Photo by Jack Elliot Edwards

At first glance, Jan Gatewood’s practice is ostensibly devoid of people, populated as it is with cartoonish rabbits, acid-coloured dinosaurs, strawberry-nosed dogs, and septum-pierced geese. Yet its concerns are entirely human, as the title of his first UK solo exhibition at Rose Easton belies. The show is called ‘Group Relations’, after the English psychoanalytic theory designed to unpack bias through the interpersonal dynamics of groups. In Gatewood’s case, it is the coalescence of human behaviour and the factors which influence it, explored in the context of race and identity– and in which the human figure is seemingly overshadowed by its bestial counterpart.

Gatewood tells me that “in-group relations theory, the goal of the practice is a ‘conference’; a group discussion”. The artist’s primary reference is a 2020 artwork by the performance artist Andrea Fraser, titled This meeting is being recorded. In it, Fraser assembles an intergenerational group of white women, examining unconscious racism and their roles in white supremacy. Gatewood has transposed the technique to a body of work investigating representations of race within visual art itself; he sums up his desired response to his work as “a group discussion of the responsibilities of people who choose to capitalise on depictions of their race via identity-based figurative painting”.

Photo by Jack Elliot Edwards

Discussion is debate and, therefore, critique; this lies at the centre of the artist’s practice, which is simultaneously critical of representation, aesthetics, language and the art industry. Fraser argues that to be critical requires empathy, and it reminds me of one of Gatewood’s Instagram captions, which talks of “empathetic action”. Empathy has been on my mind a lot recently. I have a short essay screenshotted on my phone by the writer Estelle Hoy, which I keep coming back to. “Where is our universal empathy (?!)?”, she writes, “our collective, vital pursuit of good and closeness that tames the total madness of delusory differentiation– a monstrous cadence that exactly resembles defeat”. Empathy– now, as it has always been– is urgent.

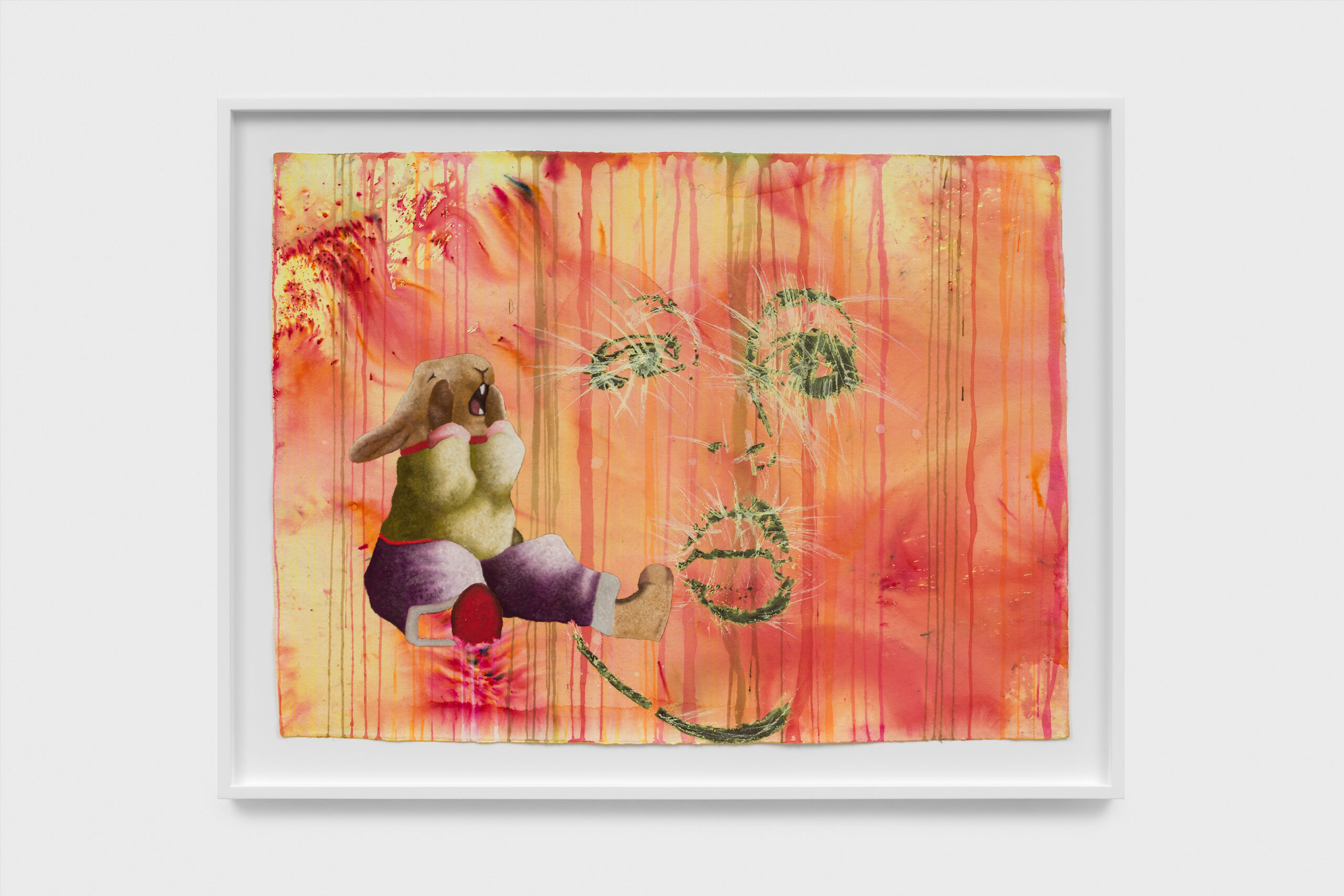

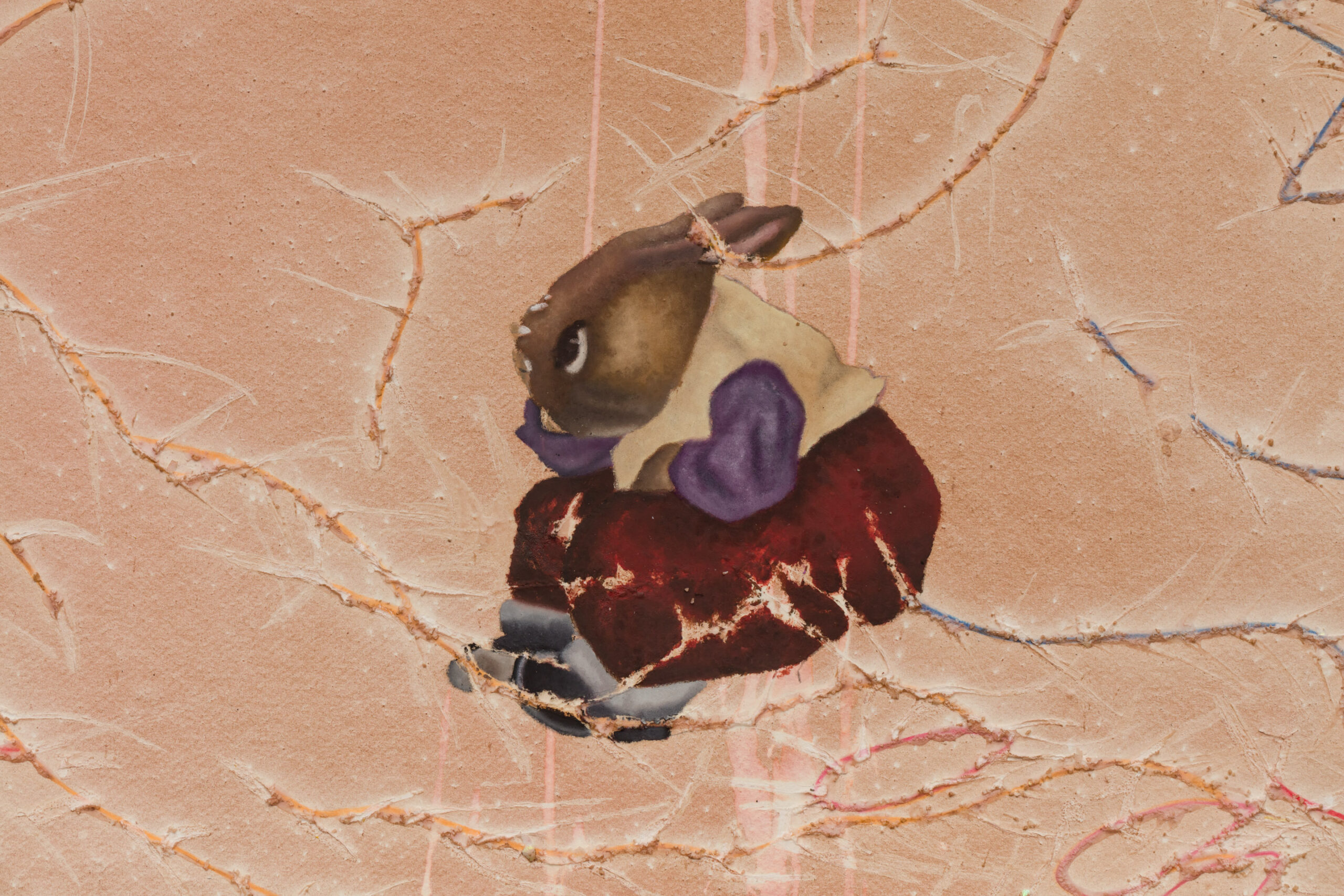

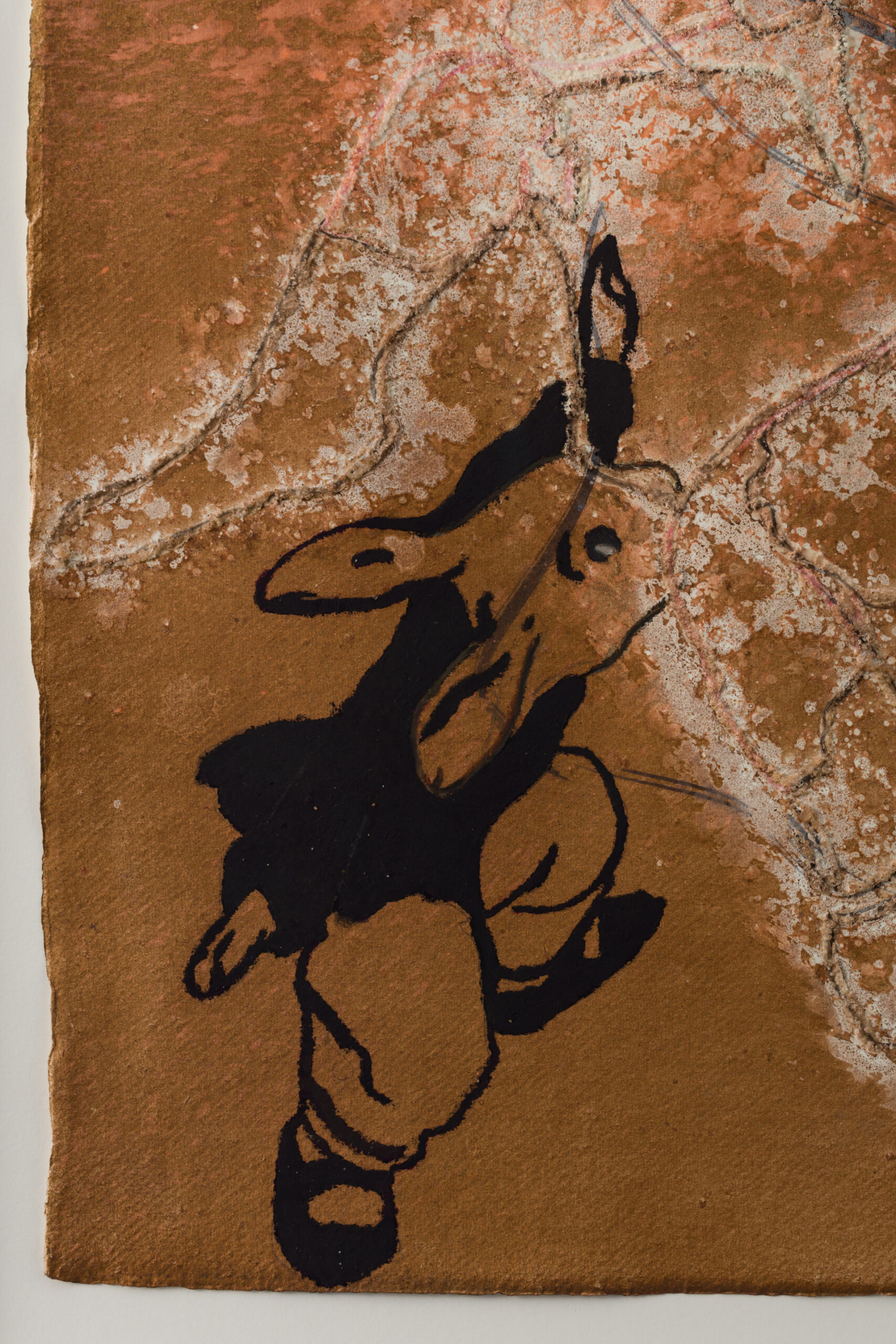

In the context of Gatewood’s work, empathy is “directly placing myself within the subject matter that I’m critiquing”. In this case, the aforementioned subject matter is the commodification of Black representation, and the artist’s empathetic vehicle of choice is the rabbit. “Early on, I knew I didn’t want any human figures in my drawing practice”, he tells me. “I was weary of identity politics outweighing my material and conceptual concerns”. In ‘Group Relations’, the rabbit appears entangled in the limbs of reclining figures or embedded in scenes of intimacy, nimbly dodging (with its renowned agility) what might otherwise be considered obscene.

The character is also entwined with Black American storytelling. The rabbits in Gatewood’s drawings nod distinctly to Br’er Rabbit, a folkloric trickster who originated in the oral stories of enslaved African Americans in the Southern United States and the Caribbean. “Br’er Rabbit uses wit and humour to achieve what he views as successes, and oftentimes I think as an artist, that’s what I’m doing”, he explains. Humour, after all, is a great catalyst for connection (empathy). Gatewood calls it a “sugar in the medicine” approach.

Photo by Jack Elliot Edwards

Photo by Jack Elliot Edwards

Much of the artist’s sensibilities are rooted in the idea of what he describes as “finding alternatives”: alternative subjects, alternative materials, and alternative methods of education. Although he forewent a formal art education in favour of YouTube tutorials and kitchen table canvases, having only concretely decided to become an artist at the age of 22, Gatewood resists the ‘self-taught’ narrative; “I’m weary of the way that kind of categorisation contextualises an artist and their practice”. Instead, he sees his background almost as a continuation (or predecessor) to his rule-bending practice. “The art world is a space where I saw the importance of relationships and how that could affect one’s opportunities”, he tells me. “I was and still am more interested in experimenting with renegotiating norms rather than viewing my alternative point of entry as a hindrance”.

Gatewood’s earliest experimentations with art, formed in his days as part of LA’s skateboarding scene, were in the form of collages– a technique which still somewhat informs his current practice. The rabbits of ‘Group Relations’ sit amongst references from Bamboozled to Gone With the Wind; the art of David Hammons to that of Merlin Carpenter. Complications of a fragmented self (2023), its title ambiguous yet enigmatic, depicts the word ‘Beloved’ in a nod to the late author Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, Beloved (1987). Willingness to try (2023) is a similar paper work, the phrase ‘REARRANGE the self AS AN ACT of humility’ cross-hatched into its flushed surface like scars upon pink flesh. “I like how decisive you have to be when using text in visual art”, says Gatewood. “I like how the work can change, and the images can change based upon their pairing with language. It goes back to my collage impulses: to mash things together which might not have initially combined easily, to form something new”.

(Henry Taylor at Manuela, Los Angeles), 2023 (detail) Courtesy of the artist and Rose Easton, London

Photo by Jack Elliot Edwards

Mashing things together which don’t combine easily… in other words, things which resist each other. This idea appears again in Gatewood’s material choices; the paper drawings of ‘Group Relations’ are coloured by fabric dye– a water-based medium– then scratched, bleached and layered with glue, which resists the dye but binds with the paper, and other materials like salt, and lemon juice. The artist has been lauded for his use of quotidian materials, but their unconventional nature does not overshadow the conceptual concerns underlining them. Glue, like humans, is formed of bonds, which simultaneously encounter and overcome difference (resistance).

Yet since Gatewood’s practice, in its concern with the implications of figuration, is involved with criticism of the visual art industry itself, it seems inevitable to ask: how do you resist that which you are inextricably involved with? Selling works commercially is an inevitable route, but relies on the art world’s notorious exclusivity. Gatewood’s solution is free artworks, given away alongside each exhibition he holds, such as the selfie-printed posters of the past or the black lace trimmed cushions of ‘Group Relations’. The fact that a lot of these free works have featured the artist’s face is a continuation of the discourse surrounding the commodification of representation, which underscores his work. “I decided early on I would distribute my image on my own terms”, he tells me. So it is through figuration– or a lack thereof– that Gatewood explores his theme: how we relate to each other within the framework of race. It is as much about criticism as it is about empathy. If the rabbit is able to become an instrument for connection, how is it that empathy between humans seems so scarce? Where is that “universal empathy” that Hoy talks about? Through his work, comprising everything from theory to popular imagery, Gatewood questions the role which visual art has to play in all of this: its role– quite literally– in ‘Group Relations’.

Written by Ella Slater