This Artwork Changed My Life is a fortnightly series of personal essays that share the stories of life-changing encounters with art.

I was fixated on glamour long before I had the words to describe it. As a child, I’d spend countless hours drawing girls in riotously colourful outfits. I’d pore over fashion magazines and make collages, anxiously awaiting a time when I’d be an elegant woman with a fabulous wardrobe. By high school, my tiny bedroom was overrun with sketchbooks and my walls were covered with magazine pages depicting well-dressed models and actresses.

The women in these images, made-up and confidently seductive, inevitably appeared to be living their best lives, very much in contrast to me, an angsty teen who had no idea how to properly apply eye makeup, let alone flirt.

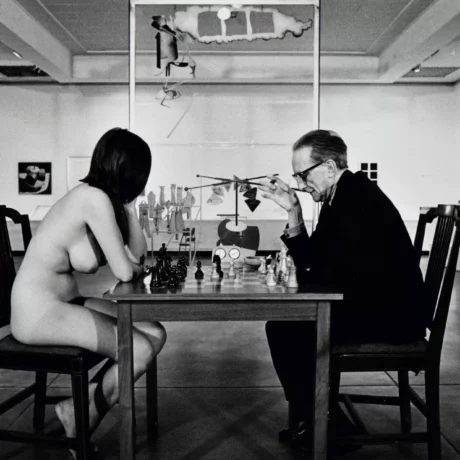

I was paging through an issue of Allure magazine when I first encountered the jaw-droppingly decadent fashion photography of Guy Bourdin. A selection of his extremely 1970s images, including Woman with Portrait of John Travolta, were used to illustrate an article whose subject I’ve long since forgotten. Bourdin’s arresting photograph, however, immediately lodged itself into my psyche.

“The intersection of art and commerce reached its zenith in Bourdin’s imagery”

On the surface, it’s a sexy image: a gorgeous model thrust back over a couch, her legs spread, and one of her garter straps visible. On the fuchsia-carpeted ground sits a framed black-and-white headshot of John Travolta, who was then at his pretty-boy peak. The tableau is both simple and over-the-top, and the more you look at it, the weirder it gets.

The erotic reverie of the shot is simultaneously unnatural (there’s no way that model’s position is comfortable) and elemental (the Travolta image perversely suggests teenybopper fantasy). The colours are downright sumptuous. The model wears a vivid green satin dress tied with a red sash that complements her shiny red heels. It all felt like the height of a nostalgic glamour that I badly wanted to experience as a lonesome high schooler in the aughts.

Bourdin’s career started in the 1950s, but he’s most associated with the photographs he took in the 1970s. Primarily working in the commercial space, his best-known work appeared in French Vogue and ads for footwear designer Charles Jourdan. The image that caught my attention was originally used in one of these ads, and while the model’s richly coloured slingbacks with gold-tipped heels are undeniably chic, they’re hardly the centrepiece.

“It all felt like the height of a nostalgic glamour that I badly wanted to experience as a lonesome high schooler”

The intersection of art and commerce reached its zenith in Bourdin’s imagery. This photograph, which stood powerfully on its own in the decades since it was taken in 1979, was worlds away from the pandering, faux-relatable yet increasingly celebrity-filled media landscape of the 2000s.

In In Between, a coffee table book of Bourdin’s work, Shelly Verthime writes that his photographs create “a dream-like universe, where in between mysterious landscapes and luxurious settings, the viewer is poised on the border of the sublime and the surreal.” When I first discovered Bourdin’s surrealism, social media was just taking off. I felt self-conscious about presenting myself online, and though I loved fashion, I was eternally conflicted about dressing seductively. Bourdin’s photographs were so unlike this world, so heavily stylised and cinematic in their attention to detail, that I couldn’t help but be drawn in.

In the decade-plus since first seeing the image, I’ve written a lot about the sleazy yet stylish, femme fatale-driven world of erotic thrillers, a favourite cinematic genre. When I look at this picture, I see an erotic thriller in miniature.

Bourdin’s aesthetic sits alongside contemporary 1970s photographers like Helmut Newton and Chris von Wangenheim and brings to mind the pouting cover girls of Roxy Music records and campy movies like The Eyes of Laura Mars. It’s easy to level accusations of sexism against Bourdin and the bombastic ‘Me Decade’ imagery he represents but to do so does his wild creativity and mastery of mise-en-scène

a disservice.

“I was drawn to how the image perfectly embodied both glamour and trash, largely because it felt like escapism”

As a teen, I gravitated toward images of womanhood that felt dynamic in a way that I myself did not. In an essay in In Between that compares Bourdin’s work to Alfred Hitchcock and Lewis Carroll, Charlie Scheips writes that the artist “created an art of vivid narrative fantasy suggesting that which had either just happened or was about to happen.” As a teacher’s daughter at a private school who had few friends and fewer romantic prospects, this narrative fantasy thrilled me. I felt like little was happening to me or about to happen.

Though I lived in New York City, my world felt small: I was creative but perhaps not as outwardly adventurous or worldly as one might expect a native New Yorker to be. I was drawn to how the image perfectly embodied both glamour and trash, largely because it felt like escapism.

The subject of Woman with Portrait of John Travolta didn’t look like a helpless victim of the dreaded “male gaze” to me. Rather, she appeared self-assured in a divinely opulent way I hoped to one day channel. Was she waiting for a man to join her, or did one just leave? It didn’t matter. She had her John Travolta headshot and an outfit that paired beautifully with her makeup and the mysterious setting. What more did she need?

“On the surface, it’s a sexy image: a gorgeous model thrust back over a couch, her legs spread, and one of her garter straps visible”

Today, there’s obviously more awareness around sexism in cultural imagery. However, while that awareness is valuable, there’s also a strange tension in how art is expected to avoid provocation, yet women on social media are also expected to constantly be photographing themselves and proclaiming themselves hot as a form of easy empowerment.

There’s little mystery in today’s visual culture. Everything is digital and obvious, and too often moralistic. Bourdin’s work may be edgy but its appeal isn’t rooted solely in sex. His imagery creates a lurid world that’s both inviting and haunting, what Scheips calls a “nostalgic, elegiac embrace of the innocence of youth (or the not so innocent).”

When I first saw the image, I was far more innocent than I wanted to be. I still often feel like I’m failing at femininity in various ways. I find the heightened style and sensual mystique of Woman with Portrait of John Travolta oddly comforting. It’s like a time machine to an archetype of womanhood that’s all the more appealing for being out of reach.

Abbey Bender is a New York-based archivist and writer covering film, fashion, girls, and various forms of nostalgia