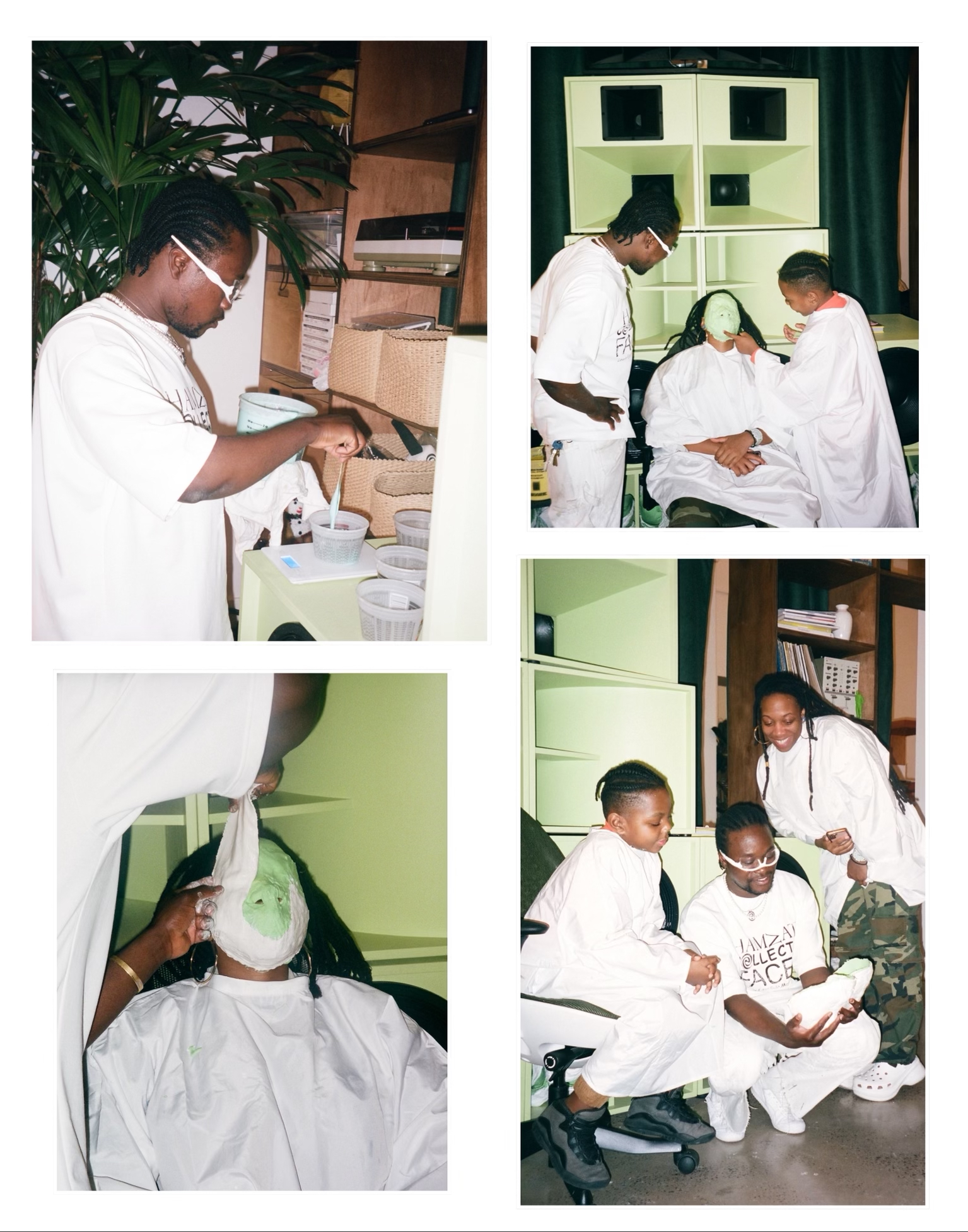

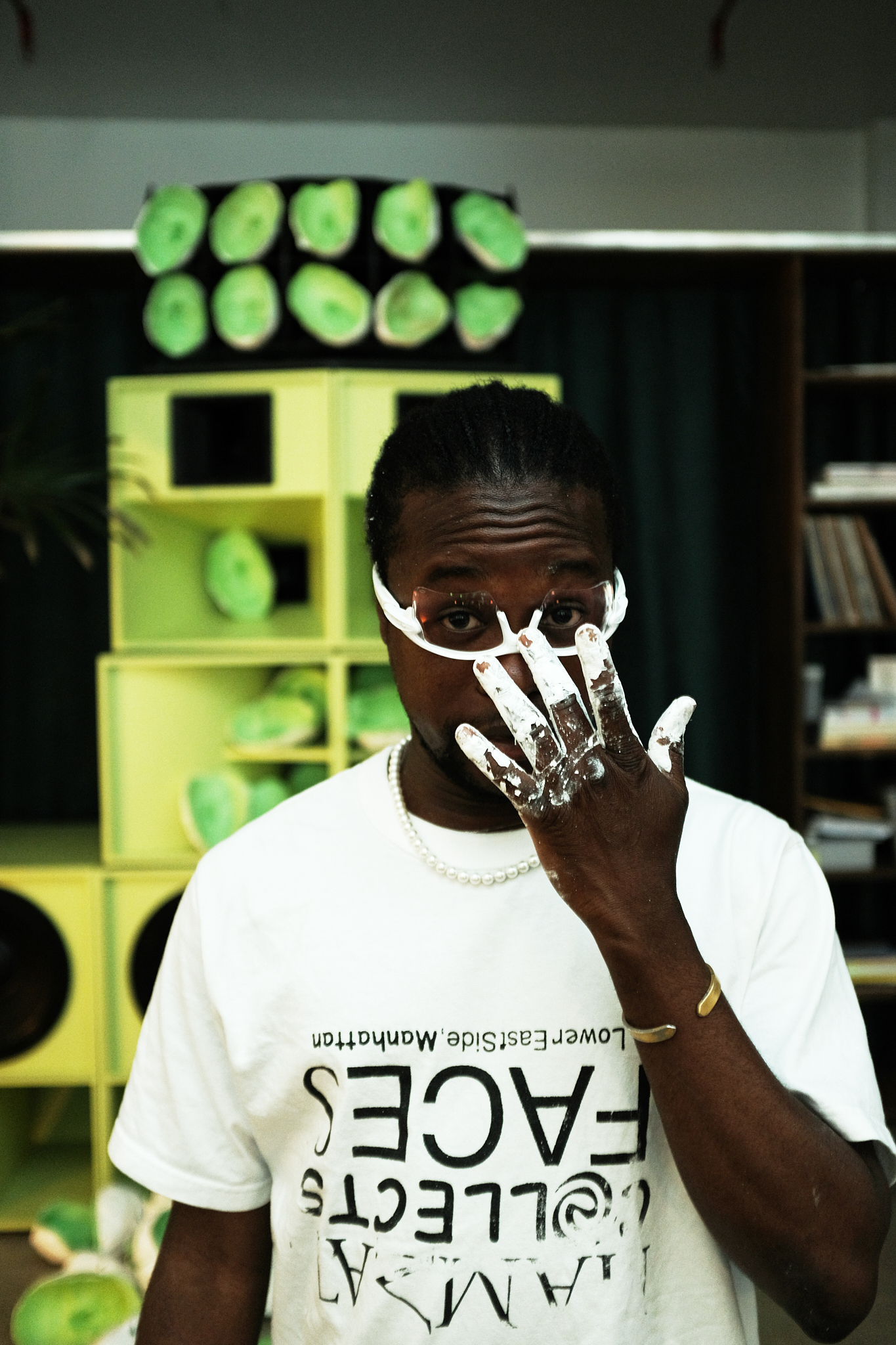

In the middle of May, Raheem prepared for his first sitters of the day in the back of Eternal, an airy creative hub that has been his homebase for the past two weeks. He neatly weighed out his slime-green silicone into rows of shallow plastic cups in the dozens. Buckets of white plaster, swaths of gauze, and wooden paint-stirrers used as applicators were shelved under a rolling cart. He was dressed in all white, “Hamzat Collects Faces” emblazoned upside down on his t-shirt, his signature Oakley sunglasses perched upside-down on his nose. A large lime green speaker setup towered behind him; white masks rested in stacks on every surface.

As he readied for a day that would spill from 4pm late into the night (where blaring music from the newly-opened club below often bumps through the floors), he was calm and thoughtful, an easy conversationalist who bounced between thoughts on artist-collector relations, the latest in robotic science — like the seven axis CNC, a robotic arm used to build cars that he is eyeing — the importance of God and his Muslim faith, and art theory.

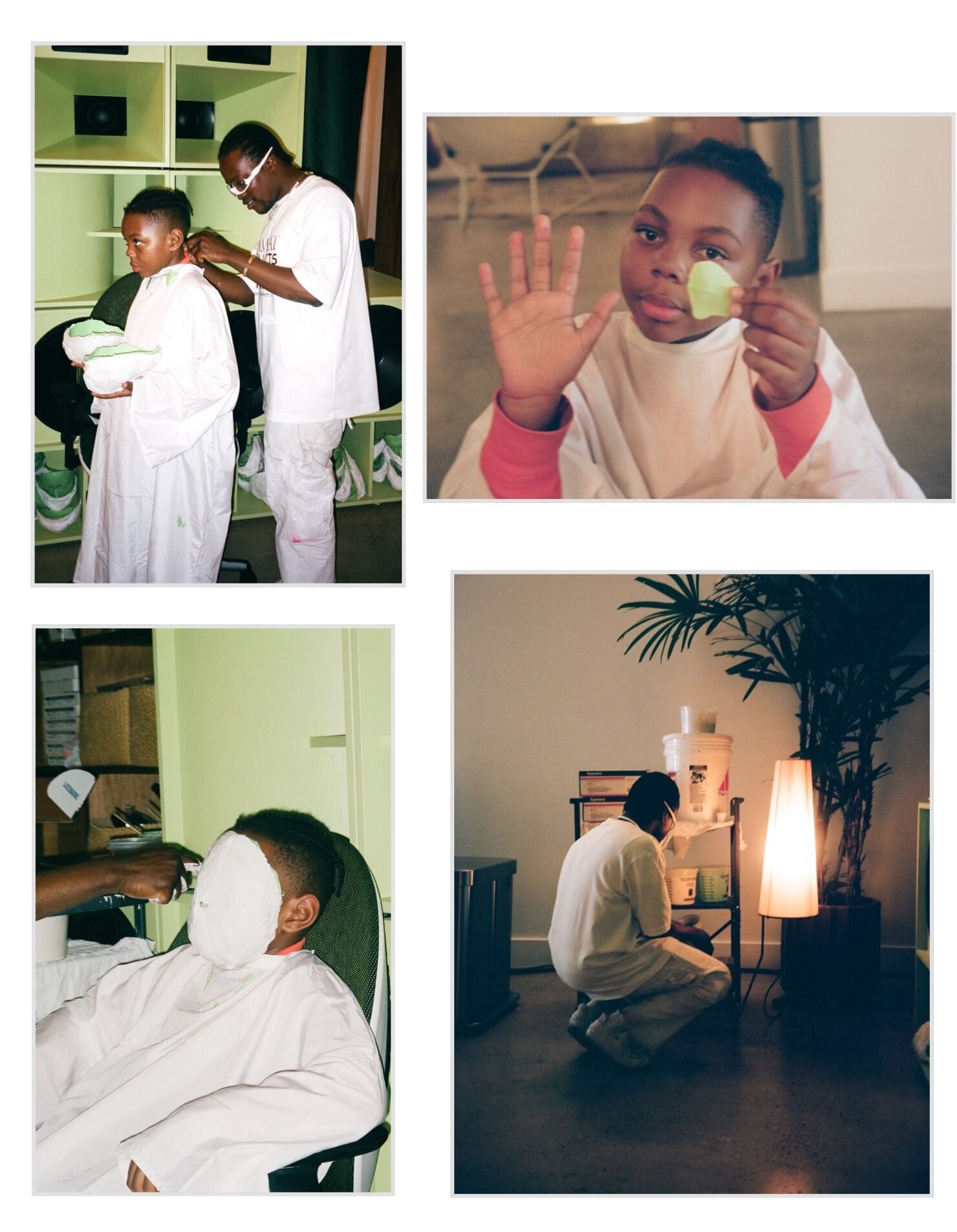

An hour later, Celina Trowell arrived with her son Umoja Trowell, an inquisitive eight-year-old with a politeness at first mistaken for shyness that quickly gave way to enthusiasm. This would be the first time Raheem had collected the face of a child. Before the sculptor began, he huddled together with the duo and outlined the process in plain terms, pausing to make sure Umoja was following. He gently distributed a thick swatch of green goo across Umoja’s palm. This is what it will feel like when it goes on your face, he gestured.

After 15 minutes, he let the boy peel the now solid silicone off his hand. “This is how long it will take to dry.” Umoja gingerly turned the leaf-like piece of rubber over in his hands to examine the fine lines left by the creases of his palm. “I want to make it into a necklace,” he excitedly suggested. Later, Raheem quietly unhooked a chain with Eternal’s spiral logo hanging from it, poked a hole through the mold, and affixed it to the necklace on Umoja as a pendant. After the faces had been collected, Raheem had shared photos of the three smiling, masks in hand, with his own mother. “I see myself in him,” Raheem told Celina, as they looked on at Umoja. He was the same age as the young boy when he arrived in America from Nigeria.

When we meet next, I ask Raheem about the role his subjects play in his practice. As I watched a day of face-collecting, the human interactions were surprisingly moving, and felt like an artwork in-and-of themselves. Raheem nods, “Joseph Beuys has this idea of social sculpture: that society itself can be viewed as the medium to make sculpture; using art you can mold society into whatever you want, potentially something better. Then you have relational aesthetics: art that sees the interactions between people as the work itself. I guess what I’m trying to do is some hybrid between the two.”

At a coffee shop in the midst of the hustle and bustle of midday Chinatown, Raheem traces the origin of his practice back to the first face he ever collected outside of his own: his mother’s. During the process, plaster momentarily blocked her nose and for a few seconds, she couldn’t breathe. Now, Raheem removes the noses of the faces he collects. Is the connection one-to-one? The artist isn’t sure, citing a range of potential reasons as to why he is compelled to alter the faces this way; however, one thing is certain, the otherworldly absence of nostrils has become an integral part of his visual vocabulary. For the artist, removing the nose is what makes it a sculpture.

“Everyday I’m trying to figure out what brought that whimsy into being? Why did I start doing it? It made sense to me at the time,” he muses. The removal of the nose can stir up contradictory notions. The violence of chiseling off the nose is superseded by a sense of unity and togetherness: an alien race of noseless figures that the artist deeply cares about.

The sculptor outlines a complicated and varied history of collecting faces in stone, from the positive (crowning kings and memorialising presidents like Abraham Lincoln) to the negative (scientific racism’s history of using face molds to falsely reinforce racist stereotypes) to the conceptual (Ruth Asawa’s collection of ceramic faces that were discovered in 2022, a year after Raheem began his project). Now, his project offers a new reason for collecting, one that is developing as he goes. When he gets to 500 faces, he will likely have a new perspective, he tells me.

While he was growing up in suburban Massechuettes, Raheem would pretend to be a cyborg with his friends. In high school, a close friend’s family gave him a black MacBook that changed his life forever. “I spent so much time on that computer,” he recalls. “I fell in love for the first time on that computer. I did a lot of graphic design on that computer.” The graphic design led him to getting into Cooper Union’s highly competitive design program before he later changed his major to sculpture. While at Cooper Union, the young artist began to probe mankind’s relationship to technology. “I started to think a lot about what a cyborgian condition might be as opposed to a human condition,” he says of his early work.

He turns his hand over to show me his left fist, which he branded on his 19th birthday. “I come from a culture where it’s forbidden to use your left hand,” he says. “I was thinking of a way to activate my left hand with an intense moment that would force me to pay attention to it and use it more in my practice.”

Then a few years later, in 2019, when Raheem was 23-years-old, studying at an intense two-week-long sculpture program in Florence, the hammer he was using suddenly dropped from his right hand, an icy jolt of electricity rushed through his fingertips. Soon after, he returned home with a two week window before heading to Japan to start his masters at Kyoto Seika University. It was a normal Saturday afternoon home alone at his parents’ house; he was listening to Akon’s “Smack That” and sweeping the kitchen floor when he suddenly collapsed. He lay frozen on his right side before crawling to the living room. A few hours later, his father was rushing him to the hospital where he learned he had had a stroke.

“My dominant hand, my right hand, was so numb that I could barely move it. I was able to use my left hand to support myself in that moment and now beyond that moment,” he says. He left the hospital three days later with a pacemaker permanently installed in his heart and connected to his phone via Bluetooth.

The sculptor marks this as the moment he stopped LARPing as a cyborg and became one. “It stopped being a live action role play; it became my life. It’s a lot less romantic, but it is more real. It has given me an opportunity to think about technology in an intensely neuro-spiritual and deep way,” he reflects.

The family home where Raheem had his cyborgian awakening is now home to his rapidly growing collection of faces. “Massachusetts is where my studio is. That’s what my house is. That’s where my life is,” he says. “Really talented people leave for New York or leave for LA and never come back. Because of that, it is sort of left depleted of its homegrown talent.” He often jokes about being the ambassador of Massachusetts. “I come to New York, I do this thing, and then I get back home. It’s really important for me to return.”

During our conversation, a man ambles over to our table to ask for money. Without missing a beat, Raheem pulls out a bill and hands it to him. At his current stage, he lives art sale to art sale to fund his dream. He understands how money is a necessary means to an end.

In 2023, the trope of the starving artist has lost its romantic edge. It is no secret that the art world is its own industry, but why are artists so often left on the periphery? The expectation of artists to create purely for art’s sake ignores the realities of art-making: the costs of living, materials, studio space, not to mention the often outsized value that is often ascribed to a work after it enters the hands of collectors. “To be honest and put it plainly: I’m an immigrant. I was born into poverty, and I’m not trying to stay in poverty. It’s just not interesting to me,” Raheem says. “I do think that I can create generational wealth with my creativity, and it feels like something I should strive for.”

He notes a shift in culture where artists are reclaiming their profitability. “I have this idea of Hamzat Incorporated.” The early stage artist is akin to an early stage startup, and funding is central, he tells me. “The artist should be prepared to become a business, should be prepared to become incorporated — and also privately traded and publicly traded,” he says, recalling the light-bulb moment when, soon after he graduated, his dad sat him down and told him he needed to start thinking of a business model. The key, he asserts, is setting an intention and establishing a network of support.

His latest face-collecting run in New York was sponsored by like-minded entrepreneurs; Eternal is letting him use its space for free. Two other digital startups aimed at creatives, Arkive and Friends With Benefits, each gave him $250 dollars, and Perfectly Imperfect Newsletter helped him broadcast the events. He sees the future in tech CEOs like Reggie James of Eternal who are artists in their own right or at the very least culturally tapped-in.

There is a zen-like and self-assured quality to Raheem. Even as larger-than-life as his goals might seem (1,000 faces carved with advanced robotic tools in a subterranean area that would need running water and electricity), I get the sense that I am speaking with an artist who has the gift of a combination of willpower and imagination that will make it happen.

The sculptor is optimistic about new technology. He thinks of hardware as sculpture and sculpture as hardware, noting how both iPhones and sculptures contain, and broadcast, information. “I am a deeply religious person,” he emphasizes. “I believe in God as the ultimate, that is my shield against artificial intelligence.”

Words by Meka Boyle